The front page article of Triple Jeopardy / Racism Imperialism Sexism Vol. 3 Issue 3, “Sterilization: La Operacion/ The doctor may need it more than you!” by Gloria Rivera exposes the medical practices surrounding sterilization at the time. Published in 1974, Triple Jeopardy / Racism Imperialism Sexism was produced by the Third World Women’s Alliance.

The belief that population control could combat poverty was not only held by policymakers in the U.S. government. On a smaller scale, hospitals and individual doctors supported the movement as well. In the front page article of Triple Jeopardy / Racism Imperialism Sexism Vol. 3 Issue 3, “Sterilization: La Operacion/ The doctor may need it more than you!,” the author Gloria Rivera exposes the medical practice surrounding sterilization at the time(Rivera 1). Published in 1974, Triple Jeopardy / Racism Imperialism Sexism was produced by the Third World Women’s Alliance. Racism is listed as the first of the three issues that make up the “Triple” of the title, indicating that the periodical was written primarily for an audience of women of color. This article was also written in Spanish, increasing accessibility to Latin American women whose primary language is not English. It includes a combination of both jarring second-hand quotes from medical professionals at the time and advice for women of color to avoid unwanted sterilization procedures. The article begins by exposing the “for the greater good” mentality which medical professionals used to rationalize their actions. A Gynecologist named Dr. Wood is quoted claiming that, “People pollute, and too many people crowded too close together cause many of our social and economic problems… As physicians we have obligations to our individual patients, but we also have obligations to the society of which we are a part” (Rivera 1).

In addition to “population control,” there were monetary incentives to perform sterilizations. The more procedures a hospital performed, the more government funds it received. In the article “Sterilization: La Operacion/ The doctor may need it more than you!,” Rivera claims that hospitals paid their doctors more based on how many “tubes they had tied” (Rivera 1). They categorized sterilizations as one of the few procedures their young physicians could perform, reminding physicians that, “everyone that you get to get her tubes tied means two tubes (i.e. an operation) for a resident or intern” (Rivera 1). They also pushed their young physicians to perform as many operations as possible. In the article, the overseeing physician is quoted as saying, “‘I want to congratulate the resident staff for 11 postpartum (after birth) tubal ligations last week.’ Another doctor responded, ‘They did even better last week. They did 15”’(Rivera 1).

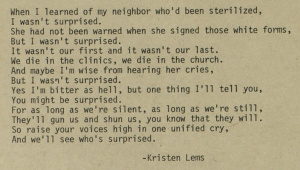

A poem by white folk artist Kristen Lems about an individual’s experience with a “neighbor who’d been sterilized” found in the Vol. 5 Issue 6 of the midwest periodical The Amazon published in 1977.

Incentivized by warped beliefs about poverty, money, and additional experience, medical professionals responded by developing systems to increase the number of sterilizations of minority women. These strategies often lead to procedures being performed without the patient’s consent. One common way doctors would trick their patients into receiving an abortion was by taking advantage of different levels of literacy. The Vol. 5 Issue 6 of the midwest periodical The Amazon exposes this method. Published in 1977, in the article “Women’s Union/ Sterilization Abuse” by Fai DeMark, white folk artist Kristen Lems’ poem reflects upon the speaker’s experience with a “neighbor who’d been sterilized” (DeMark 2).

When I learned of my neighbor who’d been sterilized

I wasn’t surprised.

She had not been warned when she signed those white forms,

but I wasn’t surprised.

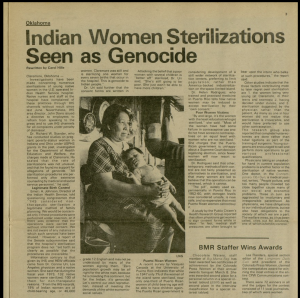

Published in 1975 in Vol. 3 Issue 3 of Big Mama Rag, the article “Indian Woman Sterilizations Seen as Genocide” looks into the impact of sterilizations on the population of an unnamed Native American Reservation in Oklahoma.

Lems repeats the phrase “wasn’t surprised” to indicate the prevalence and historical nature of the issue. Mass sterilizations have happened in the past and continue to disproportionately affect those who “had not been warned.” Often women of color did not know what they were agreeing to because they could not read the complicated medical jargon of “those white forms” (DeMark 2). Therefore, many women did not understand the procedure that was being performed. An example of the horrifying effects of this misinformation can be seen in Vol. 3 Issue 3 of Big Mama Rag, a Western Woman’s Journal. Published in 1975, the article “Indian Woman Sterilizations Seen as Genocide” looks into the impact of sterilizations on the population of an unnamed Native American Reservation in Oklahoma. The article finds that on this reservation, “one in four women did not realize the procedure [of sterilization] was irreversible and would have preferred to use a different form of contraception” (Hille 3).

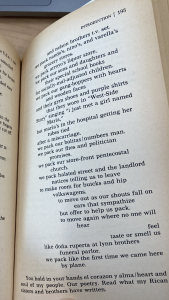

The forward “Puerto Ricans in the U.S.A.” by David Hernandez in the anthology From the belly of the shark explores the horror of the reality of sterilizations being performed after unrelated procedure.

Doctors also blackmailed women into getting sterilizations by withholding other forms of care if they did not agree to the procedure. Abortion, miscarriage, and even delivery were on the table. In the anthology From the Belly of the Shark, David Hernandez explores the horror of the reality of sterilizations being performed after an unrelated procedure in his forward “Puerto Ricans in the U.S.A.” In the forward, Hernandez chooses to write a poem, gifting the reader “el corazon y alma/heart and soul of my people. Our poetry,” (Hernandez 197). He begins each stanza with a “dream” which he then counters with the reality of “Chicago.” In one of the passages Hernandez first states the dream of “[settling] in a neighborhood with/ good stores, good schools,/ good hospitals and big tall churches” (Hernandez 197). The Puerto Rican-Americans are hoping for a community with a flourishing economy made up of “good stores”. They are looking for “big tall churches” that indicate hope and faith in the future. They are hoping for access to education through “good schools” and healthcare through “good hospitals.” Instead Chicago grants them a different reality. A reality that includes falling for a girl and “singing “i just met a girl named/ Maria” (Hernandez 197). Yet, then discovering that “maria’s in the hospital getting her/ tubes tied/ after a miscarriage.” The name Maria is at first capitalized, indicating that she has power and humanity. This is lost after she is forced to give up a part of herself through getting “her tubes tied.” She has lost a child through a “miscarriage” and then loses the chance to have any more. Maria went into the hospital for a “miscarriage” and receives a sterilization, a completely unrelated procedure. The dream was for a “good hospital” but instead the healthcare system takes advantage of her. Now, the community is not able to create the next generation, diminishing hope for the future. For the Chicana women in this community, the dream of a positive healthcare system is always out of reach. This poem reflects a growing movement of published literature by people of color about the horrors surrounding mass sterilization. Through various articles, poems, images, and letters, such authors began to raise awareness and helped articulate the centrality of a woman’s consent in reproductive decisions.

Works Cited:

DeMark, Fai. “Women’s Union/ Sterilization Abuse.” The Amazon 5, no. 6 p. 2

Hille, Carol. “Indian Woman Sterilizations Seen as Genocide.” Big Mama Rag 3, no. 3, April 1,1975, pp. 3

Hernandez, David . “Puerto Ricans in the U.S.A” From the Belly of the Shark : A New Anthology of Native Americans : Poems by Chicanos, Eskimos, Hawaiians, Indians, Puerto Ricans in the U.S.A., with Related Poems by Others. 1st Vintage Books ed. New York. 1973. pp. 193-197

Rivera, Gloria. “Sterilization: La Operacion/ The doctor may need it more than you!.” Triple Jeopardy, no. 3, January 1, 1974, pp. 1