ntro : New Programs, Facilities, and Research :

If the 1950s were a relatively quiet period for Williams and the sciences [and even the nation], the 1960s catalyzed a period of radical change for Williams, involving a great deal of debate and questioning of the College’s identity and mission. Fundamental changes changed the nature of the College. Major departures from past tradition reflected the turbulent atmosphere of the decade: the abolition of fraternities, the introduction of the Winter Study Program, and the approval of coeducation. Against that backdrop of institution-wide redefinition, broad change also occurred in the sciences, signaled by the establishment of new programs, the construction of a major, new, interdisciplinary research facility, the Bronfman Science Center, and the beginning of increased emphasis on research participation by science faculty.

1. A Redefinition of Biology

The biological sciences advanced rapidly during the 50s and 60s. Revolutionary discoveries, foremost among them the double helical structure of DNA in 1953, sped the development of molecular biology, and promoted a gradual restructuring of the biology curriculum.

By 1957-58, current research in Biology was covered by a course called “Evolution & Interrelationships of Organisms.” The course examined the concept of evolution and the evidence supporting it, an introduction to modern theories of the mechanism of speciation, and among other topics, the origin of life. No hint of the radical and novel burgeoning research in molecular genetics appeared in the course description. In 1959-60, “Principles of Genetics” examined topics such as genes, gene action, and genetic theories of evolution. Other new courses at this time, among them “Ecology”, “Vertebrate Embryology”, and “Cytology”, testified to growing diversity and variety in the department.

The topics of chromosomes and mutations at the chromosomal level first appeared in the Catalogue in the description of Biology 301, “Principles of Genetics,” in 1960-61, but may simply have referred to conventional genetic research originating in the 1910s with Thomas Morgan at Columbia.[1] The 1963-64 version of the course at last announced the arrival at Williams of the biological revolution. Now titled “Chromosomal Mechanisms,” it promised to cover “recombination and genetic fine structure analysis in micro-organisms; the molecular basis of heredity and mutagenesis; chemistry and replication of the nucleic acids.”[2] The course also studied the genetic code for protein synthesis, which had been deciphered only in 1961. That only two years separated research front results of the deepest significance and their undergraduate study reflected an increasingly professional and up-to-date faculty.

In 1969-70 “Quantitative Biology” used computer technology to study testable problems in Biology, and “Cytology” used newly acquired electron microscopes. The Department continued to diversify, offering coursework in Psychobiology, Ecology, Cellular Ultra-structure, Advanced Genetics, and Molecular Biology.

2. New Curricular Concentrations

For the non-biological sciences’ curriculum, the decade of the 60s was no less a time of bold experimentation, a period in which no fewer than four substantial curricular additions were created.

Astrophysics

In 1962-63 the college began to offer an Astrophysics major. New courses were offered: “The Solar System,” “Galactic Structure,” “Astrodynamics,” and “Stellar Structure.” “Astronomical Observation” was eliminated, but the Hopkins Observatory continued to be used. In 1971-72 the Astrophysics program was temporarily discontinued because of the sudden death of the college’s fourth astronomer, Professor Theodore Mehlin, who had been the only professor in the department. Eventually Prof. Mehlin’s successor, Professor Jay Pasachoff, succeeded in reviving and expanding the astrophysics program.

Psychology as a Natural Science

The Psychology department started offering natural science distribution credit for some of its courses in 1968. “Experimental and Quantitative Methods in Psychology,” “Animal Behavior” (listed also as a Biology course), and “Physiological Psychology” were all considered courses in science rather than social science. By 1971 Psychobiology was recognized as an area in which students might want to concentrate their studies. Interested students were advised to talk to a member of either the Biology or the Psychology departments in order to choose appropriate courses. By 1972 the Psychology department had added “Perception and Human Learning,” “Learning and Motivation,” and “Neuropsychology” to its selection of courses lying in the natural sciences. Given such a foundation, and the increasing importance of computer technology and artificial intelligence as a model for cognitive psychology, still later a Program in Neuroscience would emerge, involving close collaboration between members of the Biology and Psychology Departments.

Environmental Studies At Williams

Figure 29: Environmental Science on the Hoosic River

Along with civil rights and Vietnam, the turbulent 60s witnessed a great upsurge in environmentalism. Given the particular beauty of the Berkshire Mountains, it would have been virtually impossible for citizens of the Purple valley to ignore the national clamor for clean air and clean water. The newly confident and active environmental movement sparked the addition of several classes in the Biology and Geology Departments, and led to the creation of the Environmental Studies program in 1968.

The Biology Department had offered an Ecology course since the early sixties, and Geology followed with its first ecology courses in 1967: “Beach Processes and Ecology,” and “Paleoecology of Reefs.”

In 1968, these Ecology courses were expanded into a cross-disciplinary environmental studies program. Courses were offered by the Economics, Biology, Art, Chemistry, Political Science, and Geology departments. Williams prided itself “as the first Liberal Arts College to establish a special program and center in Environmental Studies.”[3]

History of Science and Non-majors Courses

Earlier efforts to create less apprentice-like approaches to the study of science were echoed during this time by the creation of several non-majors courses, and the reintroduction of courses in the History of Science.

In 1965 “Concepts in the Calculus,” an introduction to the ideas of the calculus, attempted to offer mathematics to non-mathematicians. “Elements of Modern Algebra” was also offered as a course for students who did not plan on continuing in mathematics. “Concepts in the Calculus” was discontinued the next year, but “Elements of Modern Algebra,” which became “Elements of Modern Finite Mathematics” survived for a few years longer.

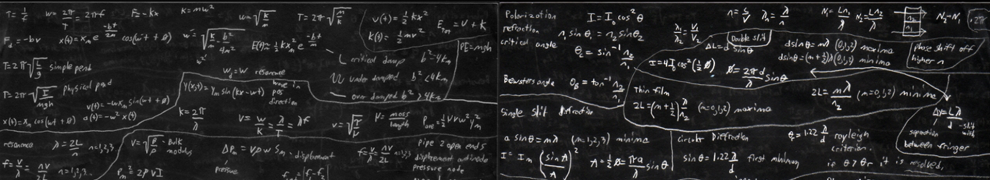

In 1966-67, the Physics department began offering courses for non-majors with little or no background in physics. “The Nature of Matter” was taught in non-technical language for humanities and social science students. In addition, two versions of an introduction to physics were offered, one with calculus for premedical students, and one with little mathematics, designed for those students with little background or experience in the sciences, but who needed to fulfill their distribution requirement. The Department usually offered one other course for non-scientists each year. Course content changed often, but titles included: “Natural Philosophies of Time,” “Introduction to Microphysics,” “The Historical Hydrogen Atom,” and “The Nature of Lasers and Light.”

In 1971-72, the College created two new departments, Sociology, and the History of Science. Courses in the history of science, which had been discontinued in 1954, were reintroduced in fall 1971 when Professor Donald deB. Beaver came to Williams. Professor Beaver offered courses in both the social sciences and the natural sciences. “Problems in the Recent History of Science” was designed for science majors only, so that there would be no difficulty in presuming advanced technical knowledge and ability. Other courses carried social science credit and were open to all. In 1972-73 Prof. Beaver and Mr. Lawrence Wright, Director of the Computer Center, team taught “Computers and Society,” involving computer science and social issues, a very early offering in that area. In 1985, Professor G. Lawrence Vankin of the Biology Department, a theoretical biologist with strong interest in the history and philosophy of biology, joined the History of Science Department, adding a valuable biological sciences component to its offerings, with courses such as “Evolution: the History of an Idea,” and “Theories of Human Evolution.”

3. New Facilities

The completion of the Bronfman Science Center in 1968 was the most significant physical change in science facilities at Williams during this period. Affecting every department, the Center redefined the study of science at Williams, and made for Williams a unique spot in small-school science departments across the nation.

Since the creation of Big Science during World War II there had been a very gradual, but continual loss of external funding for the sciences in small colleges and minor universities. More famous and more numerous professors at large institutions, with cadres of graduate student assistants, proved far more enticing to potential donors and investors, placing smaller schools at a severe disadvantage in the competition for support. President John Sawyer claimed that,

“…the surge of funds for scientific research and scientific education that has come in the last decade from government, foundations, and industry has by-passed the liberal arts colleges. It has flowed in massive amounts to larger research-centered institutes and universities, in rising amounts to rapidly growing state systems, and more recently even to secondary schools. But it has not nurtured the very important kinds of teaching and teachers and the serious scientific work that characterize the leading liberal arts colleges.[4]

The narrowing pipeline of support resulted in diminishing many science programs throughout the nation; smaller institutions which managed to maintain exceptional programs in the sciences often did so through more innovative use of their resources.

Figure 30: Addition to Thompson Physical Laboratory

Figure 31: Biology Laboratory 1964; Prof. William C. Grant right rear

In the early 60s Williams continued to rely heavily on its existing capital to insure the quality of its scientific facilities. For some time this method had proved effective. Both the Thompson Biology Laboratory and the Thompson Physics Laboratory had undergone massive reconstruction during 1950. At a combined cost of over $900,000 the building and architectural firm of Des Granges and Steffian had built additions to the original brick and steel structures.[5] The new laboratories and lab fixtures met the needs of the science departments. Physics and Biology, with 32 classrooms between them, could each accommodate over 400 students comfortably. With its 20 classrooms and basement laboratory, Thompson Chemistry Laboratory, after new plumbing and minor reconstruction, compared favorably with the best facilities of its size. Each department even had its own library which subscribed to a core of the most prestigious research journals in each of the respective subjects.

These renovations and additions were more than adequate to provide quality facilities well into the 1960s. Construction, renovation, and restoration costs for various science buildings between 1960 and 1964 totaled no more than $40,000. The only physical change of any note was the moving of Hopkins Observatory in 1961. In order to accommodate a new dormitory in the Berkshire Quadrangle, the trustees decided to have the 254 ton Hopkins Observatory moved 350 feet. It was the Observatory’s second move. In addition to the $15,000 cost to move the historic structure, the college also appropriated another $10,000 to refurbish the interior as an astronomy museum, and installed a $15,000 planetarium.[6]

Figure 32: New Chemistry Laboratory 1965

Figure 33: Professor Theodore Mehlin and new Planetarium

4. Bronfman Science Center

In 1962 a group of science faculty signaled a change in the College’s approach to its science departments. Increasing migration of grants and talent to large universities and institutes required new measures be taken to restore the science departments to the forefront of educational scientific facilities. In 1962 Professors Fielding Brown and David A. Park of physics, William C. Grant, Jr. of biology, and J. Hodge Markgraf of chemistry instigated and engineered a formal proposal to construct a single new science center which would house all of the science labs. The cross-fertilization of ideas which was the objective of the new center was regarded as a highly innovative concept, and plans for its construction were approved.

Figure 34: Bronfman Science Center under Construction

Figure 35: Bronfman Science Center, 1967

Over the course of the next four years, contributions and grants were vigorously solicited. The Bronfman family, headed by Charles R. Bronfman, began the funding with a contribution of $1.25 million dollars. In 1964, construction of the new $3.9 million dollar science building, the Bronfman Science Center, began. By 1968, Williams had one of the most sophisticated and innovative scientific facilities of any college.

The basic concept behind the building’s multi-departmental nature was a belief that:

“advanced research by both students and faculty is vital in modern science education, and that the interdisciplinary exchange among students and teachers in the different branches of science can create a stimulating intellectual environment[7].

The building was designed to address this beneficial exchange of information in two ways. First, the research wing of the facility was designed to place faculty members and students from different scientific disciplines in close proximity to each other. Each of the laboratories of the individual faculty members was placed adjacent to that of another professor from a different department. Student labs were also grouped together, with the aim of diversifying discussion and ideas. Second, the Center was designed with a central core of scientific instruments available to every department. Original equipment in this section included the college’s first computer, an IBM 1130 digital computer, spectrophotometers, and facilities for constructing simple lab devices and equipment. In addition, space was provided for electron microscopes and x-ray equipment, which were finally obtained in 1969.

Figure 36: IBM 1130, Bronfman Science Center

Figure 37: Professor G. Lawrence Vankin, students, and new electron microscope

Figure 38: Physics experiment 1968

The science center was filled with innovative design concepts which aided in research, as well as the operation of the building itself. Drainage ran through pipes made of pyrex glass, both more resistant to corrosive materials than conventional metal drains and more easily unclogged. One Geology lab was built with a stone pier that touched no part of the building and was anchored in bedrock. Consequently, geologists could conduct sensitive seismological experiments without fear of contamination by vibrations originating inside or outside the building. The Center even maintained a department for care of the experimental animals essential to many of the biology and psychology experiments.

The highly sophisticated Bronfman Science Center not only helped to lure undergraduates to Williams, but it also served to lure many professors. According to Samuel Matthews, Samuel Fessenden Clarke Professor of Biology,

“…several of the scientists we presently have here came largely because the Bronfman Science Center was being programmed. And in recruiting this year I know what a pull the Center has had in encouraging people that we want to come to Williams.”[8]

There can be no doubt that the college’s newer, more aggressive and innovative approach to integrating the sciences through Bronfman was a success. The sciences, with psychology, created a new administrative committee reflecting that integration, the Science Executive Committee (SEC), composed of a representative from each department (usually the Chair), two untenured professors, and the Coordinator of the Bronfman Science Center.

As a general supervisory committee, the SEC concerns itself with affairs of common, extra-departmental interest. Provost and Professor of Psychology George Goethals suggests that the sciences benefit somewhat from their possession of a centralized representative body.[9] The SEC, as a governing body for the sciences and psychology (DIII & P), makes divisional policy and responds to the decisions of the administration. Normally the Chair of the SEC acts as liaison between the sciences and the Administration. The SEC resolves questions of space utilization, plans funding initiatives, and makes recommendations for new construction.[10] The SEC does not take a role in tenure decisions, which are left to the individual departments and the Committee on Appointments and Promotions.[11]

Less heterogeneous than the humanities and social sciences, the natural sciences coordinate and plan unified requests for funds and other support from the Administration. As a result they are marginally more successful, because they do not undermine each other in the way that the other two divisions are apt to. The Administration benefits as well, because it has fewer factions to deal with every time operating budget or capital issues come up.

The integration brought about by the Bronfman, however, did not lead to abandonment of the departmental system, or the older lab buildings. When finished, the new building had only eight real classrooms and one 285 seat lecture hall. The older buildings in the science quadrangle remained essential to the science program for both classrooms and faculty offices. Indeed, the same year that construction began on Bronfman the college spent $85,000 on restorations to the Thompson Chemistry Laboratory building. In 1970, Clark hall also underwent further restoration, at a cost of nearly $310,000.

5. Williams Enters The Computer Age

In 1967, acquisition of an IBM 1130 computer, a general purpose scientific electronic digital computer, had widespread curricular influence in the natural and social sciences. Departments including Chemistry, Biology, Economics, Geology, Mathematics, Political Science, and Psychology offered at least one course that used the computer. The College offered short, non credit lecture series to teach students how to program in FORTRAN. Once students had taken one of these courses they could have access to the 1130. One reason that course use of the computer remained relatively limited was that input required batch lots of keypunched cards, and turnaround and error correction time were enormous in comparison with later standards. Several weeks before the end of each semester, the Bronfman corridors leading to the computer’s job drop off and output pick up would be littered day and night with students trying to get their programs to produce intelligible results.

The Mathematics department, however, took particular advantage of the new computer, offering special courses in Computer Science, and other mathematics courses in which the computer could be used to demonstrate ideas and solve problems. “Numerical Analysis,” a course on methods of handling large scale computations using computers, was the first formally to mention computers in the curriculum.

6. The Growth of Research

Before 1960, faculty members in the sciences did virtually no research. Physics professor Fielding Brown, who came to Williams in 1959, has said that there was no research done in the physics department before the early 1960s. Professor Brown was one of the first to receive a nationally funded grant for his research.

Geology Professor William Fox recalls a discussion at the faculty club in the first semester he was here with Professor Allyn Waterman of the Biology department. Waterman, one of only a handful of Williams scientists to have a research grant, asked Fox about his research and how soon he would be applying for a grant of his own. Encouraged by Waterman’s enthusiasm, Fox wrote the proposal over Christmas break 1961, and sent it in. In April 1962 he received $32,000 from NSF, and was at work in the field that summer.

Research was gradually to become an important part of professors’ lives at Williams, as demonstrated by publication of the first Report of Science at Williams, for 1963-64.[12] If relative lack of substantial research activity had been one reason why such a publication had not appeared before, increasing numbers of research investigations together with a new feeling of common identity amongst science faculty across departments helped bring the volume into being. By far the largest section of the Report was devoted to research publications, including senior honors theses and papers published by faculty. Professors who listed at least one abstract in the Report usually listed two or three, frequently written in conjunction with a student. The Report also contained news about student majors’ post-graduation plans, lectures and colloquia, and trips taken by professors and students. That the Report was published at all indicated the beginnings of a significant transformation in the professional identity and nature of the science faculty.

The Report also records that funds for research had begun flowing into Williams in the early sixties. Biology professors Grant, Whitehead, and Waterman brought in over $80,000 in 1963-64. On completion of the Bronfman Science Center in 1968, professors began working to consolidate and share expensive equipment, thereby making more efficient the use of grant money.

The physical and academic research changes in the working environment of Williams began to affect faculty appointments in the mid sixties. Before Bronfman, professors had not been expected to perform research; those who did publish mostly wrote textbooks reflecting the deep, almost exclusive, commitment of the College and its faculty to teaching. In the post-Bronfman era this was not the case. Geology Professor Reinhard Wobus recalled that someone who did not perform research could no longer be considered for tenure track placement. Chemistry Professor Hodge Markgraf stated that research became a requirement to show that one had an active, curious, and dynamic mind. What was sought after in those early transitional years was evidence of “sustained curiosity,” and the asking of a high “quality of questions.” Markgraf pointed out that successful research alone is not and was not a guarantee of receiving tenure at Williams. Professor Brown noted that what was required was to “show signs of life,” and to be flexible and up-to-date, especially with regard to courses taught. Thus, in the sixties, research came increasingly to be emphasized, expected, and desireable, at first primarily for its beneficial effects on the teaching ability of the professor and the learning process of the student. By the seventies, faculty in the sciences were publishing on average one research paper per year per faculty member.[13]

Parallel to the growing faculty emphasis on research was student participation in research as part of the honors program. In 1953, 49 students were awarded a degree with honors; 14 of them were science majors. In 1957, the numbers had grown to 19 science majors of a total of 60 honors students. After Bronfman, student research reached and maintained new prominence, as demonstrated by the annual volumes of the Report . Nearly one-sixth of the research publications originating at Williams are co-authored by students.[14]

Not since the 1960s has science at Williams undergone such enormous, significant, and rapid change. The Bronfman Era was a crucial time of redefinition, a modernization which clearly set science education and research at Williams on a new course.

[1] The Williams College Catalogue, 1961-62, (April 1961), p. 70. | Back |

[2] The Williams College Catalogue, 1963-64, (April 1963), p. 73. | Back |

[3] The Williams College Catalogue, 1970-71, (April 1970) In February 1993, the Center for Environmental Studies celebrated its 25th anniversary, as one of the pioneering Environmental Studies Programs in the United States. | Back |

[4] John Sawyer, quoted in “Sloan Foundation Gives $500,000 to Williams For Science Program,” Williams Alumni Review, vol. 59, No. 2 (Feb. 1967), p. 10. | Back |

[5] Williams College Building and Grounds, The Williams College Value Book, Williams College 1985. Except where otherwise noted all statistics and figures for this section should be credited to this source. | Back |

[6] Theodore G. Mehlin, “Williams College Renovates Hopkins Observatory,” Sky and Telescope, Vol. 23, No. 2 (February 1962), Reprint, p. 1. | Back |

[7] “Bronfman Family is Honored at Science Center Dedication,” Williams Alumni Review, Vol. 60, No. 3 (May 1968), p. 7. | Back |

[8] Ibid., p. 5. | Back |

[9] Interview with Professor George Goethals, 28 April 1992. | Back |

[10] Ibid. | Back |

[11] Ibid. | Back |

[12] Report of Science at Williams, 1963-64, (Williamstown, Mass., Williams College, 1964). Hereafter, simply Report, 19xx-xx+1. | Back |

[13] Donald deB. Beaver, unpublished count of research productivity of Williams science faculty, taken from Report, vols. 1970-71 through 1986-87. | Back |

[14] Ibid. | Back |