By Mona Sami, Astrophysics and Economics major, Class of 2016

With the effects of global climate change now more obvious than ever, the stakes going into the UNFCCC COP21 Conference are at an all-time high. The previous climate summit of this scale, the 2009 Copenhagen Summit, ended in failure and many steps have been taken to ensure a more successful fate for COP21 in producing a global climate change agreement. Leaders met in Bonn in October to continue to develop a draft text for the conference. The hope is that this draft text will expedite the negotiation process by acting as a base for the negotiations. To supplement the draft text, countries have been encouraged to submit their own Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs). These INDCs are an opportunity for countries to present their mitigation goals in the context of their own abilities and unique circumstances.

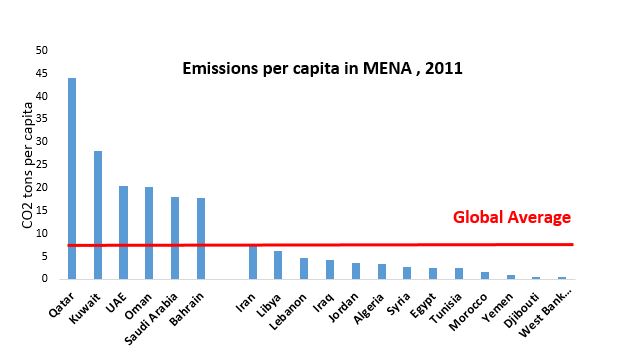

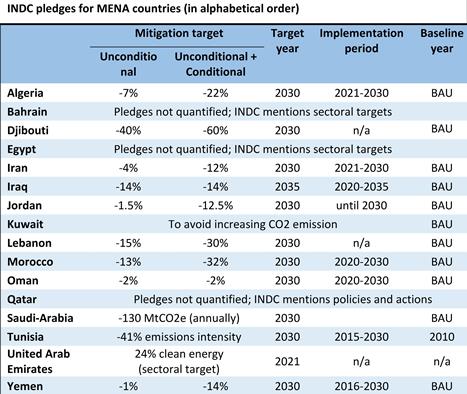

As of the start of COP21, 156 INDCs have been submitted representing 183 countries. Notably late to submit their INDCs, however, was virtually all of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) nations and many other non-OPEC petroleum exporting countries in the Middle East and North Africa. The only such nation to meet the October 1st INDC submission deadline was Algeria, with Oman and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) submitting their INDCs on October 19th and 22nd respectively. In the few weeks leading up to COP21 Saudi Arabia, Iran, Iraq, Qatar, and Kuwait made last minute submissions of their INDCs. At the time of these submissions over 160 countries had already committed to INDCs, making the regional concentration of these late submissions especially alarming.

Why Were Petroleum-Exporting Countries So Late to Submit INDCs?

Some have argued that the turmoil in many of these countries is the reason they were late to submit their INDCs. This is a weak argument, however, as countries considered more fragile or of comparable fragility as determined by the Fragile State Index submitted their INDCs well before the start of COP21. Another argument, made by OPEC Secretary General Abdalla Salem El-Badri, is that the OPEC countries were reluctant to commit to climate action because they feel doing so jeopardizes their poverty reduction and development efforts. This is, again, a weak argument. OPEC countries such as Saudi Arabia and Qatar have some of the highest levels of gross domestic product (GDP) per capita but submitted their INDCs just days before COP21 while countries with much lower levels of GDP per capita and UN Human Development Index scores have submitted theirs, again, much earlier.

The fear is that many of the petroleum exporting countries may instead be trying to undermine the international climate negotiations. With economies that are highly dependent on the sale of fossil fuels, their interest in preventing the success of climate negotiations is obvious. A successful climate negotiation would mean a phasing out of fossil fuels and thus would spell out disaster for hydrocarbon dependent economies. There are many signs that point to the efforts of these countries to prevent the success of COP21. In October Secretary of State John Kerry went to Saudi Arabia to meet with King Salman to discuss a host of issues including the upcoming Paris Conference. The press release by the Department of State after the meeting stated that they, “…pledged to work together in advance of the upcoming COP 21 climate conference in Paris” (US Department of State, 2015). In contrast, the press release by the Saudi Press Agency merely mentioned that they discussed, “..a number of issues of mutual concern” (Saudi Press Agency, 2015), making no specific mention of talks of climate change action. Many fear that Saudi Arabia, being such a large player in the region, is trying to secretly make arguments against climate action that appeal to other petroleum-exporting countries in an effort to increase the division going into the climate talks. The more affluent Persian Gulf states of Qatar and the UAE appear to actually be committed to climate action, not swayed by the Saudis’ efforts, but they have little political power in influencing the other nations in the region.

The fact that these countries even submitted INDCs at all came as a surprise to many negotiators. There are several reasons that have been presented for what may have spurred these countries to finally act. The first is supported by the fact that most of the INDCs from the region were submitted well after INDCs from the rest of the world. There is some speculation that these countries were so late to submit INDCs because, initially, they did not plan to do so at all. Then, once they saw that many of the INDCs of other countries indicate a continued reliance on fossil fuels, they felt less victimized by climate action and thus were more willing to commit to the efforts. The second possible reason is supported by the content of the submitted INDCs of the region. Countries in the Middle East and North Africa are particularly vulnerable to many of the effects of climate change due to their extremely arid climates. Given that many of the INDCs of these countries highlight this vulnerability, it is reasonable to assume that this may be what has led them to eventually submit their contributions.

Analysis of Submitted INDCs by Relevant Countries

The World Resource Institute identifies three characteristics that make an INDC “good.” The INDC must be ambitious, transparent and equitable. An ambitious INDC ensures that the climate mitigation goal of keeping global warming below 2oC is achievable. INDCs must be transparent in order to have an effective mechanism by which the progress towards the stated goals can be tracked and they must also be equitable so that each nation is doing their fair share towards the goals of climate mitigation and adaption.

In their INDC, the only concrete mitigation commitment Oman makes is to controlling greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions growth to 2% below business as usual (BAU) starting in 2020. They also commit to efforts on adaption to climate change conditional on the receipt of international funds from the UNFCC, again, with no specific commitments. This INDC fails to be fully ambitious, transparent or equitable. With a GDP per capita of over $19,000 Oman is ranked 31 globally. Given their means, they should be able to set more ambitious targets even without financial assistance from the UNFCC. Also, their lack of any specific targets or commitments beyond the 2% below BAU number renders their commitment difficult to enforce and thus not very transparent. Additionally, for a country of only about 3.4 million people, they are the 55th largest emitter of carbon dioxide. Thus, in order to be equitable, they should be taking on a larger portion of global GHG emissions reductions. For example, Morocco, a country with comparable emissions and a much lower GDP per capita, commits to a reduction of 12% below BAU. Comparing this to Oman’s 2% figure highlights the need for Oman’s commitments to be more equitable.

Kuwait’s INDC is a bit better by the WRI’s standards. In it they pledge to decrease emissions below business as usual. They set out a plan for doing so by first breaking down the contributions by different industries to GHG emissions. As expected, the energy industry is the biggest contributor at 95.3% of total emissions. Thus, their plan to reduce emissions focuses mostly on the energy industry. They indicate that they plan to reduce energy subsidies as well as enact various clean energy programs to hopefully reach their goal on an entirely voluntary basis. Given the detailed plan of action they present to reduce emissions Kuwait’s INDC is very transparent. Also, in many points in the INDC Kuwait points to specific ways in which the country has been affected by climate change so it seems they are attempting to be ambitious as they deal with these issues. It is difficult to say, however, whether this INDC is equitable. Kuwait focuses a lot on how climate change has affected their country specifically so it is hard to tell whether they are addressing the issue in a way that will only be as extensive as necessary to mitigate the effects on their own country or if they plan to act in a way that will be equitable given their global share of GHG emissions. And, if they do only plan to act as much as is necessary to fix the problem in their own country, will this possibly be enough to have the positive co-benefit of also leading to climate action that is equitable on a global scale?

In their INDC, Iran outlines two possible courses of action. These are the “conditional” and “unconditional” options. The “unconditional” option outlines what Iran commits to do given the current circumstances. They present a plan to reduce GHG emissions to 4% below BAU by 2030. The “conditional” option outlines the additional action Iran will take if the international community agrees to remove all current sanctions and not subject them to any more in the future. Here, they outline a plan to reduce emissions even further to 12% below BAU in the same time frame. This 12% number is relatively low given their status as a high GHG emitting country. They are the 12th largest GHG emitter in the world so in order to be equitable they should be taking on a larger share of emissions reductions. It is also not a very ambitious target given their means. Even an oil producing country like Algeria, with a GDP half of that of Iran, has committed to a possible 22% reduction in GHG emissions below BAU. The INDC is, however, transparent. Iran outlines what they plan to do to reduce emissions as well as what resources they will need to do so. This gives the international community very valuable information on what aid Iran will need to reach its mitigation goals.

In their INDC Qatar restates their prior commitments to diversify their economy away from hydrocarbon industries. They then outline some steps they have taken to do so such as implementing programs to increase energy efficiency, and investment in research and education. They note that they would need substantial technology transfer in order to transition to clean energy sources given the harsh climate of the country. The discussion of mitigation does not go much beyond this outline of measures currently in place to improve economic diversification in the country; they do not give any concrete emission reduction goals or future plans of action. This makes their INDC anything but transparent. To make things even worse, they state that they will not take any climate action that would have a harmful effect on their oil-dependent economy. Thus, it seems that any possible ambitious or equitable action Qatar could take has been ruled out.

Similarly, the INDC of Saudi Arabia also highlights their dependence on oil. They describe two possible scenarios for the country going forward. The first is one in which revenues from oil exports are used to diversify their economy away from commodities such as oil and towards more value added sectors such as financial services and renewable energy. Under the second scenario, Saudi Arabia plans to “sustainably” use oil and gas to industrialize their country. They plan to develop their baseline for emissions reductions based on some combination of these two scenarios. This would imply that they plan to continue to use a high volume of fossil fuels going forward. The INDC then highlights several ways in which their plan for diversification will have co-benefits for mitigation. It seems that Saudi Arabia does not plan to directly pursue mitigation efforts; rather, they are only presenting the mitigation related by-products of their economic goal of diversification. This renders their plan inequitable as they clearly do not plan to take on any action beyond what will occur as a result of their diversification efforts. They are not at all considering their global share of emissions in their mitigation plans. By presenting detailed descriptions of each of the mitigation co-benefits of their diversification efforts, however, Saudi Arabia does provide some transparency in their INDC. Additionally, the INDC does seem somewhat ambitious. As they stress in their INDC, given the investment necessary to diversify an economy so dependent on fossil fuel exports away from such exports, they will be required to invest a large sum of money into diversification efforts moving forward pending the rest of the world starts reducing fossil fuel consumption. This large investment will then, as stated above, have many mitigation co-benefits. Given their status as the richest country in the region as measured by annual GDP, though, they could be even more ambitious by agreeing to contribute to global research and development into clean energy, even given their firm reluctant to reduce hydrocarbon use directly.

In contrast to this, the INDC of The UAE meets all three of the criteria described by the World Resource Institute. They acknowledge their dependence on hydrocarbon production but then also lay out a detailed plan for how they will reduce emissions and increase efficiency in their production of hydrocarbons as well as in many other aspects of their economy. Although they give no specific GHG reduction targets, by describing in detail their specific plan of action for mitigation the UAE has made their INDC transparent. The INDC presents plans to improve everything from GHG emissions in the transport sector to food security and public training and education programs. This makes it both ambitious and equitable. The UAE is the 27th largest emitter of carbon dioxide and thus it needs to have a mitigation plan as ambitious and exhaustive as the one it has presented in order to be equitable. The UAE has always been a leader in the region on climate issues and it seems they are continuing that trend in their INDC.

Like the UAE, Algeria also submitted a plan that meets the criteria for a good INDC. They detail a plan to reduce GHG emissions by a minimum of 7% and as much as 22% pending the receipt of international assistance. The mitigation measures they set out are comprehensive in content and in scope, making their INDC both transparent and ambitious. They are also a low GHG emitting country in per capita terms, ranked 36th worldwide in carbon dioxide emissions but with a population of almost 40 million people. By contrast, Canada, with a population of just under 36 million people is ranked 12th worldwide in carbon dioxide emissions. Given their mitigation goals, it seems that Algeria’s INDC is equitable as well.

The INDC of Iraq was developed with the support of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Conditional on international help, they plan to reduce emissions by 15% below BAU. They discuss climate mitigation measures already in place as well as the need for international support and increased internal stability to take any more aggressive action. Given the unique state of the country, this is a fair condition for them to have. The political turmoil in the country prevents them from being able to currently take the steps necessary to reduce emissions but the fact that they are committing to action pending help on improving these conditions makes this INDC both equitable and transparent. Additionally, the fact that they even make any commitments given their current state shows they are being as ambitious as possible in setting their goals.

Non-INDC commitments

Many of these countries have also made some non-INDC commitments to climate change mitigation through domestic legislation and policies. Saudi Arabia established the King Abdullah City for Atomic and Renewable Energy by Royal Order in 2010. The goal was to create a sustainable city in which scientists could conduct research on renewable energies to be integrated into Saudi Arabia’s future energy mix.

Another country to introduce non-INDC commitments is Iran. They have various legislations in place to encourage the private sector to seek out renewable energy options, most notably their Fifth Five Year National Development Plan (FYDP). The FYDP sets out to accomplish this through the use of subsidies and other measures intended to influence consumer behavior. While these legislations prove these countries are at least somewhat committed to climate change mitigation, their commitment to the success of the Paris Conference is hard to determine when they still have yet to submit their INDCs.

Given their reluctance initial reluctance to commit to the success of the Paris Conference, many other countries fear these petroleum-exporters may be trying to undermine, or at best dilute, the climate negotiations. Although some states such as the UAE and Algeria do seem truly committed to climate change action, the support from the region as a whole is hard to gauge given many of the vague and non-ambitious INDCs. Looking forward, it will be interesting to see how these countries engage at COP21.