In the first issue of the lesser-known radical Jewish feminist periodical Shifra, Liane Aukin’s poem “The Jewish Feminist Woman” explicitly defines Jewish feminism and Jewish womanhood as a product of generational trauma. In writing that “Being a jewish woman means / ….the terrible history of your forebears. / It means / you’re the sister, daughter, wife and mother / of men who are oppressed” (lines 28-34), Aukin lays out a model of Jewish womanhood that is created by the past and present oppression of Jewish men. Aukin is expressing similar sentiments to those of Irena Klepfisz and others in “The Tribe of Dina,” but her poem takes a decidedly radical turn. In Aukin’s poem, located on the page after the editorial statement, she writes about “resenting Zionism because / it produces a conflict of loyalties” (51-52) and “remembering / bagels and cheese / are a ball and chain / and my sister in Morocco / has never heard of Kvetches” (124-128). Both of these statements reflect the way Aukin relates Jewish feminism to other social justice movements, such as the desire for peace in the Middle East and “Third World Feminism” expressed by the recognition of the shared oppression of both Western and non-Western women. While noting that the expectation that Western Jewish women are housekeepers is oppressive (“bagels and cheese / are a ball and chain”), Aukin makes sure to dually recognize that her “sisters” in the non-Western world are faced with different and no less important oppressions. Aukin also invokes the memories of “Rosa Luxemburg / Eleanor Marx / Emma Goldmann” (109-11), all radical communist activists, pushing her feminism farther to the economic left than other liberal second-wave feminists of the time.

editorial statement, she writes about “resenting Zionism because / it produces a conflict of loyalties” (51-52) and “remembering / bagels and cheese / are a ball and chain / and my sister in Morocco / has never heard of Kvetches” (124-128). Both of these statements reflect the way Aukin relates Jewish feminism to other social justice movements, such as the desire for peace in the Middle East and “Third World Feminism” expressed by the recognition of the shared oppression of both Western and non-Western women. While noting that the expectation that Western Jewish women are housekeepers is oppressive (“bagels and cheese / are a ball and chain”), Aukin makes sure to dually recognize that her “sisters” in the non-Western world are faced with different and no less important oppressions. Aukin also invokes the memories of “Rosa Luxemburg / Eleanor Marx / Emma Goldmann” (109-11), all radical communist activists, pushing her feminism farther to the economic left than other liberal second-wave feminists of the time.

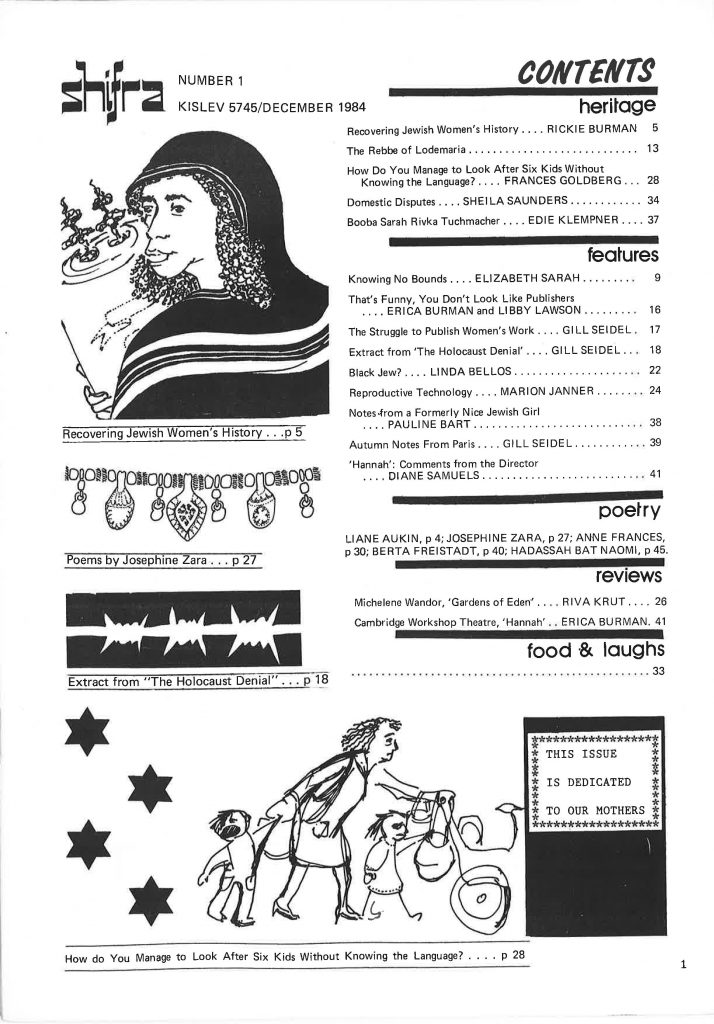

Shifra, published for a short time in England in the mid-eighties, had a smaller circulation and audience than Sinister Wisdom but nonetheless articulated similar radical politics. On the first page, a small graphic is accompanied by text reading “this issue is dedicated to our mothers” (1). The following two pages contain editorial letters, where the collective authors declare that:

“Shifra is part of an ongoing resistance movement. Through articles, sharing personal experiences, history and poetry, we challenge the privileges of men over women, non-Jew over Jew, white over Black, heterosexual over Lesbian…As Jewish women we want to build a strong, effective presence which comes from the experiences of our foremothers, and is firmly part of the Women’s Liberation Movement. The Struggles of Jewish women, past, present and future, live in Shifra (2).”

a strong, effective presence which comes from the experiences of our foremothers, and is firmly part of the Women’s Liberation Movement. The Struggles of Jewish women, past, present and future, live in Shifra (2).”

Shifra, like The Tribe of Dina, places a strong emphasis on intergenerational connection and history. However, Shifra is more explicit in its attempt to “challenge the privileges” that create oppression for all people and not simply Jewish women. To be sure, Shifra represents a number of views and also ran pieces such as “How Do You Manage to Look After Six Kids Without Knowing the Language?” that discusses the difficulties Jewish immigrant mothers experienced while working and raising children and battling questions of assimilation in the capitalist workplace.