Winona LaDuke posits in her interview “They Always Come Back” that “Native peoples have become marked as inherently violable through a process of sexual colonization. By extension, their lands and territories have become marked as violable as well. The connection between the colonization of Native people’s bodies– particularly Native women’s bodies– and Native lands is not simply metaphorical” (55). The oppression of Indigenous peoples is connected to the exploitation of the earth. With each generation, the capitalist system demands more resources from the land, “first for agricultural crops, then for gold, then for iron, then for oil, and now uranium” (LaDuke 53). Because Indigenous people live in balance with the earth, their fate is directly related to the fate of the earth. There is an apparent historical trend in the subjugation of Natives, which like the desecration of natural ecosystems, can be traced back to the colonization of the “New World” centuries ago. The genocide of Indigenous peoples is systemic in the “development” of the “civilized” world. White Americans view the development of their society as “a mastery of the natural world, a prime example of the progress from primitive to civilized society,” without taking into consideration that their society is not immune to surviving ecological disasters of their own making. (LaDuke 57).

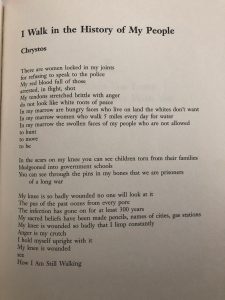

“I Walk in the History of My People,” as printed in the fourth edition of This Bridge Called My Back.

Published in all four editions of the feminist anthology This Bridge Called My Back, the poem “I Walk in the History of My People” by Native American writer Chrystos articulates how she carries the intergenerational trauma of her community within her flesh and blood. In the first stanza, the speaker illustrates the suffering of Native American women, which resides within her physical body. For example, there are “women locked inside [her] joints / for refusing to speak to the police,” referencing the historical sexual violence inflicted by white patriarchs in positions of power and Indigenous women’s refusal to cooperate with the same government entity that ignores the systematic abuse of Native women. In the first stanza, the speaker implements anaphora to describe how “in [her] marrow are hungry faces who live on land the whites don’t want,” alluding to how Native Americans are displaced within their own homeland. Within her marrow are also the faces of her people who are “not allowed / to hunt / to move / to be” because of the ongoing genocide of Indigenous people committed by the U.S. settler-colonial project through dispossession of their ancestral territory and the mass extermination of their sustenance, forcing them to become dependent on the very same state that is murdering them. For instance, the once great bison herds, a staple of the Great Plains indigenous peoples, were purposefully hunted to the precipice of extinction by the U.S. government. Without the bison, which they depended upon to survive, Native American nations became crippled and were forced to rely on the government to provide rations so as to not starve. In addition, Native Americans were prohibited from hunting for sustenance, limiting them from exercising autonomy in their rightful territory.

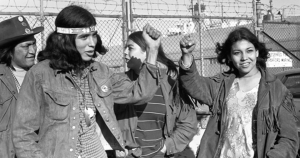

February 27, 1973: Activists occupy Wounded Knee.

In the scars on her knee, one can see “children torn from their families / bludgeoned into government schools,” referring to the forced assimilation of Indigenous youth at the hands of the American educational system. By severing them from the umbilical cord of their Indigenous families, the youth forgot their native tongue and underwent cultural genocide as generations upon generations of Indigenous knowledge was erased. For at least three hundred years, the infection of white supremacist, patriarchal settler-colonialism has been festering in the knees of the Native American. The speaker’s infected knee is a historical allusion to the Wounded Knee Massacre, the state-sanctioned slaughter of nearly three hundred Lakota people by the United States Army in 1890. Nearly a century later, in the Wounded Knee Occupation in 1973, the American Indian Movement resisted colonial violence by protesting the United States government’s failure to fulfill treaties with Native American nations and by demanding treaty negotiations to ensure equitable treatment of their people and lands. In their “respective struggles for survival, the Native peoples [were] waging a war to protect the land, the water, and life, while the [colonial] culture [strove] to protect its murderous lifeblood” (LaDuke 56). Although the militant insurrection was ultimately disbanded, despite centuries upon centuries of genocide, Native Americans are still walking upright in an age where they are not meant to survive.

Sources:

“AIM Occupation of Wounded Knee Begins.” History, 9 February 2010, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/aim-occupation-of-wounded-knee-begins. Accessed 4 December 2021.

Anzaldúa, Gloria, and Moraga, Cherríe, editors. This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color. 4th ed., State University of New York Press, 2015.

Chrystos. “I Walk in the History of My People.” Anzaldúa, Gloria, and Moraga, Cherríe, editors. This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color. 4th ed., State University of New York Press, 2015.

LaDuke, Winona. “They Always Come Back.” Sinister Wisdom, no. 22-23, pp. 52-57.