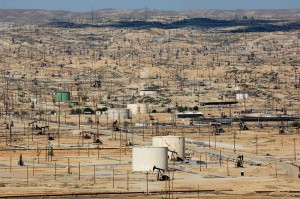

Photo of an oil field in McKittrick, Kern County, entitled ‘What hell must look like[1] Source: Ben Klocek (CC by 2.0)

Rosario Garcia, a resident of the city of Shafter, Kern County, has had great trouble breathing for the last few years.[2] He contracted Valley Fever, a disease triggered by fungi in the soil that get stirred into the air by activities that disrupt the soil, like farming, construction, and oil extraction. Garcia adds that two of his close friends died from Valley Fever. He attributes the prevalence of the disease within his community to the impacts of an unconventional oil and gas extraction method known as hydraulic fracturing (fracking)[3], which industries practice throughout Kern County.

Garcia’s son Miguel, 9 years old, contracted asthma. Miguel says, “When I have asthma, my chest hurts, I have headaches. It feels like if my heart was hurting but it’s actually my chest, and then I feel like if I was going to die. I have to not play around with dirt, not be outside, and stay housy. I get mad because I can’t play outside with my friends.”[4] The pattern is clear to residents; a lot of people are getting sick.

Juan Flores of the Center for Race, Poverty and the Environment illustrates this community’s first experiences with the health impacts of fracking: “Last year, when we had the grand opening of the [community] garden, we noticed they were putting those pumps up, that there was some drilling was going on. The smells could be so bad that it could actually hurt you. You could get headaches, be dizzy, get nauseous. So that’s when we got all into getting to know more about fracking, and getting community members educated.”[5]

In 2014, Rodrigo Romo and Anabel Marquez, community activists from Shafter, addressed a letter to Governor Jerry Brown of California, writing, “We are the ones living with fracking every day…We can see wells surrounding our elementary schools, our churches, our farms and our homes…Those we care about are beginning to suffer from headaches, nosebleeds, rare cancers and respiratory diseases associated with oil drilling and extraction.”[6] They invited Governor Brown to visit Shafter, so he might come to understand their suffering and put a stop to fracking. Governor Brown ignored the request.

The gas flare in an oil field just north of Shafter, Kern County[7] Source: Michael Fagans/The Californian

On top of contaminating the air and water, fracking wells torment nearby residents psychologically. When Vintage Petroleum began extracting oil across the street from the home of Shafter residents Walt and Marilee Desatoff, conditions became unlivable. Walt cited the jet-engine roar and bright blaze generated during weeks of nonstop flaring (burning off of waste gases) as the most bothersome. He explained, “The first few hours it’s not so bad. But after a day, it starts really getting on your psyche and your sense of sanity.”[8] Marilee adds, “We could not have family over anymore. We could not sleep at night because we would hear this noise and that became a stressful situation for us.”[9] When Vintage offered to buy the couple’s property, the Desatoffs surrendered. Marilee felt heartbroken about leaving the home that once belonged to her grandparents, but she “couldn’t deal with the pain anymore.”[10]

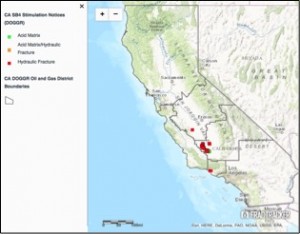

In a complaint filed against Governor Brown and the Division of Oil, Gas & Geothermal Resources, Rodrigo Romo alleged that his two daughters suffer from psychological distress and fear for their health because stimulated hydraulic fracturing wells operate in close proximity to their public schools in Kern County.[11] Juan Flores reported from his hometown of Delano, CA that residents fear the fracking industry’s practice of injecting wastewater into unlined pits is contaminating their sources of drinking water: “No one from this community will drink from the water from out of their well. The people are worried. They’re scared.”[12]

A University of Pittsburgh public health study provides evidence that stress is common around fracking operations. Researchers documented the self-reported health concerns of Pennsylvania residents living near fracked wells.[13] While participants cited a range of impacts, including rashes, sore throats, shortness of breath, nausea, and headaches, the most commonly reported impact was psychological stress; seventy-six percent of participants reported experiences of stress from living near drilling activity. Whether or not the physical conditions were due to direct exposure to chemical pollutants, stress itself can cause serious, physical health complications.[14]

Dismissing the claims of fenceline communities

Industry advocates such as the Western States Petroleum Association (WSPA) frequently dismiss the claims of community members and activists regarding the danger of fracking, asserting that oil and gas operators have employed unconventional extraction methods for more than 60 years. [15] Their reasoning implies that because fracking has not caused any major disasters over those decades, current concern is unwarranted or even irrational.

The WSPA also respond to Kern County residents’ claims of environmental harm through denial of impacts. Representatives of the oil industry often site a report by the California Council on Science and Technology (CCST) for vindication. The California Natural Resources Agency commissioned CCST to conduct an independent assessment of existing scientific information on hydraulic fracturing.[16] Researchers reported: “Direct impacts of hydraulic fracturing appear small but have not been investigated. Significant gaps and inconsistencies exist in available voluntary and mandatory data sources,” which “limit assessment of the impacts of hydraulic fracturing.”[17]

The WSPA selects pieces of the CCST conclusion to repeat while omitting others, stating “During the decades it has been used, hydraulic fracturing has never been shown to adversely impact the state’s environment, drinking water supply or pose any risk to nearby residents. In fact, to date there has not been a documented case of fluids used in fracturing operations entering a drinking water aquifer.”[18] The WSPA does not mention that fracking in California maintains its supposedly clean track record in the context of weak or nonexistent monitoring. Bill Allayaud of the Environmental Working group explains that before reporting began on FracFocus.org in 2011, fracking operated “…for five decades with basically no oversight. People could have pollution in their groundwater and we would have no idea.”[19] The WSPA’s claims of innocence also indicate that in its eyes, residents’ lived experiences do not constitute ‘documented cases’ of adverse impacts.

The rhetoric of Governor Jerry Brown and his administration at times sounds shockingly similar to that of the oil and gas industry. Activist Brenna Norton reported that after telling Governor Brown that she works with people who have become sick from fracking operations in Los Angeles, Brown countered, “That’s not true. Fracking can be done safely and has been happening [in California] for 60 years.”[20] The chief deputy director of the California Department of Conservation wrote, “We have no direct evidence that any harm has been caused by the practice in California. We believe the regulations we’ve created, atop existing well construction standards, will protect the environment.”[21] It seems the administration’s definition of what constitutes ‘direct evidence’ excludes the experiences of the community members most affected by fracking.

Activists express opposition to fracking while Governor Brown delivers a speech in 2014 Source: Jae C. Hong[22]

After audience members shouted “Ban fracking!” during Governor Brown’s speech at the California Democratic Party’s convention in 2014, Brown countered that California is leading the way on addressing climate change, and stressed that the solution rests not with changing “one thing” (fracking), but “a whole series of things.”[23] By considering only the global impacts of fracking, such a response discounts the bodily and environmental harms that oil and gas extraction inflicts on fenceline communities.

The confusion of cumulative impacts

Fracking continues to operate under weak state and federal regulations. How do government officials ignore community members’ accounts of suffering, palpable evidence of personal harm? For one, these communities bear the weight of multiple layers of environmental harm, making it difficult for residents to tease out the impacts of new fracking wells alone. The air quality in Kern County ranks amongst the worst in the United States. Kern is number five in a list of the most ozone-polluted US counties, number two in a list of US counties most at risk of short-term particle pollution, and number two for year-round particle pollution.[24] Asthma rates in the southern tip of the San Joaquin Valley are triple the national average, and chronic pulmonary disease, cancer, and Parkinson’s disease is overrepresented in the population.[25]

Rock Zierman, CEO of the California Independent Petroleum (CIPA) took advantage of the presence of multiple pollutants when he described Kern County as, “…a nonattainment area, not just because of oil and gas but because of automobiles and all kinds of other industries. There’s no way to know whether we are the source of whatever they found, if they found anything.”[26] One might hope that the presence of multiple sources of environmental harm would not excuse inaction on the part of the government and industry, but rather motivate stricter fracking regulations to protect an already overburdened community.

Documenting pollution

Despite the challenge of cumulative impacts, residents in Kern County document fracking-generated pollution, in order to support claims that fracking is indeed damaging their mental and physical health, their soil, their water, their air. One afternoon in 2013, community activist Tom Frantz videotaped an oily, brown mixture followed by a sudsy-looking liquid flowing into an open, unlined Vintage Petroleum pit in Shafter. [27]

Frantz’s actions yielded results. In response to his video, the Central Valley Regional Water Quality Control Board launched an investigation into the company’s waste pits.[28] Vintage only had permission to discharge drilling muds and boring wastes into the pit, yet the Board found that operators illegally dumped 126-168 gallons of fracking fluids, containing a stew of chemicals such as benzene (a carcinogen), boron, salts, and a stew of other chemicals.[29] Vintage agreed to pay a maximum fine of $60,000 for their water quality violations, marking the first time California fined a company for an action in the process of fracking.[30]

Residents in Shafter are concerned about constant flaring at a fracking site immediately upwind of a school and community garden. In December of 2014, they collected an air sample from the site using the Bucket, a piece of monitoring equipment courtesy of the Global Community Monitor organization.[31] The Bucket uses a pump system to gather a few liters of air into a lined bag. The sample is then sent to a certified laboratory, where it is tested for over 70 Volatile Organic Compounds and 20 sulfur-containing compounds.[32]

An analysis of the Shafter sample detected the presence of several toxic chemicals, including toluene.[33] A study launched by the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce reported toluene as present in 29 hydraulic fracturing products used by oil and gas service companies between 2005 and 2009.[34] Chronic exposure to toluene, both regulated under the Safe Drinking Water Act for its risk to human health and included as a hazardous air pollutants under the Clean Air Act, can damage the nervous system, liver, and kidneys.[35] The sample also contained methane at 2.7 ppm, a concentration higher than normal background levels. Elevated methane levels occur frequently near fracking wells.[36] It seems that this instance of community science has fallen on deaf ears; no online news sources, government reports, or industry communications mention the air sample’s toxic contents.

Kern County resident and Clean Water Action community organizer Rosanna Esparza collected health surveys of residents and their children in the town Lost Hills.[37] In the Lost Hills Oilfield, adjacent to the town, at least 244 wells have been fracked. A January 2015 joint report from the Clean Water Fund and Earthworks included her findings.[38] In Lost Hills, 92.3 percent of residents surveyed reported smelling odors in their homes and community, which some described as petroleum, burning oil, or rotten eggs. Symptoms experienced while the odors were present included headaches, nausea, dizziness, burning or watery eyes, and throat and nose irritation.[39] While this report received attention in news sources like The Bakersfield Californian, Rock Zierman of CIPA was quick to dismiss its findings, pointing to environmental impact reports from other areas that came to different conclusions, “based on real science.”[40]

Intended audiences have treated the community’s work with disrespect. Nonetheless, these examples of dedicated citizen science demonstrate that Kern County residents will not accept a position as passive victims of environmental injustice.

Community organizer Rosanna Esparza with a Lost Hill Health Survey participant Source: Sarah Craig/Faces of Fracking[41]

References:

[1] Ben Klocek, “What hell must look like,” Flickr, Feb. 10, 2008, https://www.flickr.com/photos/benklocek/2331865111/in/album-72157604116382511/.

[2] Mark Hertsgaard, “If Jerry Brown is So Green, Why Is He Allowing Fracking in California?” The Nation, June 18, 2014, http://www.thenation.com/article/if-jerry-brown-so-green-why-he-allowing-fracking-california/.

[3] Lisa Morehouse, “Fracking California: The view from Kern County,” KALW Local Public Radio, June 16, 2014, http://kalw.org/post/fracking-california-view-kern-county#stream/0.

[4] Ibid [3].

[5] Ibid [3].

[6] Rodrigo Romo and Anabel Marquez, “Letter to Governor Jerry Brown,” Center on Race, Poverty, & the Environment, 2014, http://www.crpe-ej.org/crpe/images/stories/campaigns_climate/Community_Letter_Gov_Kern.pdf.

[7] Michael Fagans, “A gas flare towers over a two-sided fence at an oil field north of Shafter on Merced Avenue on Tuesday night,” The Bakersfield Californian, Sep. 1, 2023, http://www.bakersfield.com/news/2012/09/02/the-sound-and-the-fury-gas-flare-wears-on-shafter-area-residents.html.

[8] Knudson, Tom, “Fracking near Shafter raises questions about drilling practices,” Merced Sun Star, June 30, 2013, http://www.mercedsunstar.com/news/state/article3278073.html.

[9] NRDCflix, A Home Surrendered (NRDC), YouTube video, 4:28, September 9, 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1P1yQGhA5No.

[10] Ibid [8].

[11] Rodrigo Romo v. Edmund G. Brown, Division of Oil Gas & Geothermal Resources, Steven Bohlen: Complaint for Injunctive and Declaratory Relief, 1 (S.C. CA 2015). http://www.crpe-ej.org/crpe/images/stories/press_releases/SignedComplaintSmaller.pdf.

[12] Stephen Stock, Liza Meak, Mark Villarreal, and Scott Pham, “Waste Water from Oil Fracking Injected into Clean Aquifers,” NBC Bay Area, November 14, 2014, http://www.nbcbayarea.com/investigations/Waste-Water-from-Oil-Fracking-Injected-into-Clean-Aquifers-282733051.html.

[13] Kyle J. Ferrar, Jill Kriesky, Charles L. Christen, Lynne P. Marshall, Samantha L. Malone, Ravi K. Sharma, Drew R. Michanowicz, and Bernard D. Goldstein. “Assessment and longitudinal analysis of health impacts and stressors perceived to result from unconventional shale gas development in the Marcellus Shale region.” International journal of occupational and environmental health 19, no. 2 (2013): 104-112.

[14] University of Pittsburgh Schools of the Health Sciences, “Many stressors associated with fracking due to perceived lack of trust,” ScienceDaily, April 29, 2013, <www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2013/04/130429130550.htm>.

[15] WSPA, “Hydraulic Fracturing,” WSPA, 2013, https://www.wspa.org/issues/hydraulic-fracturing.

[16] CCST, “Well Stimulation in California,” CCST, October 15, 2015, http://ccst.us/projects/hydraulic_fracturing_public/SB4.php.

[17] Jane C.S. Long, Jens T. Birkholzer, Laura C. Feinstein, “An Independent Scientific Assessment of Well Stimulation in California: Summary Report,” CCST, July, 2015, http://ccst.us/publications/2015/2015SB4summary.pdf.

[18] Ibid [15].

[19] Ibid [8].

[20] Brenna Norton, “Dear Governor Brown: On Fracking, It’s Time to Get Your Head Out of the Clouds,” IndyBay.org, January 15, 2014, https://www.indybay.org/newsitems/2014/01/15/18749267.php

[21] Juliet Williams, “Gov. Jerry Brown Clashes With Environmentalists: No Evidence Fracking Has Harmed California,” TPM News, February 6, 2015, http://talkingpointsmemo.com/news/california-fracking-governor-jerry-brown.

[22] Juliet Williams, “Fracking puts California governor, environmentalists at odds,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, February 6, 2015, www.post-gazette.com/frontpage/2015/02/06/Fracking-puts-California-governor-environmentalists-at-odds-1/stories/201502060188.

[23] CADEM.org, Gov. Jerry Brown 2014 CADEM Convention (CADEM), YouTube video, 12:43, March 8, 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VfmvfIFBgAk.

[24] American Lung Association, “State of the Air 2015,” American Lung Association National Headquarters, Chicago, IL, 2015, http://www. stateoftheair. org/2009/states/wisconsin.

[25] Rosanna Esparza, “Wearing a respirator in Bakersfield—where the town motto is “life as it should be,” Clean Water Action, February 23, 2016, http://www.cleanwateraction.org/2016/02/23/wearing-respirator-bakersfield%E2%80%94where-town-motto-life-it-should-be.

[26] Courtenay Edelhart, “Environmental group says oil and gas industry hurts air quality,” The Bakersfield Californian, January 22, 2015, http://www.bakersfield.com/news/2015/01/22/environmental-group-says-oil-and-gas-industry-hurts-air-quality.html.

[27] Ibid [8].

[28] Ibid [8].

[29] Mark Grossi, “Fracking probe expands in Central Valley,” The Fresno Bee, Nov. 2, 2013, http://www.biologicaldiversity.org/news/media-archive/a2013/Fracking_FresnoBee_11-2-13.pdf.

[30] Allen Martin, “Oil Company Caught Illegally Dumping Fracking Discharge In Central Valley,” CBS SF Bay Area, Nov. 26, 2013, http://sanfrancisco.cbslocal.com/2013/11/26/oil-company-caught-illegally-dumping-fracking-discharge-in-central-valley/.

[31] Global Community Monitor, “Fracking without Adequate Regulation even in Environmentally Friendly California”, Air Hugger, Jan. 15, 2014, https://airhugger.wordpress.com/2014/01/15/fracking-without-adequate-regulation-even-in-environmentally-friendly-california/.

[32] Global Community Monitor, “Community Monitoring Tool Kit,” GCMonitor.org, http://www.gcmonitor.org/communities/start-a-bucket-brigade/community-monitoring-tool-kit/.

[33] Ibid [31].

[34] United States House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce, “Chemicals Used in Hydraulic Fracturing,” Coservation.ca.gov, April, 2011. http://www.conservation.ca.gov/dog/general_information/Documents/Hydraulic%20Fracturing%20Report%204%2018%2011.pdf.

[35] Ibid [34].

[36] Ibid [31].

[37] Tara Lohan, “Rosanna Esparza,” Faces of Fracking, 2014, http://www.facesoffracking.org/story/rosanna-esparza/.

[38] Jhon Arbelaez and Bruce Baizel, CALIFORNIANS AT RISK: An Analysis of Health Threats from Oil and Gas Pollution in Two Communities,” Earthworksaction.org, January, 2015, https://www.earthworksaction.org/files/publications/CaliforniansAtRiskFINAL.pdf.

[39] Ibid [38].

[40] Ibid [26].

[41] Ibid [37].