Printed in all four editions of This Bridge Called My Back, beginning in 1981, Jo Carrillo’s “And When You Leave, Take Your Pictures With You” exemplifies the tension between Third World and white feminists as they search for a common movement. The speaker condemns “Our white sisters/ radical friends” who “love to own pictures of us”—who love to own pictures of Third World women (4th ed., lines 1-2, 3). Although the speaker does not directly address these white feminists in the body of the poem, she does directly address them in the title: “And When You Leave, Take Your Pictures With You,” the speaker calls out, as if dividing assets after a divorce, as if expelling white women from the feminist movement she reclaims.

Although these white women are the speaker’s “sisters,” they manipulate the physical bodies of women of color through trapping them in their picture frames (1). These women remain frozen, locked in frames, forever “holding brown yellow black red children / reading books from literacy campaigns / holding machine guns bayonets bombs knives” (7-9). Here, the speaker groups together the “brown yellow black red children,” not separated by commas or punctuation of any kind, to demonstrate that many white feminists view these children as one unified group, ignoring their diverse histories and origins (7). Similarly, the speaker continues to show the implicit prejudices of these women, who keep photographs of women “with straw hat on head if brown / bandana if black” (18-19). Again, all “brown” and “black” women are grouped together: women of color, and their hats and appearances, must fit these white womens’ stereotypes in order to warrant a spot on their walls (18-19).

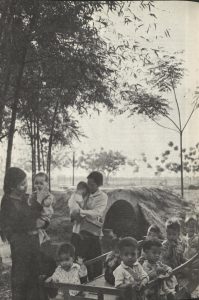

Up From Under also uses photographs of Third World women in this way. In the 1970 and 1971 publications of Up From Under, Vietnamese women tend to their “brown yellow black red children” in the “fields in hot sun” (7, 17). They cradle these children—many of them not their own—against the pockmarked, war-torn ruins that lie behind them.

From Up From Under, vol. 1, no. 2.

From Up From Under, vol. 1, no. 4 (p. 11).

Likewise, an image of two Vietnamese women “holding…bayonets” takes up almost an entire page of Up From Under, vol. 1, no. 2 (9). Dressed in formal military attire, but walking barefoot on a beach, they seem ready to enter battle and yet oddly relaxed.

From Up From Under, vol. 1, no. 2 (p. 54).

Printed in a periodical created by and about American white women, these images enter the memories—the mental picture frames—of white readers across America. Although white readers might gladly glance at these photographs, or hold them in their hands and own them when they buy a copy of Up From Under, when Third World women appear “in the flesh / not as a picture they own, / they are not quite as sure / if / they like us as much” (4-38). As the speaker concludes, “We’re not as happy as we look / on / their / wall” (39-42). In describing “their / wall”—a singular wall—the speaker groups together white women, who remain perpetually in contrast with an undefined “we”: the Third World women who exist only in their pictures. The speaker suggests that these two groupings of women should separate. One principal question drives this poem: can Third World and white feminists ever unite and build a shared community?

Sources:

Anzaldúa, Gloria, and Moraga, Cherríe, editors. This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color. 4th ed., State University of New York Press, 2015.

Carrillo, Jo. “And When You Leave, Take Your Pictures With You.” Anzaldúa, Gloria, and Moraga, Cherríe, editors. This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color. 4th ed., State University of New York Press, 2015.

Up From Under, vol. 1, no. 2, August 1970.

Up From Under, vol. 1, no. 4, 1971.