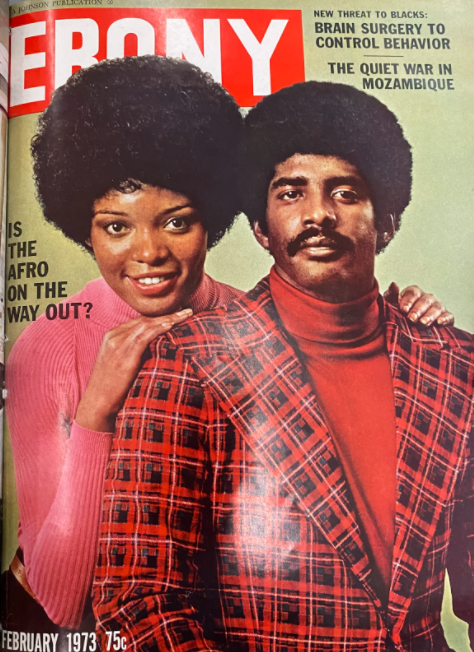

Front cover of Ebony Magazine issue from February 1973. The mainstream journal is geared toward African Americans. Pictured are a man and a woman, both wearing afros, and a headline that asks “is the afro on the way out?”

European beauty standards were also imposed on black women, evident in the February 1973 of Ebony, a mainstream journal that catered to African Americans. The question “is the afro on the way out?” on the cover of the issue drew attention away from the significance of the afro, which was “a hairstyle [that] quickly emerged as a symbol for Black beauty, liberation and pride” (Ebony, Vaughns). It dismissed the natural African American hair texture as a trend that needed to be moved on from. This issue came out long after the start of the Black is Beautiful movement, which began in the 1960s, where women began to actively resist the European standards they had been subjugated to, and embraced their natural hair texture (Vaughns). Ebony Magazine took the first opportunity they had in the 1970s to draw people away from the afro. Only later in the decade did the afro actually lose some momentum when braids and cornrows received attention, but it wasn’t until the 1980s and 1990s that those hairstyles replaced the afro entirely (Vaughns).

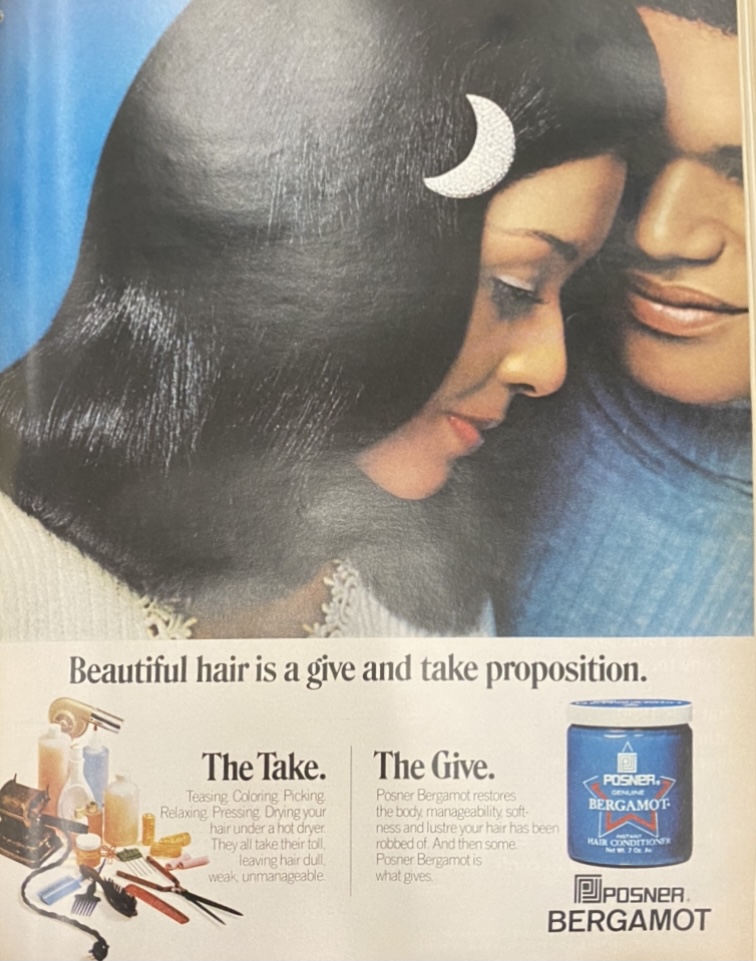

“Beautiful Hair Is a Give and Take Proposition” advertisement in the same February 1973 issue of Ebony. The advertisement is sponsored by Posner Bergamot, a haircare line for African Americans, and shows a woman’s straight, ironed hair as the result of using the product.

This 1973 issue of Ebony undid some of the progress made by the Black is Beautiful movement by reverting to the straightened hair standard despite the introduction of braids. For instance, the page from the issue shows a light-skinned black woman with processed, ironed, almost doll-like hair. This feature is inherently European, since African Americans typically have thick, curly, and voluminous hair. Under the image reads, “beautiful hair is a give and take proposition,” which makes a bold generalization of what beautiful hair constitutes. The “give and take” line implies that a black woman’s natural curls need to be effortfully worked on in order to attain unnatural straight hair that looks like that of a white woman. In the image, a man is embracing the woman and providing his validation of her beauty, suggesting that if black women want to be appealing to men, they must alter their natural features. The colonialism and sexism that motivate the beauty standards subjugates black women to a constant feeling of inferiority and need for improvement.

Works Cited

Vaughns, Victor. “The History of the Afro.” EBONY, 17 Dec. 2018, https://www.ebony.com/style/the-history-of-the-afro/.

Ebony, Johnson Publishing Company, Inc. Feb. 1973, pp. cover, 8.