A Piece of the Pie: How Common But Differentiated Responsibility Assigns Countries Their Fair Share in the Fight Against Climate Change

By Michella Oré

Michella, Class of 2016, is a Political Science major (concentration in International Relations)

Nearly 25 years ago, leaders from around the world traveled to Brazil to discuss climate change and how each country could do its part to fight it. The 1992 Rio Earth Summit took place over several days, during which an international treaty was negotiated to address through the stabilization of greenhouse gas emissions. Modeled after the Montreal Protocol, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) laid out the criteria necessary for regulating emissions of these hazardous gases. The UNFCCC was signed on June 4, 1992 and entered into force on March 21, 1994.

The UNFCCC made use of several concepts, including adaptation and implementation, which explained in detail the actions to be taken upon by countries when they signed onto the treaty. The concept that this post will focus on is common but differentiated responsibility (CBDR). CBDR appealed to me because it is one of the few concepts introduced in the UNFCCC that both acknowledges the historical past of all countries and assigns them relatively fair portions of responsibility based off these histories. This assessment should prove useful in the current negotiations taking place at this year’s Conference on Climate Change (COP21) because it lays the foundations for an equitable arrangement, which ideally will increase the incentives for countries to speed up their responses to the issue of climate change. For this post, I will explore the development of CBDR and its effectiveness in reducing greenhouse gas emissions on a global scale.

Introducing Common But Differentiated Responsibility (CBDR)

CBDR refers to the expectation that countries, both developed and developing, will bear responsibility proportional to their resources and capabilities in the “international pursuit of sustainable development” (Vanderheider 2015). It was based off the “common heritage of mankind,” a concept that understands humanity as sharing several resources. Under the common heritage of mankind, these shared resources are to be preserved and taken care of by all countries since they are seen as benefiting from what they offer (Harris 1999). Climate change was eventually added to this list of shared resources generating the understanding that it is every nation’s responsibility to stabilize their greenhouse emissions as they effect the climate which impacts all inhabitants on earth.

Within the UNFCCC countries considered “developed” are assigned greater responsibility, in addition to being legally bound to the treaty, while those considered “developing” are expected to contribute less and are not legally bound to do so. The need for a concept that “differentiated” responsibility arose from the understanding that developed and developing countries do not have equal technologies and financial resources and that it would be unfair for a developing country to contribute as much as one that is developed. Principle 7 of the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development echoes this sentiment, by stating that developed countries “acknowledge the responsibility that they bear in the international pursuit to sustainable development in view of the pressures their societies place on the global environment and of the technologies and financial resources they command” (Harris 1999). The concept of CBDR brings to light an important point, that developed countries will be able to not only lead the way in finding more sustainable ways of living as a global community, but that they will be able to actually support these initiatives because of their wealth and status in the international order.

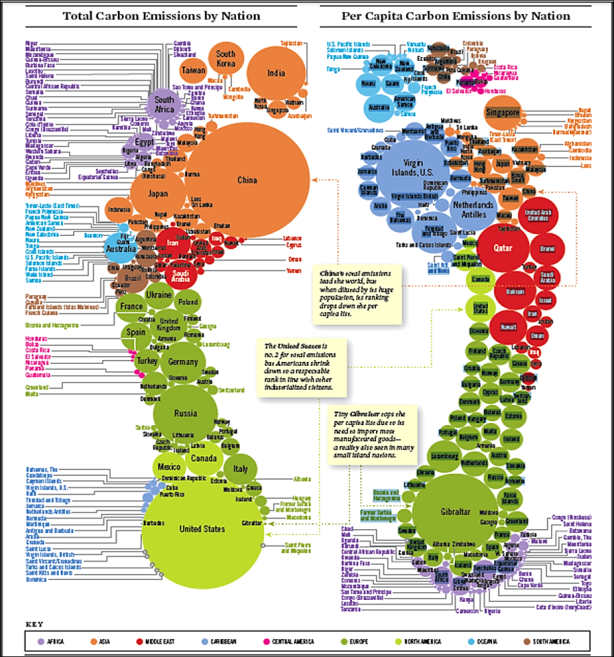

CBDR also highlights the importance of leveling the playing field–the countries that are considered to carry more of the responsibility for acting on climate change are countries that have historically emitted more greenhouse gases. In Essential Concepts of Global Environmental Governance by Jean-Frederic Morin and Amandine Orsini, this idea of “historical responsibility” goes back to the beginning of industrialization and assigns greater responsibility to those countries who were amongst the first industrialized nations, like the United States and Great Britain (Vanderheider 2015). These early industrializers are seen as some of the biggest culprits in high emissions of greenhouse gases because they industrialized at a time when omitting these gases were less regulated. However, even proof of early emission has not made developed countries more inclined to shoulder a larger share of the responsibility in reducing gas emissions. One of the arguments against historical responsibility is that early industrializing countries do not feel they should be held responsible for their actions in the past since little was known about the harmful effects industrialization would have on the climate in the future.

Another argument follows that countries that are considered developing, like China, have actually been amongst the biggest emitters of greenhouse gases since the establishment of the UNFCCC but, because the treaty does not require developing countries to adapt measures to lower their emission levels, they are getting away with less than their fare share of responsibility. While the U.S. does not believe it should be held accountable for its earlier emissions, it does support mandating emission targets for rapidly developing countries. Their support for these targets was created in response to the emission trends over the past twenty years: “In 1990, developing countries produced one-third of annual global emissions; today they emit 55 percent of them. Projections indicate that by 2030, developing countries could produce as much as 70 percent of global emissions” (Cameron 2012). These differing interpretations, particularly over who should carry more responsibility, lead one to wonder how effective CBDR has truly been.

Are We Closer to Our Goal? CBDR’s Effectiveness in the Fight Against Climate Change

Mary J. Bortscheller argues that CBDR has actually worked to undermine the effectiveness of the UNFCCC, because of its outdated assessment of what should be required of developing countries. She explains that under the treaty developing countries are not required to implement initiatives that will lower their emission levels, meaning their adherence to the current framework of the UNFCCC does not guarantee that countries like China will actually adapt stricter regulations. Bortscheller concludes that “any climate change agreement that excludes China and other emerging economies from emission reduction targets will not have practical utility because these countries’ rates of emissions are increasing rapidly” (Bortscheller 2010). In other words, no effective fight towards climate change can take place if the countries that emit the largest portions of these gases are not assigned a greater responsibility to lower their levels, regardless if they are considered developed or developing.

In recent years there has been a shift towards creating a more equitable and relevant concept beyond CBDR. One such concept is “equitable access to sustainable development,” which was first introduced in the Cancun Agreements, a list of decisions reached at the Climate Change Convention in 2010. The Agreements represented an understanding by the parties involved that the priorities of developing countries are “social and economic development and the eradication of poverty,” and that in order to have global participation in the fight against climate change the initiatives created going forward must empower developing countries to choose how they go forth with sustainable development (UNFCCC). Another concept is an extension of CBDR: “common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities, in light of different national circumstances” (Climate Nexus 2015). Again, this phrase acknowledges that countries, depending on whether they are developed or not, will have different priorities. While the fight against climate change is a global initiative, it is just as important for countries to consider how they will tackle this issue on a local level as well.

How will local initiatives differ between developed and developing countries? Marcus Hedahl writes that the difference will be between focusing on the economy versus improvement of civilian life: “In the developed world, they will be done as part of the normal recapitalisation of infrastructure. In the developing world, they will often by done as part of a larger effort aimed at development and alleviation of poverty” (Hedahl 2013). Where countries focus their efforts will depend on what is crucial to their personal needs. Once countries tackle their issues on a local level they will be better equipped to put forth viable initiatives in the fight against climate change. The shift in creating concepts beyond CBDR points out that while the concept of CBDR alone might been more effective in theory than in practice, re-evaluating it in a more relevant context will only help to ensure that it serves its intended purpose—enlisting all countries in the fight against climate change to create a better environment for today and tomorrow.

Conclusion

It is incredibly important for countries to not dismiss the past when assessing the future because these things are not mutually exclusive. CBDR is a concept that reminds nations to not forget this crucial point. Its intended goal is to protect countries from bearing an unequal amount of responsibility, when they have either not participated in the problem or only did so to reap the benefits of an industrialized, international community. However, the concept is not without its flaws. We cannot only take the past into account when developing initiatives to fight against climate change, we should also look to the present and future. For this reason, responsibilities assigned to countries should based on their historical role, equity-per capita emissions, and their capacity to implement change. This would ensure that rapidly developing countries are not let off the hook but are instead forced to take on their fair share in creating a sustainable living environment for tomorrow.

Bibliography

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). 1992. “United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.” Opened for signature at Rio de Janeiro 4 June; in force March 21, 1994.

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). 1992. “Report on the workshop on equitable access to sustainable development.” Opened for signature at Rio de Janeiro 4 June; in force March 21, 1994.

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). 1992. “The Cancun Agreements.” Opened for signature at Rio de Janeiro 4 June; in force March 21, 1994.

Vanderheider, Steve 2015.”Common But Differentiated Responsibility.” In Essential Concepts of Global Environmental Governance, ed. by Jean-Frederic Morin and Amandine Orsini, 31-34. Routledge.

Harris, Paul G.1999. “Common But Differentiated Responsibility: The Kyoto Protocol and United States Policy.” New York University Environmental Law Journal. 7(1): 27-48. http://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/nyuev7&div=8&g_sent=1&collection=journals.

Biermann, Frank. 2010. Global Climate Governance beyond 2012: Architecture, Agency and Adaptation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bortscheller, Mary J. 2010. “ Equitable But Ineffective: How The Principle Of Common But Differentiated Responsibilities Hobbles The Global Fight Against Climate Change.” Climate Law Reporter. 10(2): 49-68. http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1036&context=sdlp.

Hedahl, Marcus. 2013. “Moving from the principle of ‘common but differentiated responsibility’ to ‘equitable access to sustainable development’ will aid international climate change negotiations.” The London School of Economics and Political Science Blog. http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2013/09/28/moving-from-the-principle-of-common-but-differentiated-responsibility-to-equitable-access-to-sustainable-development-will-aid-international-climate-change-negotiati/

Cameron, Edward. 2012. “What Is Equity in the Context of Climate Negotiations?” World Resources Institute Blog. http://www.wri.org/blog/2012/12/what-equity-context-climate-negotiations

Das, Ishita. 2015. “The Road from Rio to Paris: The Evolution of CBDR?” Oval Observer Foundation. http://ovalobserver.org/road-rio-paris-evolution-cbdr/

Climate Nexus. 2015. “Common but Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities (CBDR-RC).” The Road Through Paris. http://www.theroadthroughparis.org/negotiation-issues/common-differentiated-responsibilities-and-respective-capabilities-cbdr–rc