In the Vol. 1 Issue 11 of Everywoman published in 1970, the short dramatic sketch titled “Conference in Black” by Black author Caroline Laud dives into the differences in perception between white feminists and feminists of color.

Women of color were disproportionately victimized by a lack of reproductive rights. In New York, around 80 percent of the deaths caused by illegal abortions were Black or Puerto Rican women (Davis 117). The negative conditions were furthered by the general lack of accessibility women of color had to these health procedures. Published in 1970, Vol. 1 Issue 11 of Everywoman dives into the differences in perception between white feminists and feminists of color. The simple, black and white, news and current affairs magazine aimed for an audience of “real women” including women of every race, feminists and non-feminists alike. The issue contains an article about a conference with two contrasting views about the same conference, one written by the Black author Caroline Laud and the other by a white, anonymous author. Laud chose to write her section in the form of a short dramatic sketch called “Conference in Black.” The piece is formatted as a call and response between white, “Liberal Women” and Black Women (Laud 5). In the sketch, the liberal women state, “tummy too round” and the Black women reply “Goddamn baby inside…/ Can’t afford to keep it… Can’t afford to get an abortion” (Laud 5). In the performance of the sketch, those playing the liberal women hold mirrors to their faces connoting vanity. The line “tummy too round” makes the white women seem absorbed only with their looks. They are worried about becoming too fat while Black women struggle with an unplanned pregnancy that they “can’t afford.” Laud claims that women of color have even less agency over their reproductive health than their vain, white counterparts.

The contrasting side to the Everywoman article “Conference in Black,” titled “and White,” was written by an anonymous white author.

Considering that the issue of reproductive rights especially impacted women of color, one would expect that women of all identities would unite under the cause. But in actuality, the issue was extremely divisive. Most of the women who supported abortion rights were white, middle-class, liberal woman. On the other hand, as Angela Davis observes in the chapter “Racism, Birth Control, and Reproductive Rights” of the book Woman Race Class published in 1981, the “ranks of the abortion rights campaign did not include substantial numbers of women of color” (Davis117). Furthermore, white women did not seem to understand or acknowledge this divide. The contrasting sides to the Everywoman article “Conference in Black / and White” highlights this discrepancy. Where Laud chooses to write about the inequity within the movement, the anonymous white author frames the conference with a much more positive tone (Conference 5). She reflects that at the conference, “we shared our thoughts, our feelings, our conflicts, our love. Sisters who had never met felt a sense of community with each other.” The stark contrast between these two works reflects the obliviousness of many white liberal feminists to the struggles of women of color.

Many women of color did not support the abortion rights campaign because white liberal feminists failed to understand the significance of including sterilizations within the policies. Within the U.S. history of birth control lies a history of eugenics. In 1905 President Theodore Roosevelt proclaimed that “race purity must be maintained” and the falling rates of white births were “race suicide” (Davis 121). Later the Eugenics Society was formed and soon after claimed: “twenty-six states had passed compulsory sterilization laws [and] thousands of ‘unfit’ persons had already been surgically prevented from reproducing” (Davis 121). The American Birth Control League also formed and supported birth control specifically among Black people. Its successor, the Birth Control Federation of America, planned a “Negro Project” in 1939. The project claimed that the black population in the South “breed carelessly and disastrously, with the result that the increase among Negroes, even more than among whites, is from that portion of the population least fit, and least able to rear children properly” (Davis 123). Furthermore, so-called “population control” was also deeply rooted in the very beginning of the birth control movement. Margaret Sanger, a champion of birth control, advocated for its usage to reduce births by women of color. Sanger wrote in a letter to a colleague, “We do not want word to get out that we want to exterminate the Negro population” (Davis 125).

These practices continued into the 1970s. At the beginning of the abortion movement, many assumed that population control through abortions and permanent contraceptives such as sterilization would be the solution to poverty. Reduced family sizes would mean fewer people to support and feed. The U.S. government supported such population control efforts, creating sterilization projects within the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. According to the news section of Vol. 5, Issue 6 of Women’s Press, in the eight years before the issue was published in 1975, “the U.S. government has increased its population control budget by 6,000%” (Houghma 4). These projects often targeted women of color and had a much larger impact than was advertised at the time. In 1972 the department claimed that around 16,000 women and 8,000 men had been sterilized (Davis 120). But today, Carl Shultz, director of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare’s Population Affairs Office, estimates that between 100,000 and 200,000 sterilizations had actually been funded that year by the federal government.

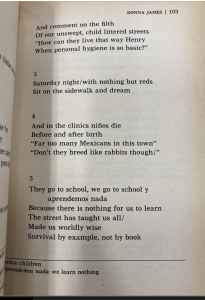

The poem “Creciendo en el barrio,” by Chicana poet Donna James, explores how the horrors of sterilization impact the speaker’s community. The poem is found in the anthology From the belly of the shark.

In response, people of color began to write about the horrors of the government’s push for “population control.” Chicana/o poets in particular explored the terrible effects of mass sterilizations on their communities. For instance, the anthology From the belly of the shark contains several poems by Chicana/o poets which express individual experiences with the issue. Published in 1970, the anthology includes works by Chicanos, Inuits, Hawaiians, Indians, and Puerto Ricans in the United States. In particular, the poem “Creciendo en el barrio” by Chicana poet Donna James, explores how the horrors of this practice impacts the entire community through its children (James 104). “Creciendo en el barrio” translates to growing up in the barrio, a lower-income Spanish-speaking area of a town or city. In the fourth stanza, James exposes the reality of the so-called “population control” initiatives in these communities.

And in the clinics ninos die

Before and after birth

“Far too many Mexicans in this town”

“Don’t they breed like rabbits though”

The children are dying in the clinics “before and after birth.” In the hospitals, women are forced to get sterilizations and, if they do have a child, the community is so harmful that some children do not survive. James demonstrates that neither their nation’s government nor their hospitals value the lives of those within the barrio. Through the use of quotations, James attempts to capture the rationale of these institutions. To outsiders, the people in the barrio are considered “Mexicans” even though they reside in America. By not referring to these people as “Mexican-American,” they are categorized as other. The visitors continue to state, “don’t they breed like rabbits though,” reducing the people of the community to rabbits, an animal considered small prey that reproduces extremely rapidly. The government systems are taking advantage of this community through a mindset of dehumanization.

Thus, as Davis claims in the book Woman Race Class, although many of these women were “in favor of abortion rights [it] did not mean they were proponents of abortion” (Davis 118). Women of color understood the horrors that accompanied a lack of reproductive rights, yet they also had experienced the permanent, non-consensual effects of mass sterilizations. Morally, many could not support the abortion movement if they were not guaranteed protection.

Works Cited:

“Conference in Black and White.” pp. 4. Everywoman, vol. 1, no. 11. Dec. 1970, pp. 5

Davis, Angela. “Racism, Birth Control, and Reproductive Rights.” Woman Race Class, Vintage E-Books, 1981, pp. 117-127

Houghma, Ishi. “News.” Women’s Press 5, no. 6 September 1, 1975 pp.4

James, Donna. “Creciendo en el barrio.” From the Belly of the Shark : A New Anthology of Native Americans : Poems by Chicanos, Eskimos, Hawaiians, Indians, Puerto Ricans inthe U.S.A., with Related Poems by Others. 1st Vintage Books ed. New York. 1973.pp. 102-104

Laud, Caroline. “Conference in Black and White.” pp. 4. Everywoman, vol. 1, no. 11. Dec. 1970, pp. 4