Women across the nation in the early 20th century were portrayed as weak and in need of a man to swoop in and save them from themselves and the potential “harms” of working, education, and participating in other social spheres. They were sheltered in order to keep them pure and innocent. However, this instead kept them compliant to men’s every desire. They were to exist only for and through their husband and children, as Betty Friedan noted in her groundbreaking study The Feminine Mystique (Friedan, 74). Second wave feminists sought to change that, and fought to liberate women by empowering them.

A basic dictionary definition will tell you that power is the “possession of control, authority, or influence over others” (Power). Women in the 1960s and 1970s pursued power through having control and influence over themselves. This was a struggle, for it was not easy to break past the cookie cutter molds assigned to them. As Nancy MacLean notes in her introduction to the American Women’s Movement, “Collectively, their action showed that the debate was no longer over whether women should participate in public life but over how and towards what ends” (MacLean, 4-5). The power and strength it took women to free themselves from those roles liberated them from continuation in a system that treated them as fragile. Some women did this through self love and body positivity (Processes, 60). Others accomplished this by working outside the home or writing poetry. Poetry was a powerful tool for women in the second wave. “The inner lives of women came into language during that crucial decade and a half, as manifested in poems… because in the process of speaking what was hidden, we began to identify with one another as women, to become a ‘we’” (Moore, xv-xvi). Audre Lorde’s essay “Poetry Is Not A Luxury” speaks to the invaluable tool it is for women:

For women, then, poetry is not a luxury. It is a vital necessity of our existence. It forms the quality of the light within which we predicate our hopes and dreams toward survival and change, first made into language, then into idea, then into more tangible action. Poetry is the way we help give name to the nameless so it can be thought. The farthest horizons of our hopes and fears are cobbled by our poems, carved from the rock experiences of our daily lives. (Lorde, 37)

Many poets used that medium to talk about the struggles they and other women faced in everyday life.

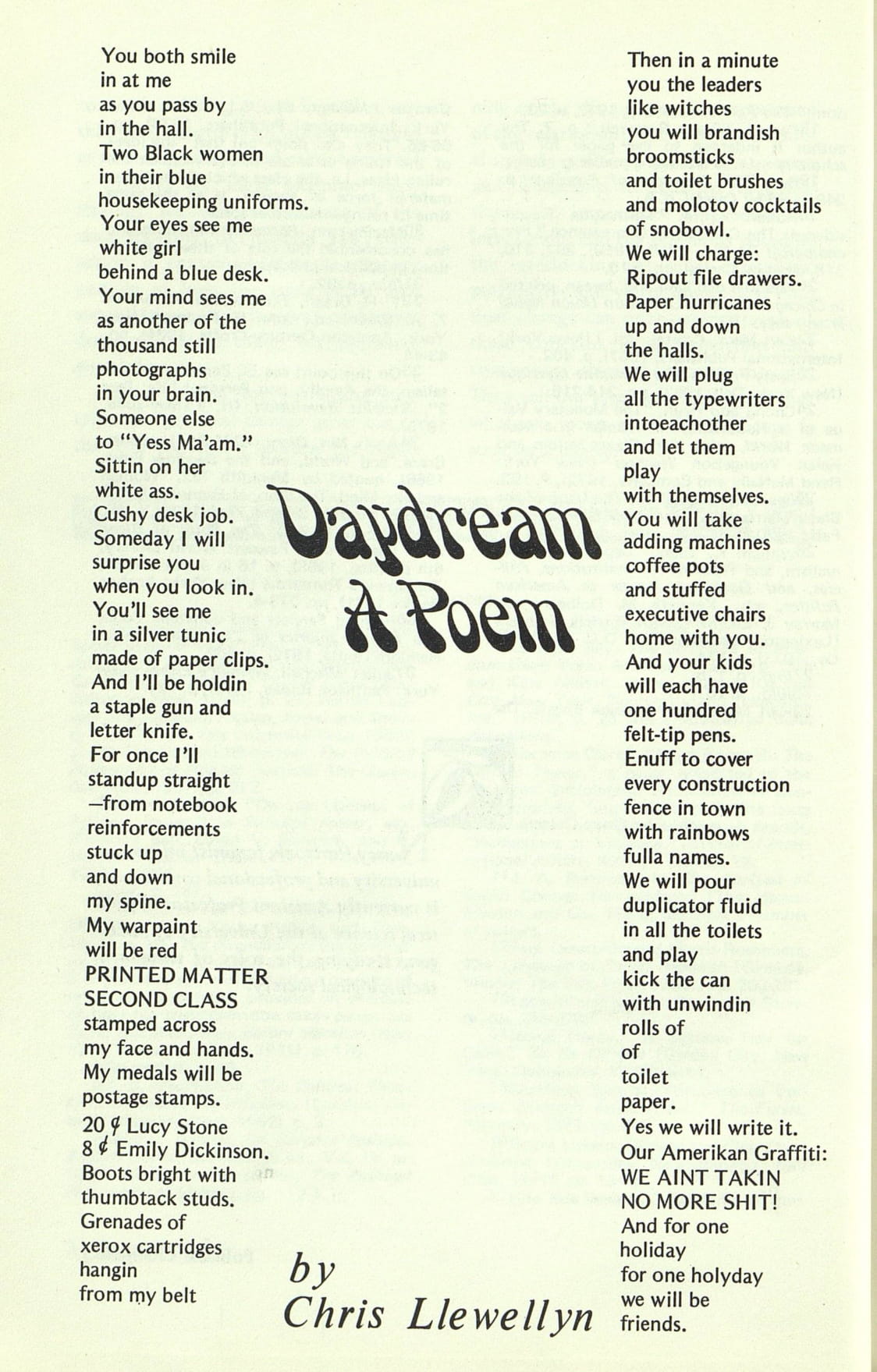

In her poem, “Daydream A Poem,” Chris Llewellyn addresses this shift by painting women as warriors, fighting for women’s rights. She begins her poem with an encounter between two housekeepers and a secretary. There is tension between the women, for the secretary is seen as someone with just a “cushy desk job.” She continues by saying she will surprise them by becoming a warrior in lines 24-36. Throughout the poem, the three women band together in this fight. The placement of the scene in an office (specifically in the area of a desk where a secretary might sit) speaks to the types of jobs that women commonly were allowed to hold. By the end of the poem, Llewellyn seems to grow tired of this positioning of herself and other women: “Yes we will write it. / Our Amerikan Graffiti: / WE AINT TAKIN / NO MORE SHIT!” Her poem empowers the women in it, and portrays them as everything except weak. They band together to fight the injustices they face in the world.

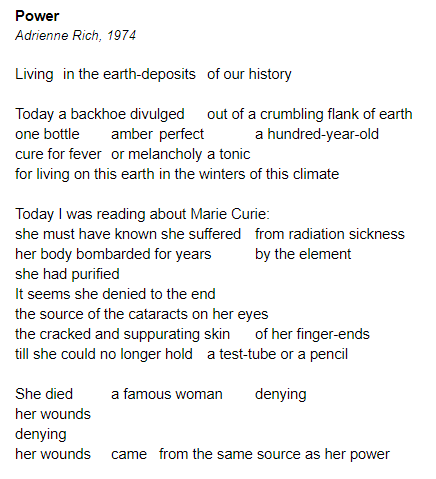

Adrienne Rich further illustrates women’s strength in her poem “Power.” Rich tells the story of Marie Curie, a scientist who conducted research on radioactivity. She was the first woman to win two Nobel Prizes for her work in both physics and chemistry. Curie risked her life to continue her research, which was the “same source as her power.” Curie’s story speaks volumes about the courage and devotion of women throughout history in their continuous pursuit of what they believe in. Rich illustrates this in lines 7-9: “she must have known she suffered from radiation sickness / her body bombarded for years by the element / she had purified.” Her word choice in this poem paints a picture of importance of Marie Curie and her accomplishments.