Muscogee (Creek) Nation poet Joy Harjo is a renowned “fire-tender.” She was named the twenty-third Poet Laureate of the United States in 2019 and is widely recognized for her ability to express the Native experience, female expression and liberation, and the power of the earth in her poetry (Zongker). Her poem “From the Salt Lake City Airport-82,” originally published in A Gathering of Wisdom, integrates decolonization and womanhood, two essential themes of Indigenous feminism.

Throughout the poem, Harjo invokes the being-ness of the natural world and ties the history of the land to the history of Indigenous people: “The Wasatch Mountains plead / to be remembered. / in the East. / They watched wagon trails / wear down men, allowed them / to cross their bellies / thinking these white skins / could learn to love this land / as much as them, and the darker ones / already here” (145). Harjo speaks to how the earth itself has witnessed the simultaneous destruction of it’s own body and those of Native Americans carried out by white settlers.

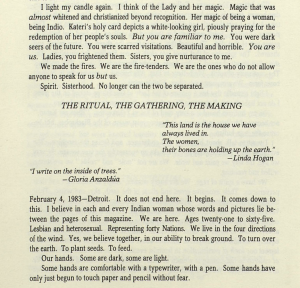

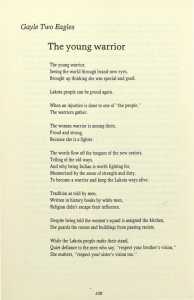

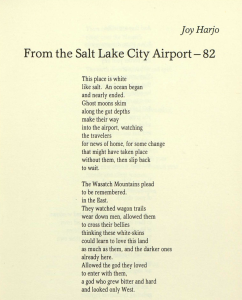

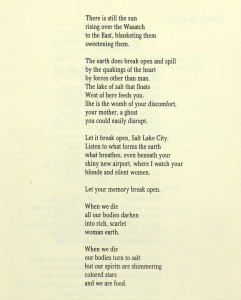

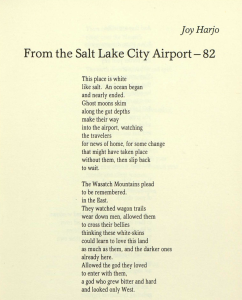

The first two stanzas of Joy Harjo’s poem “From the Salt Lake City Airport — 82.”

White colonialism extracts life from the earth and also seeks to erase Native culture in its mission to develop and civilize. As a result, Harjo points out that white, patriarchal society is divorced from the land and life itself: “They build a city of separation. / Grew children / and named them names of men, / another language / not the land” (145). The inherent culture in white society is not of the land or the feminine, but of the male and inanimate that perpetuates the dominant language of capitalism and exploitation. The histories of the earth and Indigenous peoples are thereby interlaced: “It is a crazy, dangerous joke / to forget the red hills / that border your city / with passion. / They are mirrors / that make you hate yourself / for what you didn’t / want to remember” (146). Here, Harjo directly references the ignorance of the history of genocide and oppression against Indigenous peoples that society was founded upon. The land embodies those histories and serves as a reminder to combat the continued oppression of the land and Indigenous peoples, especially to those of us who benefit from that exploitation and robbery.

While the land is intrinsically tied to Indigenous culture, there is an even deeper connection between the earthen and the feminine and their shared history of violation: “Salt Lake City, / you grow hot and ashamed / when you look East, / and feel uncomfortable / with the power of the womb, / and place the blame / on the devil / and your wives” (146). White culture is patriarchal and ignores the inherent “power of the womb,” subjecting women to inferior roles in society rather than the forces of change and power that they embody. Here, Harjo echoes rhetoric from the Second Wave of Feminism by challenging the Manifest Destiny ideology that elevates the patriarchy, but she also importantly calls upon white women for their complicity in oppressing people of color: “I see your women caught behind windows / in their homes, behind rows and rows / of bleached and frightened children. / They speak men’s words, not their own / except those languages they’ve learned to speak in secret / and in dreams, if they’ve / not forgotten” (146).

In these last two lines, Harjo makes a turn in the poem by suggesting the possibility that some women have not forgotten the vital language of truth, the earth, and the life force of womanhood. Harjo understands that language, in addition to being a tool of liberation, has historically been used as a weapon to suppress thought and dialogue. Harjo is among many Native poets who speak the language of resistance, who are fluent in these dialects of freedom, reciprocity, spirituality, and intergenerational connection. White women in the Second Wave of Feminism were only beginning to find their own words, and are still learning the difference between appropriating the experiences of women of color and authentically making space for Indigenous feminist voices within the movement.

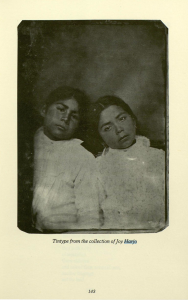

Portrait of Joy Harjo taken by LaVerne Harrell Clark in Albuquerque, NM, 1975.

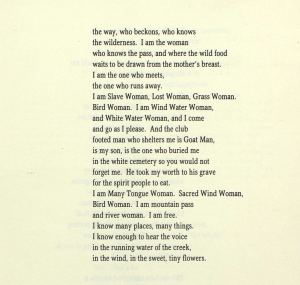

Harjo continues to look towards the future: “I see tribes / gathering themselves together / not for war, but for recognition” (146). By envisioning this acknowledgement in spaces of gathering that prioritize neither war nor reconciliation but recognition of history and responsibility, Harjo actively challenges the status quo of silence and ignorance that has perpetuated systems of oppression. Action against these systems necessitates the empowerment of femininity and indigeneity: “The Earth does break open and spill / by the quakings of the heart / by forces other than man. / The lake of salt that floats / West of here feeds you. / She is the womb of your discomfort, / your mother, a ghost / you could easily disrupt” (147). Harjo returns to the theme of white mens’ fear of the earth and thus their drive to conquer it, a fear related to their fear of the deep, natural force of women that threatens to dismantle mens’ hierarchies of power.

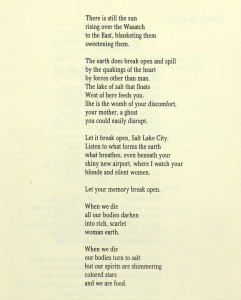

The final stanzas of Harjo’s poem.

Harjo once again emphasizes that the power of women’s liberation is bound to the liberation of truth. As she urges her reader to “Let your memory break open,” Harjo asks us to remember the history of this land and let it move us to change (147). The land, after all, is our greatest teacher. Harjo exemplifies Indigenous feminism in the final lines of her poem: “When we die / all our bodies darken / into rich, scarlet / woman earth. / When we die / our bodies turn to salt / but our spirits are shimmering / colored stars / and we are food” (147). Harjo is no stranger to the relation between the generative force of women as makers of change and the soil of the earth where natural processes of renewal take place. Women are sources of regeneration, the eternal tenders of the flame of revival. Harjo leaves us with the knowledge that the way forward must be to decolonize, indigenize, and womanize our systems of life so that future generations may grow stronger from a more fertile ground.

Sources:

Brant, Beth. Sinister Wisdom: A Gathering of Spirit, no. 22/23, Iowa City Women’s Press, 1983.

Clark, LaVerne Harrell. Joy Harjo, Albuquerque, 1975, Silver Birch Press, https://silverbirchpress.wordpress.com/2013/08/17/eagle-poem-by-joy-harjo/.

Harjo, Joy. “From the Salt Lake City Airport-82,” Sinister Wisdom: A Gathering of Spirit, no. 22/23, pp. 145-147.

“Joy Harjo.” Joy Harjo Website, 2021, https://www.joyharjo.com/.

Zongker, Brett. “Joy Harjo Appointed to Third Term as U.S. Poet Laureate,” Library of Congress,10 November 2020, https://www.loc.gov/item/prn-20-075/joy-harjo-appointed-to-third-term-as-u-s-poet-laureate/2020-11-19/.