A Brief History of Rape Law

The fist rape law emerged in Babylon during c.1900 BC. The Code of Hammurabi dictated that if a man forces sex upon another man’s wife or if a man forces sex upon a virgin woman that “is living in her father’s house,” then “that man should be put to death” (Gold). This set a legal precedent that rape was merely a form of theft and vandalism, since women were considered property. Hence, the idea of a husband “forcing sexual intercourse” upon his wife was deemed the man’s legal right. Ancient society viewed rape as morally depraved, not because it caused the woman harm, but because it harmed male honor. Society viewed raped women as damaged goods and no longer marriageable assets. Speaking toward this idea that rape was merely an issue of one man damaging another man’s property, Winnie Tomm concludes that “by contrast, rape of a single woman without strong ties to a father or husband caused no great concern” (Tomm). This view remained constant for centuries until English law in the 1600’s created the first shift in society’s perception of rape by re-defining the criminal act as “the carnal knowledge of any woman above the age of 10 years against her will” (Gold).

These two laws were combined in the United States. Common law in the US declared that “a person commits rape when he has carnal knowledge of a female, not his wife, forcibly and against her will” (Gold). The law’s structure and general concept mirror English law quite closely; however, the Code of Hammurabi’s shadow belied the underlying morals. The qualification injected into the center of the law, stating that rape is only considered a crime when it is committed outside the bonds of marriage, alludes to the principles in ancient Babylonian law that define women as male property. United States’ past common law can be broken down as follows: “Carnal knowledge“ was further defined in US law in 1954 via Copeland v. State trial, which declared that “it shall not be necessary to prove the actual omission of seed, but the crime shall be deemed complete under proof of penetration only” (Copeland v. State). “Forced and against her will” indicates that the incident is not considered rape unless it meets both of these qualities beyond a reasonable doubt. It must be thoroughly proved that the woman was violently forced (the court often demanded to see physical injury to satisfy this aspect) and that the woman in no way desired sexual intercourse at the time (Kilpatrick).

Because “non-consent” was an integral element of the crime and because the US law

states that a criminal is innocent until proven guilty, the burden fell upon the woman to prove that she offered no indication of consent. Society pre-judged women in rape trials as guilty of promiscuous behavior, so to provide irrefutable proof of victimization was a Herculean feat. At the time, when a woman was raped, she would enter the legal system addressed as a defendant and witness. She was not declared a victim unless at the close of the trial the man was found undeniably guilty of forcing sexual intercourse upon her without any indication whatsoever, of her desire for said intercourse (Kilpatrick).

states that a criminal is innocent until proven guilty, the burden fell upon the woman to prove that she offered no indication of consent. Society pre-judged women in rape trials as guilty of promiscuous behavior, so to provide irrefutable proof of victimization was a Herculean feat. At the time, when a woman was raped, she would enter the legal system addressed as a defendant and witness. She was not declared a victim unless at the close of the trial the man was found undeniably guilty of forcing sexual intercourse upon her without any indication whatsoever, of her desire for said intercourse (Kilpatrick).

Women were forced off the streets and forced into silence. Women knew that if they were the object of a sexual assault, the law would not protect them (Bevacqua). Then, the Second Wave feminist movement began. Women started encouraging each other to speak out and act out against the injustices they faced. Writers like Susan Griffin in 1970 began shocking people out of their complacency about rape calling it a “form of mass terrorism.” Griffin wrote about how rape restricted women’s lives because they lived in terror, in abject fear of going out alone: “[women] will not be free until the threat of rape and the atmosphere of violence is ended, and to end that the nature of male behavior must change” (Griffin). Anti-rape activists worked within the Second Wave feminist movement to address the issue of rape on a variety of levels: consciousness raising, support, and legal changes.

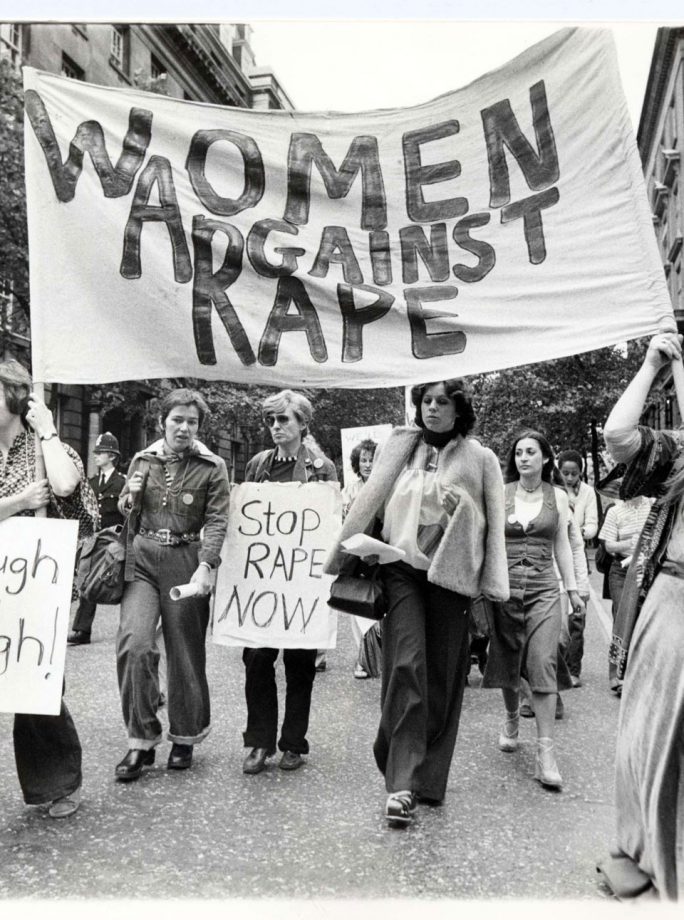

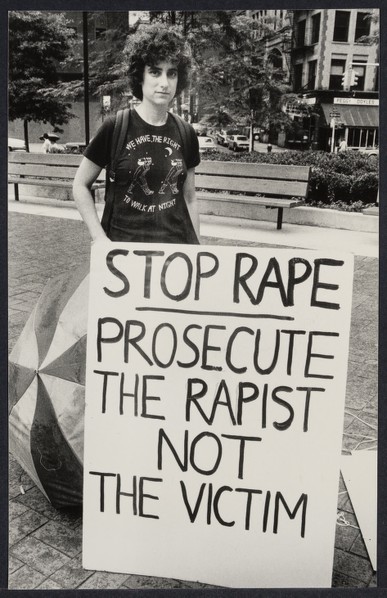

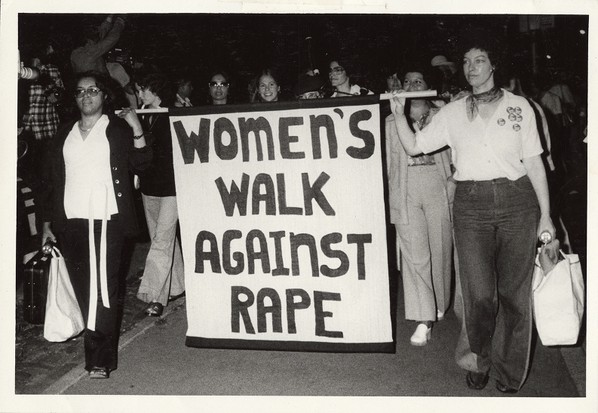

Three of the various ways in which feminists brought awareness to the rape epidemic and the need for change were through consciousness raising groups, large public events, and poetry. In the late 1960’s, women began gathering in small groups and sharing their personal stories about rape incidents and other traumatizing experience. These little gatherings were called consciousness raising groups. On January 24, 1971, The New York Radical Feminist group held their first Speak-Out, a large public gathering where women could share their stories with each other. This event was so successful that The New York Radical Feminist group held a follow-up conference about rape that April (Rose). More events like this emerged throughout the nation. A series of marches began in 1976 called Take Back the Night marches. Numerous women participated in these rallies to protest sexual assault and fight for the right to walk the streets at night without fear (Hibsch). However, events like these and physical get togethers were not the only forms of consciousness raising. A third form was poetry printed in radical publications and read aloud in community poetry readings. Such poetry is the primary focus of the posts to follow.

First Take Back the Night March

Support of rape survivors was another important strategy. Community gatherings, as mentioned above, provided a significant degree of moral and emotional support to rape survivors, but one of the critical breakthroughs that arose from the Second Wave feminist movement was the establishment of rape crisis centers. The Bay Area Women Against Rape (BAWAR) opened the first two rape crisis centers in 1971, located in California and Washington DC (Kilpatrick). According to BAWAR’s website, their founding mission was, and still is, to “establish a place where rape and incest survivors could receive quality counseling and advocacy they need” (BAWAR).

Finally, the most crucial need that anti-rape feminists devoted themselves to resolving was legal change. Spearheaded primarily by the National Rape Task Force, a subsection of the National Organization for Woman, feminists began campaigning relentlessly to redefine rape as a crime of violence (National Organization for Women). And, in 1974, Michigan created the first successful attempt to legally redefine rape. Known as the Criminal Sexual Conduct Law, this bill not only established a broader definition of rape, but it also outlawed spousal rape (Bevacqua). Other states followed Michigan’s example, and finally in 1996, Georgia, the last of the fifty states, outlawed marital rape as well (Degnan). Today, due to changes made in 2012, the FBI defines rape as “the penetration, no matter how slight, of the vagina or anus with any body part or object, or oral penetration by a sex organ of another person without consent of the victim” (Savage).

Even with the incredible changes, catalyzed by activists in the Second Wave feminist movement, the war against rape has still yet to be won.

Sources:

“About.” The Bay Area Women Against Rape , BAWAR, https://www.bawar.org/about/.

Bevacqua, M, Rape on the Public Agenda: Feminism and the Politics of Sexual Assault. Northeastern University Press, 2000.

Bierschbach, Briana. “This Woman Fought To End Minnesota’s ‘Marital Rape’ Exception, And Won.” NPR, NPR, 4 May 2019, https://www.npr.org/2019/05/04/719635969/thiswoman-fought-to-end-minnesotas-marital-rape-exception-and-won.

“Copeland v. State.” Justia Law, https://law.justia.com/cases/florida/supreme-court/1954/76-so2d-137.html.

Effgen, Christopher. United States Crime Rates 1960 – 2018, http://www.disastercenter.com/crime/uscrime.htm.

“Get Statistics.” National Sexual Violence Resource Center, https://www.nsvrc.org/node/4737.

Gold, Sally, and Martha Wyatt. “The Rape System: Old Roles and New Times.” Catholic University Law Review, vol. 2, no. 4, 1978, pp. 695–727, http://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview/vol27/iss4.

Griffin, Susan. “Rape Is a Form of Mass Terrorism.” The American Women’s Movement: a Brief History with Documents, edited by Nancy MacLean, Bedford/St. Martins, 2009, pp. 99-100.

Hibsch, Jimmy. “Students ‘Take Back the Night’ on Columbia Streets.” Maneater,https://www.themaneater.com/stories/campus/students-take-back-night.

“Highlights.” National Organization for Women, https://now.org/about/history/highlights/.

Kilpatrick, Dean G. “ Rape and Sexual Assault .” National Violence Against Women Prevention

Research Center , Medical University of South Carolina https://mainwebv.musc.edu/vawprevention/research

Lockwood, Patricia. “Rape Joke.” The Awl, 25 July 2013.

Maschke, Karen J. The Legal Response to Violence against Women. Garland, 1997.

“Patricia Lockwood on the ‘Rape Joke.’” Facebook Watch, 28 Apr. 2017, https://www.facebook.com/Channel4News/videos/10154790859176939/?v=1015479089176939&external_log_id=644ca1a3ece124581c12b64a3234b9bd&q=Channel 4 News rape joke.

Peiss, Kathy Lee, et al. Passion and Power: Sexuality in History. Temple University Press, 1989.

Rose, V.M, “Rape as a social problem: a byproduct of the feminist movement,” Social Problems,1977.

Sanders, Teela. The Oxford Handbook of Sex Offenses and Sex Offenders. Oxford University Press, 2017.

Savage, Charlie. “Federal Crime Statistics to Expand Rape Definition” The New York Times,14 Apr. 2018. Patricia-lockwood-rape-joke-poem-is-world-famous.

Tomm, Winnie. Bodied Mindfulness: Women’s Spirits, Bodies, and Places. Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1995.

Yllo, Kersti A., and M. Gabriela Torres. Marital Rape: Consent, Marriage, and Social Changein Global Context. Oxford University Press, 2016.