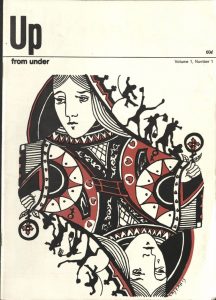

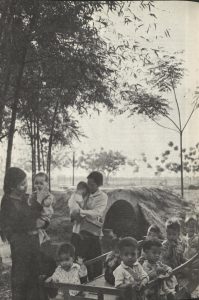

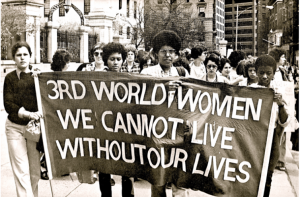

In her preface to the fourth edition of This Bridge Called My Back, Cherríe Moraga, Chicana writer and feminist, announces: “We are ‘third world’ consciousness within the first world. We are…in concert with women across the globe pursuing the same goals: a shared and thriving existence in a world where our leaders have for the most part abandoned us and on a planet on the brink of utter abandonment” (xix-xx). In an article entitled “The Winter Soldier,” on American soldiers in the Vietnam War printed in Up From Under, an anonymous writer declares, “The people dying are Third World, and that has to be brought out” (9). Both Cherríe Moraga, in 2015, and this anonymous writer, in 1971, struggle to define “Third World women”—a term that shaped the Feminist Poetry Movement in the last third of the twentieth century.

The fourth and most recent edition of This Bridge Called My Back, published in 2015.

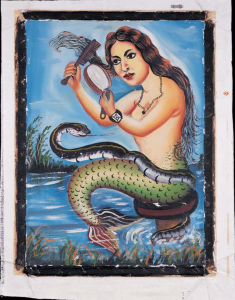

The first edition of This Bridge Called My Back, published in 1981.

This term divides the world into three distinct categories. “Third World,” as defined by the Oxford English Dictionary, refers to “The countries of the world, esp. those of Africa and Asia, which are aligned with neither the Communist nor the non-Communist bloc; hence, the underdeveloped or poorer countries of the world, usually those of Africa, Asia, and Latin America” (“Third World”). In “Third World,” ideas about race, wealth, colonialism, imperialism, and origin intertwine. Today, in 2019, this term has largely become as obsolete as Cold War Blocs, and is often replaced with the phrase “developing countries.” However, many Second Wave feminists used Third World to describe women of color in America, emphasizing their lasting connection to countries outside of America (Mohanty, Russo, Torres).

To many white feminists, Third World signaled a perpetual “other”: countries and people who lacked resources, education, and wealth. Nevertheless, Third World feminists focused on the perseverance of Third World women in the face of oppression and used this term to express solidarity with women of color around the world. The tension between these usages informs our modern interpretation of the Feminist Poetry Movement.

Up From Under, vol. 1, no. 4, published in 1971.

Sources:

Anzaldúa, Gloria, and Moraga, Cherríe, editors. This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color. 1st ed., Persephone Press, 1981.

Anzaldúa, Gloria, and Moraga, Cherríe, editors. This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color. 4th ed., State University of New York Press, 2015.

Mohanty, Chandra Talpade, Russo, Ann, and Torres, Lourdes, editors. Third World Women and the Politics of Feminism. Indiana University Press, 1991.

“Third World | third world, n. (and adj.).” OED Online, Oxford University Press, September 2019, www.oed.com/view/Entry/200854. Accessed 20 November 2019.

Up From Under, vol. 1, no. 4, 1971.