Robin Morgan’s “Arraignment” as it was published in 1972 in The Feminist Art Journal.

Robin Morgan’s “Arraignment” was originally published in her book Monster in November 1972. Morgan wrote the poem in response to the death of the well-known feminist poet Sylvia Plath. Plath committed suicide in 1963. Her suicide occurred after a lifetime of mental health struggles and also, importantly, after her husband, Ted Hughes, left her for another woman. “Arraignment” became a symbol for the feminist movement, republished in periodicals all over the country.

Morgan’s poem is an accusation. The poem’s title refers to charges being read to a defendant in court. In the first stanza of the poem, it becomes very clear what these charges are. Morgan states “I accuse / Ted Hughes / of … the murder of Sylvia Plath,” and later “real blood on real hands,” leaving no room for question about who she feels is to blame for Plath’s death (Morgan 4). Morgan also makes sure to emphasize within this first stanza that she feels Hughes’ role in Plath’s death has been covered up to a certain degree. She states that Hughes’ “murder” is something that “the entire British and American / literary and critical establishment / has been at great lengths to deny” (Morgan 4). This inclusion is pertinent because it shows how Morgan’s choice to write about Hughes in a negative light is going against popular media at the time; she is choosing to call out a man to whom the rest of the world appears to have turned a blind eye. Morgan’s choice to speak out when no one else did highlights her direct approach to attacking the issue of domestic violence.

An important clarification is that Morgan is not accusing Hughes of physically murdering Plath. Plath’s death by suicide occurred after she had separated from Hughes; she had physically moved apartments away from him with her two children and was alone when she ultimately ended her life. Rather, Morgan implies that Hughes’ abuse throughout their marriage contributed to Plath’s mental illness and eventual suicide. In her second stanza, she makes this explicitly clear, proclaiming “not that it isn’t enough to condemn him / of mind-rape and body-rape” (Morgan 4). Here, Morgan alludes to both physical and emotional assaults on Plath by Hughes. She insinuates that even if Plath had not killed herself, Hughes would be a villain solely for his behavior in their marriage. The Guardian published an article in 2017 supporting Morgan’s claims of Hughes’ abuse; the article brings to light recently found letters between Plath and her therapist in which she states that Hughes beat her before she miscarried their child and “wanted her dead” (Kean). The context of Morgan’s argument running parallel to Plath’s is important because it gives more validity to “Arraignment” in that Morgan is not speaking for Plath so much as amplifying statements Plath already made. Thus, a big part of Morgan’s role in pushing back against domestic violence is through a type of elevation of female victims’ voices and a refusal to be intimidated by the fact that no one else seemed to be speaking up for Plath.

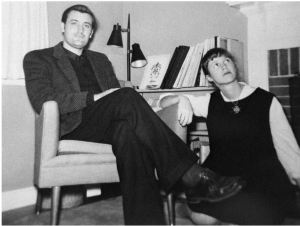

A photo of Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes. This image is from the Boston Globe article “The Last Days of Sylvia Plath.”

Morgan goes on to accuse Hughes of not only crimes of domestic violence, causing Plath’s death, but also “hiding of her most revealing indictments / against her jailor” (Morgan 4). The inclusion of the word “jailor” in reference to Hughes refers to Plath’s poem “The Jailor” which discusses an abusive relationship through the metaphor of a prisoner and a jailor. Furthermore, after Plath’s death, Hughes was given the rights to her work due to their still technical status as a married couple even though they had been separated. So, what Morgan is referring to in the quotation is that because Hughes had the rights to Plath’s body of work, he also had the power to remove or refuse to publish certain aspects of it in a self-serving way. For example, according to Sady Doyle’s in her book Trainwreck “her journals were released–but Hughes admitted to burning or losing the ones from the last months of her life and the edited ones were full of [OMISSION] marks” (Doyle). So, Morgan is making the claim that the journals which Hughes admitted to destroying likely contained more evidence of his abuse. The line “and making a mint by becoming her posthumous editor” refers specifically to the omission marks aforementioned (Morgan 4). Morgan is portraying Hughes as not only an abuser but also someone who attempted to leech off of his victim after causing her death–the ultimate villain. Through demonizing Hughes to the degree that she does, Morgan successfully fights back against a culture that previously failed to condemn domestic violence, a culture that assumes male superiority and turns a blind eye to injustices. She makes an example of Hughes through the statement that she will not allow his crimes to go unnoticed or unpunished.

Morgan’s poem does not focus solely on Plath, a very well-known figure, but also seeks to bring justice to Hughes’ second wife, Assia Guttmin Wevil. She states “and / if he’s killed one wife / he’s also killed two / the second, also, committed suicide” (Morgan 4). Her choice to include Wevil’s story makes her argument against Hughes more powerful because it highlights Hughes as a common denominator in two cases of extreme mental illness to the point of death. She sarcastically states “what a coincidence,” in reference to both of his wives committing suicide, underscoring her earlier assertions of Hughes as abusive by implying that these events could not be coincidental (Morgan 4).

Morgan’s poem was especially effective in outing Hughes as a villain because her poem was aggressive enough to cause him to sue her (Doyle). She anticipated this, ending her poem with “in the meantime, Hughes / sue me,” making the fact that Hughes actually did sue her almost comical; she anticipated his very move and therefore he essentially played into her hands (Morgan 4). Hughes sued in an attempt to not let the poem be seen but his choice had the opposite effect. Feminist periodicals all over the country started to publish the poem as a result because they felt that Hughes’ attempt to cover it up was further evidence of the truth in the accusations of abuse it contains.

Morgan’s bold choice to call out Hughes directly is symbolic of a larger statement. She refuses to allow victims of domestic violence to be ignored; in an originally somewhat solitary stance, she highlights the power of the individual voice. Morgan’s poem began as her own statement on domestic violence and abuse and grew to become a part of the larger feminist movement.

Sources:

Doyle, Sady. Trainwreck. Melville House, 2016.

Kean, Danuta. “Unseen Sylvia Plath letters claim domestic abuse by Ted Hughes.” The Guardian, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/apr/11/unseen-sylvia-plath-letters-claim-domestic-abuse-by-ted-hughes. Accessed December 2021.

Morgan, Robin. “Arraignment III.” The Feminist Art Journal, vol. 1, p. 4.

Morgan, Robin. “Arraignment III.” The Spokeswoman, vol. 3, p. 5

Rollyson, Carl. “The Last Days of Sylvia Plath.” The Boston Globe, 2013. https://www.bostonglobe.com/magazine/2013/01/20/the-last-days-sylvia-plath/Dlpv1hzF4OFO6gtxoGNG5I/story.html. Accessed December 2021.

The Feminist Art Journal, vol. 1, Issue 2, September 1972

The Spokeswoman, vol. 3, Issue 6, December 1972