Unlike the veteran archaeologists making their mark on Omrit for the second time, I and the other first-timers have learned very quickly that we signed up for a difficult job. At the end of each day, I change out of my dirt-covered pants, wash the dust and dead gnats off my face and arms, and rest my aching lower back on my (suddenly luxurious) twin bed. Lying in silence, I’m full of a sense of accomplishment and a yearning to continue with the important work I’m doing in the field. Still, as rewarding as this experience is, even a seasoned archaeologist would admit the need for some downtime to alleviate the physical stress of a dig.

For this reason, Professor Rubin and our other fearless leaders pack our weekends with activities. Since the trip is meant to be an educational experience, our weekend activities typically consist of excursions to places of historical, archaeological, religious, or cultural importance.

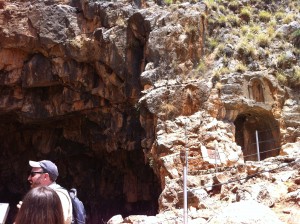

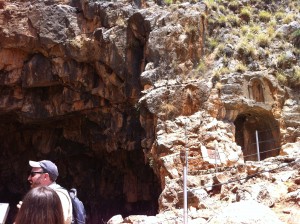

This past weekend, we visited several sites relatively close to home—our temporary home, that is. On Saturday, we worked at the site from 5 to 8:30 AM (!), came back to the kibbutz, ate breakfast, and made our way to Banias. This site, located in the Golan Heights just northeast of Omrit, is associated with the Greek god Pan (for whom it is named). Here, one can find a cave dedicated to Pan as well as several niches in the adjacent cliff face in which statues of deities would likely be located. Near to this site is a temple and larger city erected by Herod the Great. We walked through these sites while Professor Rubin and Professor Jason Schlude of Duquesne University gave short lectures about the history of Banias. After the guided tour, some students and I made our way to Banias Falls, which, according to an unnamed Carthage College student, is the highest waterfall in the Middle East. Regardless of its relative height, the falls were beautiful and entirely worth the trek.

Prof. Rubin in front of Pan’s cave. Crazy to think a creature once revered as a god is now representing the Israel Nature and Parks Authority. Oh! how the mighty have fallen.

How the mighty have fallen, indeed.

On Sunday, we made our first trip of the season to another active archaeological site, Huqoq. Under the direction of Professor Jodi Magness, the excavators at Huqoq are making great strides at revealing the remains of a late Roman synagogue notable for its largely intact mosaic of the Biblical character Samson. Prof. Magness spoke electrically about her site, and we relished the opportunity to see how other students and professors work at a different location.

Unfortunately, I couldn’t take any pictures of Huqoq since their finds have yet to be published. Instead, here’s how the Israeli Parks Authority warns people against drowning.

Later in the day, we made our way to Tiberias, a modern city on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee. Though we were eager for shawarma and souvenirs, we were willing to make one last stop at Hamat Teverya, a national park known for its hot springs (still in use by the spa across the street) and its synagogue featuring a brilliant mosaic floor. This mosaic is particularly interesting for its depiction of the zodiac, complete with what appears to be Helios, the Greek sun god, in the center. This has led to numerous speculative theories on what the Helios character really means in the context of this synagogue.

“This Enoch, whose flesh was turned to flame, his veins to fire, his eye-lashes to flashes of lightning, his eye-balls to flaming torches, and whom God placed on a throne next to the throne of glory, received after this heavenly transformation the name Metatron.” – Gershom G. Scholem

By this point, though we were enamored with the mosaic, we were ready to explore the modern city. Some students and I quickly headed for the nearest shawarma stand, and we were thrilled and overwhelmed to find three directly adjacent to one another, each proprietor holding up pieces of meat and falafel for us to sample. To be fair, we split ourselves in three equal groups and bought food from each enthusiastic vendor. Watching the cars drive by merely inches from my left shoulder, I ate my falafel in stunned silence.

At Paresky Snack Bar, I order my falafel with French fries. In Tiberias, my falafel comes with French fries inside.

Michelle, Queens College class of ’13, trying not to stare directly into oncoming traffic.

After this experience, I purchased a banana-date-pecan smoothie and walked down toward the water. What was far more interesting to me, however, were the rows upon rows of kitschy souvenir shops and stands on the walk down to the Sea of Galilee. I would be lying if I said souvenir stores and gift shops aren’t very important to me. As breathtaking as the national parks and archaeological sites were and will always be, my weekend was only fully complete after this indulgence.

I know of no other way to express my love for a place than with a tacky shot glass.

As we rode back to the kibbutz, I felt the warm satisfaction of having explored an entirely new place. That is what I’ll always remember.