Holly Lu Conant first published a poem in Sinister Wisdom’s Spring 1977 issue. The issue focused on the relationship between mothers and daughters, including various photographs, personal essays, and poems. Conant submitted a poem called “disunited nations,” which explores the relationship between Mother Earth and Native Americans.

In the poem, Conant explores the extent to which the colonists violated the American continent, detailing how they “landed on my body / planted flags between my breasts / charted trade routes and highways across my belly” (Conant, “disunited nations,” lines 1-3).

Her diction indicates a distinct tone of desecration and mutilation of the beauty of Mother Nature. But Mother Nature is protective and declares, “ALL COLONISTS WILL BE REPATRIATED / this is the motherland / I will not be settled” (Conant, “disunited nations,” lines 11-13), and in this declaration the motherland establishes her conviction to resist the colonial influence that directly harms the Native American people who are, by extension, her children.

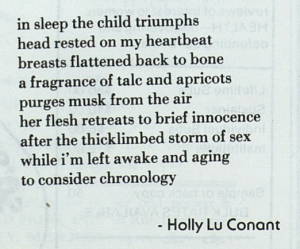

Holly Lu Conant’s untitled poem. Featured in Sinister Wisdom vol. 5, page 80.

And so, in this poem Conant steps outside the immediate impression of what a mother-daughter relationship is, and elevates it to a greater level. She accomplishes something similar in her second poem, published in Sinister Wisdom’s fifth issue (winter 1978). In her untitled poem, Conant focuses on the sound of silence. The poem begins with a child in sleep, and ends with the speaker stunned and contemplative. However, the lines between are rich with sensory language and imagery, suggesting that even in silence a powerful message can be conveyed. This seems to contradict the focus of Sinister Wisdom’s fifth issue. The issue aimed to counteract social deafness and amply women’s voices. But Conant’s poem focuses so heavily on silence, that it actually rings louder than words. By focusing on the silence, Conant’s piece highlights the importance of everything that women do not say, keeping in line with the theme of the periodical. In this way, Conant stepped outside the expected to illustrate the theme, the same way she did in “disunited nations”.

We could infer that this unconventional presentation is simply Conant’s artistic style, but these appear to be the only two poems published by Conant. Even though Conant describes herself as, “born 22 years ago, am not dead yet & am writing furiously in between,” her other pieces never seemed to make it to print (Desmoines and Nicholson, “Contributors”, p103). Thus is the nature of the press culture during the Feminist Movement. Even though the platform provided opportunity for expression and many women did utilize it, not every woman found a future in press and literature, though their words are immortalized in the record.