Betty Friedan’s 1963 book, The Feminine Mystique, explores the idea of the “the problem that has no name” (48). Women across America felt the effects of this problem, but denied its existence or could not name it. They felt “empty somehow…incomplete” or as if they “don’t exist” (48). She explains how women were discouraged from working outside of the home after 1949. It was bad to want a career or education, because they were supposed to find life fulfillment in the domestic sphere as a “suburban housewife” (46). However, excerpts she included from domesticated women all contain an underlying theme: a feeling of emptiness, loss of personality, and incompleteness. Friedan coined this unnamed problem the “feminine mystique.” “The feminine mystique,” she explains, “says that the highest value and the only commitment for women is the fulfillment of their own femininity” (70). This was damaging to women, for they were encouraged to ignore the question of their identity in the name of a socially constructed feminine fulfillment. “Culture does not permit women to accept…their basic need to grow and fulfill their potentialities as human beings” (101).

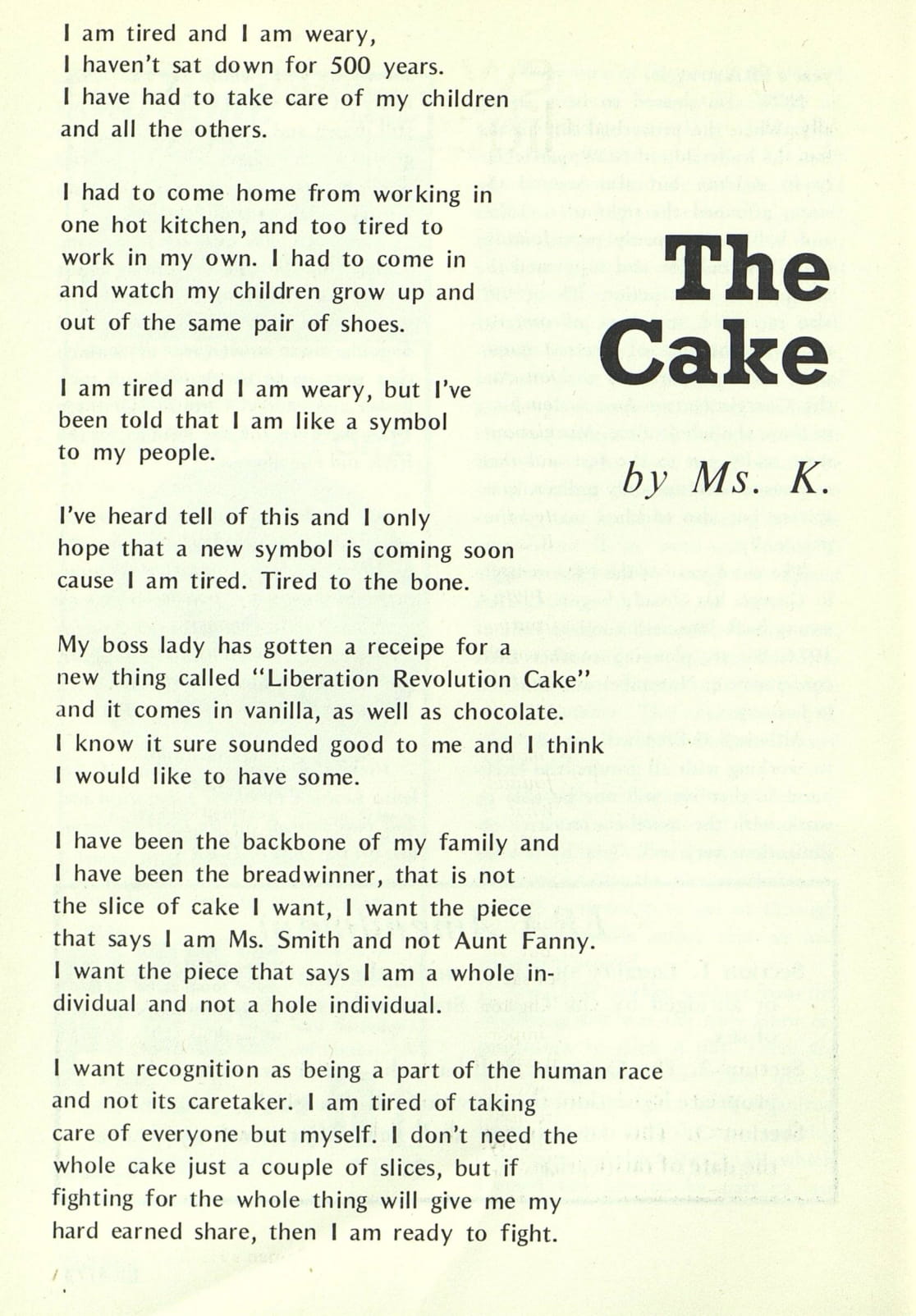

Women were expected to ignore their identity and find fulfillment in domestication. Living up to this expectation was tiring, and left women feeling incomplete and empty. Ms. K illustrates this in her poem “The Cake.” The woman in the poem is exhausted from taking care of her family and working. “I had to come home from working in / one hot kitchen, and too tired to / work in my own.” She further explains this in the seventh stanza, in which she says “I am tired of taking / care of everyone but myself.” Ms. K highlights the lack of recognition women receive for the work they do in and out of the house: “I want recognition as being a part of the human race / and not its caretaker.” Her poem calls attention to the repetitive and tiresome facade women participated in, in attempts to find feminine fulfillment.

However, culture was advancing because of the Women’s Liberation Movement. Women joined and emerged from fields previously dominated by white males. One prominent field for feminists was poetry. Women poets began publishing their work more, and many came together for poetry readings. The Poetry Foundation’s new podcast series, A Change of World, explores books, workshops, and poetry from the time to tell stories of how women formed communities during the Women’s Movement. In their episode “Shattering the Blue Velvet Chair,” Carolyn Forché discusses what she calls the Blue Velvet Chair occupied by women poets. She tells the interviewer that she came up with this label when looking at photographs of American poets. Most, if not all, the people in the photographs were white and male. If there was a woman, she would appear seated in a cushioned chair. It was her way of speaking to the tokenization of women poets during the time. However, women rejected this tokenization, and instead turned to poetry as a way to define culture outside the boundaries imposed on them.

In challenging and changing those boundaries, many women broke out of the cage of domesticity and began to fight for workplace equality. It became more acceptable for women to work and have careers, rather than solely finding fulfillment in being a housewife. This process of change in working social norms eventually led to legal protections. President John F. Kennedy signed the Equal Pay Act of 1963, which prohibited sex-based wage discrimination between men and women in the same place of work who do the same job that require the same skill, effort, and responsibility. One year later, Title VII, as part of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson, which prohibited employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex and national origin.