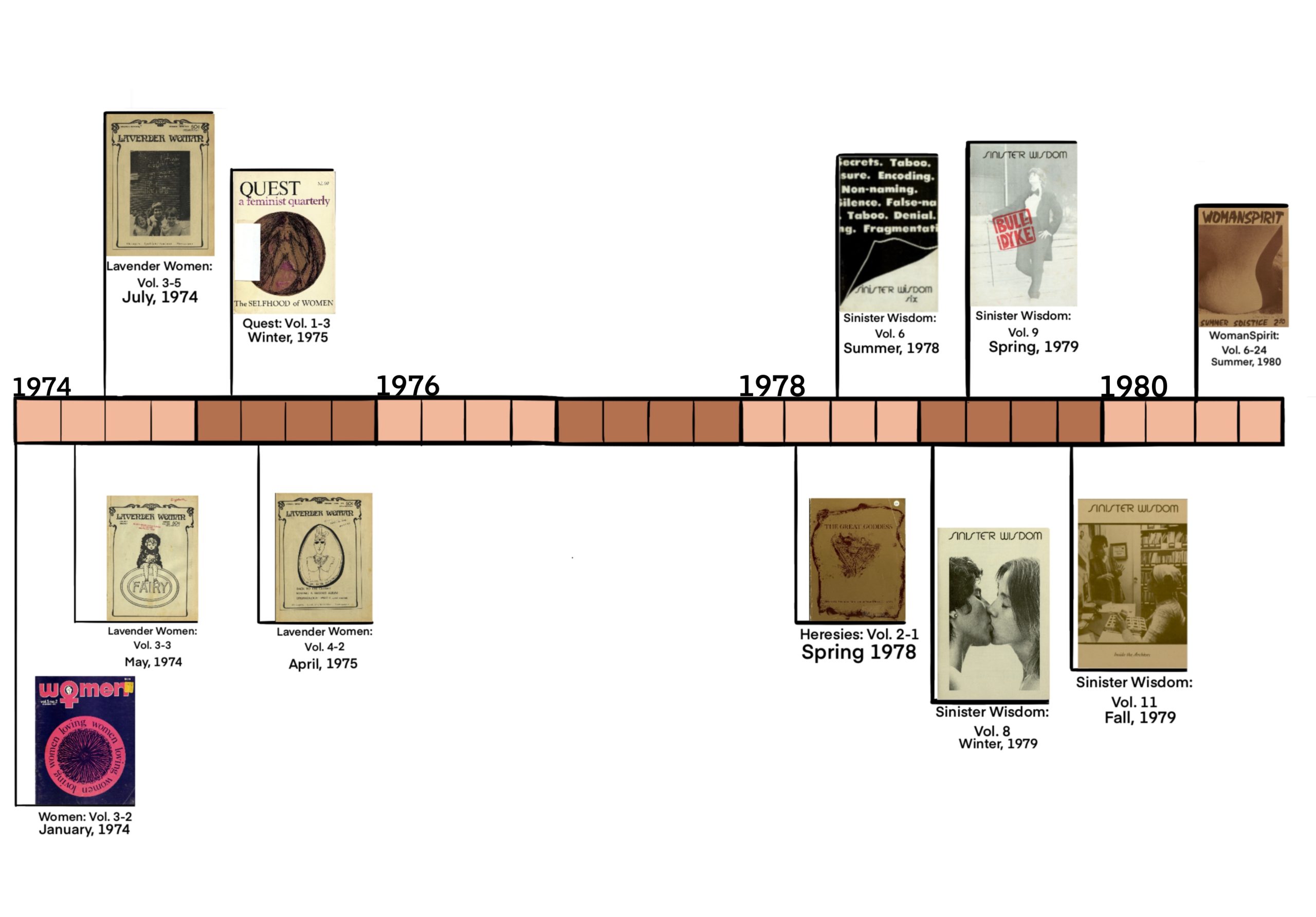

Martha Courtot first featured the poem, “This is trying not to be a love poem,” in a 1974 issue of Women: A Journal of Liberation. Up until the 1980’s, Courtot proceeded to publish in various periodicals; including, Lavender Woman, Heresies, WomanSpirit, and Sinister Wisdom.

Timeline of some of Martha Courtot’s publications in Feminist periodicals: 1974-1980

Sampling her poems from various periodicals, it is evident that Courtot often focuses on women’s relationship with nature. Some of her poems following this pattern are “the snake woman,” which was featured in Sinister Wisdom’s sixth issue, and “The Woman Who Lives with Owls,” in Sinister Wisdom’s ninth issue. In these two poems, Courtot explores the idea of women finding their true identities.

At the start of “the snake woman,” Courtot details all the ways in which this snake woman is undesirable. “She is a snake woman / she has no eyelids / she wears the skin of dead animals” (Courtot, “Snake Woman,” lines 1-3) and she hides from the light. But Courtot ends the poem with,

this woman is bad

her name begins with your initials

her face is very familiar

this woman moves the way your body does

crawling toward morning

do you know this woman?

do you know her?

do you know? (Courtot, “Snake Woman,” lines 35-42)

This sequence of questions pushes the reader to look below their own skin, to find their dark insides, and to truly come to terms with it no matter how disfigured it may be. In “The Woman Who Lives with Owls,” Courtot equates women to nature once again, but this time to illustrate how society is deaf to the female voice.

The woman who lives with the owls speaks with the birds, learning the intricacies and secrets of the owl language, a metaphor for a woman’s connection to nature and the primal. However, when the woman transcribes what the owls have taught her she attempts to share her findings with the world. But, “no one will look her in the eye / they claim she writes like everyone else / on white paper and sends them through the mail,” highlighting the prominence of sexism in publishing at the time (Courtot, “The Woman Who Lives With Owls,” lines 10-13). Eventually, the woman who lives with owls becomes the owl woman, secluded in nature away from the society that refused to hear her. The owl woman is happy in her new state, suggesting that the modern woman can find joy in her craft regardless of whether the society she lives in can properly appreciate it.