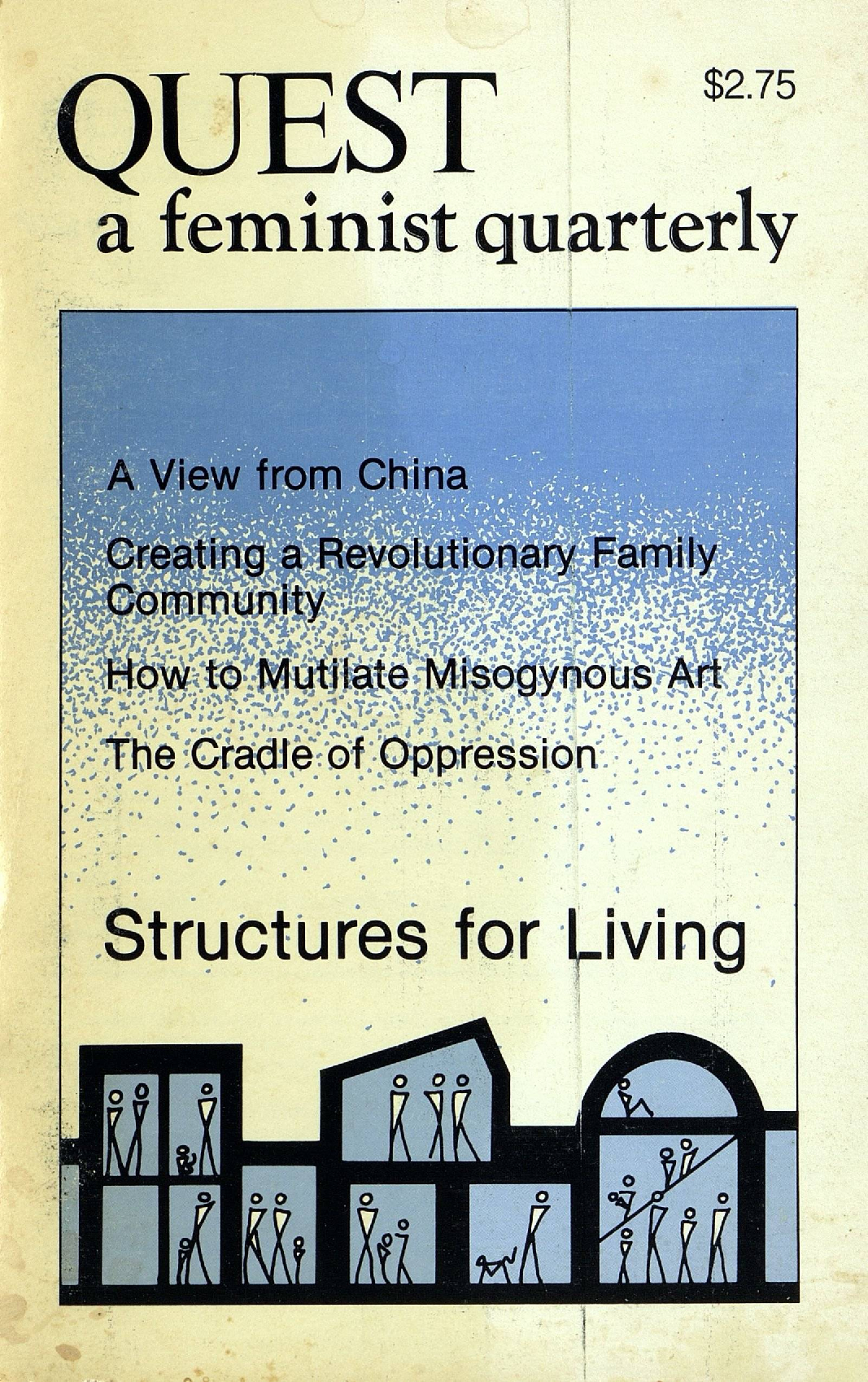

Quest‘s “Structures for Living” issue features a cover with striking similarities to Su Negrin’s artwork on the cover of Women 2.2. A design editor for the magazine, artist Sarah Shepard contributed many pieces in the later volumes of Quest. Her cover here depicts different compositions of families inside closed boxes and shapes. Like Negrin’s cover, the people are confined to the box they are in. However, unlike the tension and pain so evident in the How We Live and With Whom cover, we see family members content in the home. The piece depicts single parents, same sex parents, extended families, and even a single individual home. Notably, one box includes a thin diagonal line across its area. Four individuals are on each side of the line. Presumably, this box represents a communal living situation. As the How We Live and With Whom editorial explains, “communal living can be a liberating experience” that allows us all to “come out better people” (Women 2.2, 1).

Quest‘s “Structures for Living” issue features a cover with striking similarities to Su Negrin’s artwork on the cover of Women 2.2. A design editor for the magazine, artist Sarah Shepard contributed many pieces in the later volumes of Quest. Her cover here depicts different compositions of families inside closed boxes and shapes. Like Negrin’s cover, the people are confined to the box they are in. However, unlike the tension and pain so evident in the How We Live and With Whom cover, we see family members content in the home. The piece depicts single parents, same sex parents, extended families, and even a single individual home. Notably, one box includes a thin diagonal line across its area. Four individuals are on each side of the line. Presumably, this box represents a communal living situation. As the How We Live and With Whom editorial explains, “communal living can be a liberating experience” that allows us all to “come out better people” (Women 2.2, 1).

The first article in this edition of Quest, Ann Ferguson’s “The Che-Lumumba School: Creating a Revolutionary Family Community,” cites that only 15.9 percent of families in the US have a stereotypical nuclear family. “This gap between reality and the idea [of a nuclear family],” Ferguson explains, “creates a crisis in values for most people” (Quest 5.3, 13). Her article discusses the internal inconsistencies within the nuclear family. She challenges “the breakdown of the public-private split which placed men as breadwinners and women as housemakers” (Quest 5.3, 14). Ferguson proposes a new way to define family. Composed of individuals who may live separately but who contribute to a community of “self-conscious resistance,” her proposed revolutionary family community emphasizes the economic, social, psychological, and political equality of its members (Quest 5.3, 15). Ferguson concludes with a final plea for Quest readers to consider this alternative family structure. “Revolutionary family-communities,” she asserts, “[are] structures we will need for the long haul ahead toward a socialist-feminist revolution” (Quest 5.3, 26).

Four women coauthor the article “Mother/Daughter Roles in the Feminist Movement.” Two are mothers and the other two have no children. These women “believe that the imposition of  mother-daughter stereotypes is an important tool for the oppression of women: the roles either exclude us from power, or attach demeaning traits to the power we have been allowed” (Quest 5.3, 71). As many women are both daughters and mothers, the authors explain that “whether we are put into the mother role or the daughter one can depend on such factors as appearance, age or power differences” (Quest 5.3, 74). The authors continue, “Traditionally, the only way for women to have even a semblance of power is as mothers” (Quest 5.3, 75). In acknowledging this unfortunate truth, these women make clear that women who do not fit nicely into the structure of the nuclear family face even greater oppression than women who do. Those who cannot or choose not to have children have a greater power discrepancy between themselves and men. The hierarchy among female power, especially that within the family, can be mended, as these female writers suggest, with co-nurturing. “We define co-nurturing,” the authors explain, “as nurturing and caring between equals; unlike mothering, it carries the expectation that the nurturing will be reciprocal and neither will have control over the other” (Quest 5.3, 78). This idea parallels with several other ways of mending the nuclear family discussed in feminist periodicals. Woman‘s “How We Live and With Whom” issue, for example, proposes a way to combat the challenge of oppressive norms that manifest as a result of the nuclear family: “If we want our children to be critical of the status quo, we must raise them to question our authority over them” (Women 2.2, 1).

mother-daughter stereotypes is an important tool for the oppression of women: the roles either exclude us from power, or attach demeaning traits to the power we have been allowed” (Quest 5.3, 71). As many women are both daughters and mothers, the authors explain that “whether we are put into the mother role or the daughter one can depend on such factors as appearance, age or power differences” (Quest 5.3, 74). The authors continue, “Traditionally, the only way for women to have even a semblance of power is as mothers” (Quest 5.3, 75). In acknowledging this unfortunate truth, these women make clear that women who do not fit nicely into the structure of the nuclear family face even greater oppression than women who do. Those who cannot or choose not to have children have a greater power discrepancy between themselves and men. The hierarchy among female power, especially that within the family, can be mended, as these female writers suggest, with co-nurturing. “We define co-nurturing,” the authors explain, “as nurturing and caring between equals; unlike mothering, it carries the expectation that the nurturing will be reciprocal and neither will have control over the other” (Quest 5.3, 78). This idea parallels with several other ways of mending the nuclear family discussed in feminist periodicals. Woman‘s “How We Live and With Whom” issue, for example, proposes a way to combat the challenge of oppressive norms that manifest as a result of the nuclear family: “If we want our children to be critical of the status quo, we must raise them to question our authority over them” (Women 2.2, 1).