Irena Klepfisz emphasizes intergenerational connection in feminist Judaism in her bilingual poem “Di Rayze Aheym/The Journey Home.” Appearing in “The Tribe of Dina” in the section “My Ancestors Speak,” Klepfisz balances the language of her Polish-Jewish heritage and her American upbringing, writing each line of the poem first in Yiddish and repeating them literally in English. Klepfisz, a child survivor of the Warsaw Ghetto in Nazi-occupied Poland, entered the United States as a young girl.

Irena Klepfisz in 1984

In the poem, she explores the idea of a stationary home with her childhood as a traveling refugee. Klepfisz struggles with the idea of a “native” language, as she was born into a Polish-speaking family, adopted Yiddish in the Ghetto, and English when she immigrated. Klepfisz uses this poem to explore “the history / of the war / of the peace / of the survivors / among strangers / on this side” (53). In these lines, she chronicles her own experience of the Holocaust: first war, then peace in America, then the experience of a refugee, growing up in a new place with a new language, and feeling partitioned from her homeland and community. She specifically documents her confusion and loss: “Whom can I speak to? / even the ghosts / do not understand me” (54).

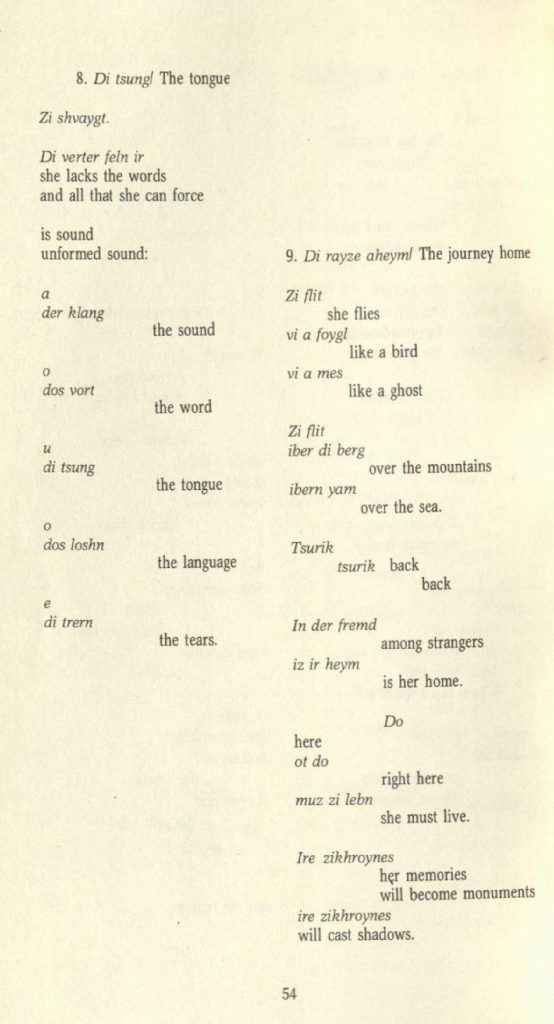

The final section of “Di Rayze Aheym/The Journey Home.”

Klepfisz closes the poem with a statement of hope, declaring in the third person that “her memories / will become monuments / will cast shadows” (54). Here Klepfisz employs the Jewish principle of generational learning; she acknowledges that her pain will become power for the next generation.

The transmutation of female Jewish trauma turned into power as seen in “Di Rayze Aheym/The Journey Home” is emphasized in the next section of the periodical, “The Women on Our Family.” The title of the chapter appears on the opposite page of the poem, and the section contains a series of recorded oral histories by Jewish families in both prose narratives and poems. Ruth Whitman’s poem “Bubba Esther, 1888” (94) relays a conversation in which her grandmother (in Yiddish, “bubba”) reveals that she was sexually assaulted as a young girl while immigrating to the United States. This poem, unique in its temporal and spatial setting of nineteenth century Hamburg (94), conveys the universal female and immigrant trauma of sexual assault. As the grandmother imparts the horrific account, the speaker recognizes that “she wanted to tell me” (line 2) and she “was trying to tell me, / trembling, weeping with anger” (lines 25-26). The grandmother overcomes her anger and shame with great difficulty to tell her story and pass the story on to her granddaughter. For both women, the power of sharing the story and the lessons learned overwhelm the pain. Similarly, in Jennifer Krebs’ poem “Short Black Hair” (102), the speaker collects an oral history about her great aunt who died in the Holocaust. The speaker discovers the horrific violence of her great aunt’s victimization, and learns that her family abandoned her aunt because they could not afford to take the woman–left disabled by lobotomy performed under Nazi leadership–with them to America. The speaker reflects on this through her memories of caring for a disabled woman as a part-time job in college. The speaker connects with her ancestor based on what Sinister Wisdom founder Catherine Nicholson describes as “boundary status”–that is, those who are marginal to society. Both women are likely homosexual, interacted with disabled people or were disabled themselves, non-gender conforming, and operate outside the traditional conception of Jewish womanhood. The end of the poem concludes with the speaker’s commitment to keep cutting her hair, like Adele’s, as an act of solidarity and self-expression. She notes that Adele was a writer, and on the opposite page is a copy of the only surviving poem that Adele composed. Through this poem, the speaker forges an indirect but potent connection with her persecuted and wounded Jewish ancestor from which she draws resolve to keep pushing the boundaries of gender and culture.