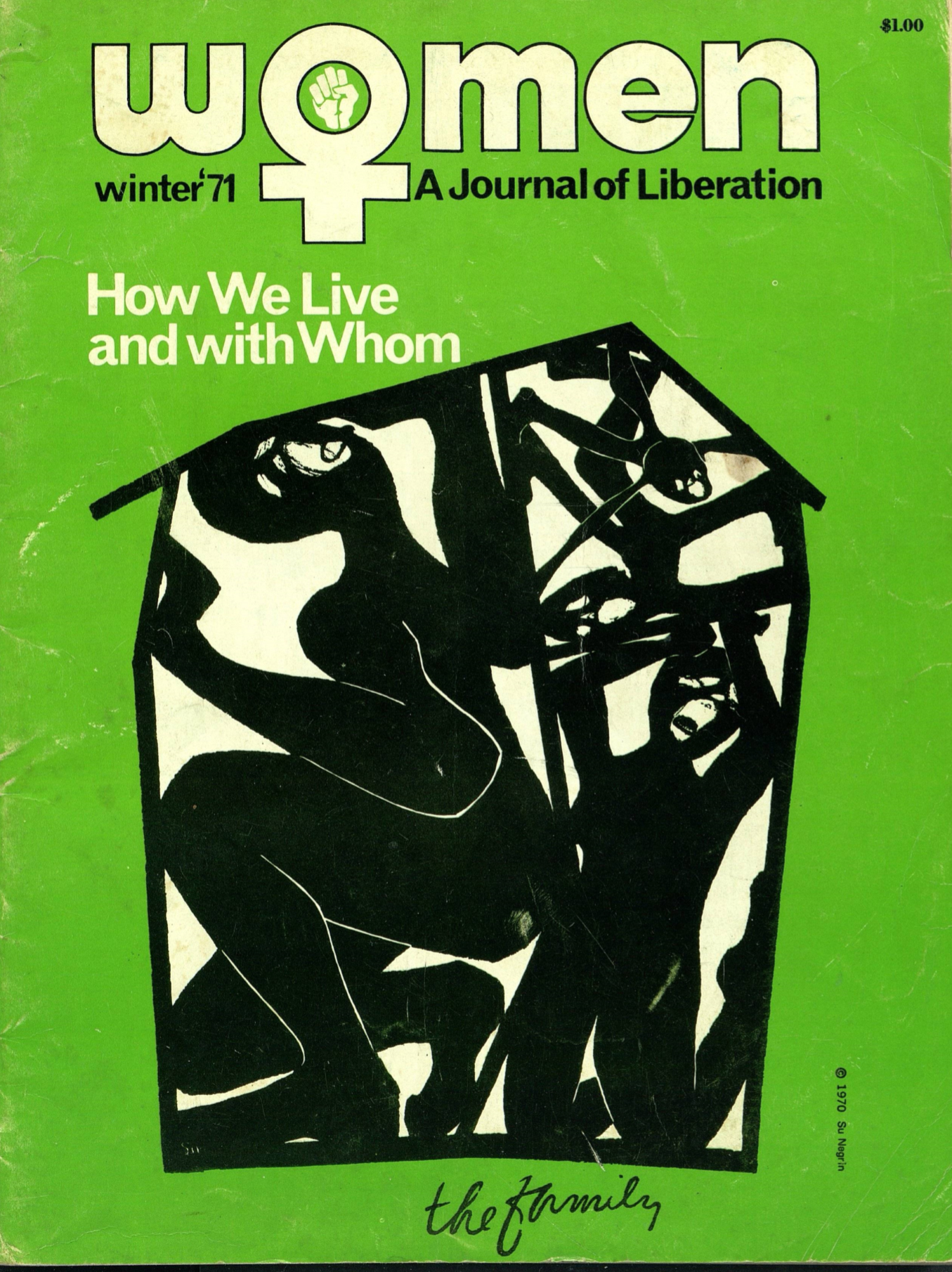

Published in the winter of 1971, the second issue of the second volume of Women: A Journal of Liberation focuses on “How We Live and with Whom.” The journal’s components explore women’s relationships with all members of the family – husband, children, parents, siblings. In addition to explaining these interfamilial relationships, the journal spotlights the ways women have explored, challenged, and transgressed the norms of how we live and with whom.

The magazine’s editorial features two sections: The Nuclear Family and Communal Living. The sixteen-member, all-female staff uses the piece to detail the restrictions of the nuclear family, which include the often “possessive [parental] relationship filled with jealousy and anger because of the impossibility of two people filling all each other’s needs” (Women 2.2, 1). Relationships within the family center around “feelings of hostility and competition” (Women 2.2, 1). Children perpetuate the cycle of oppression manifested in the nuclear family because this often harmful and problematic relationship between their mother and father is their “first and most enduring experience with power relationships” (Women 2.2, 1). Still, the staff acknowledges that the majority of its members operate within a nuclear family and that there exist real anxieties about transgressing this structure. Communal living, one alternative to the nuclear family, provides opportunities for productivity, inclusivity, and liberation, the editorial explains. But in addition to the implications of simply defying a so deeply engrained societal norm, fears of losing personal independence, increased sexual tensions, and neglect of the children’s needs are some of the barriers that prevent women from moving away from the nuclear family despite its framework of an “unhappy way for people to live” (Women 2.2, 1). Much of the journal focuses on the means by which we can question and overcome the “authoritarian system” and cycles of oppressive norms that exist in our culture as a result of this family structure (Women 2.2, 1). The editorial proposes one way to combat this challenge: “If we want our children to be critical of the status quo, we must raise them to question our authority over them” (Women 2.2, 1).

The magazine’s cover enhances the theme of the restraints of and tensions within the nuclear family. The cover features a graphic design entitled “The Family” by Su Negrin, author of A Graphic Notebook on Feminism. Against a neon green background, the cover’s artwork is black and white. It features four individuals – two children, a mother, and father – trapped inside of the outline of a house. While the people’s shapes initially catch the viewer’s attention, closer inspection reveals a more hidden detail: the mother, father, and two children are separated by walls between them. This separation serves as a visual representation of the “great loneliness” each member of the family feels (1). Each of the four bodies contort to fit into their small and isolated section of the home. Facial expressions of pain – wide eyes and screaming mouths – depict the “[unhappiness]” the staff describes in the editorial (Women 2.2, 1). The two children, together in one box in the upper right, occupy the least amount of square footage of the house. One child’s face boarders the parents’ boxes. The other child’s face is in the center of the box. The father’s body consumes just less than a third of the house’s space in the bottom right. His head and arms reach up towards his children. The mother inhabits the rest of the house, over half of the total space. Her curvy body crouches to fit into the box that is too small to contain her. The image seems to represent the traditional roles of the husband as the family’s “breadwinner” and the wife as the doer of housework and caregiver to the children (Women 2.2, 1). All four people’s arms and legs press against the boxes they occupy as they strive to escape the confines of the nuclear family. In contrast to the children and husband, though, the wife’s head also presses firmly against the outside of the house – the roof, in particular. Likely unsatisfied by her husband – who “finds ego consolation in dominating [her]” – and children with whom she shares a competitive relationship, the woman reaches for the outside almost as if she is gasping for air; not only does she want to break free of the nuclear family, but she needs it to thrive. While tension fills the house, the remainder of the journal’s cover is empty of illustrations. Despite the structure seemingly ready to burst at the seams, the outside world operates normally, blind by choice to the loneliness and misery within the restrictive household.