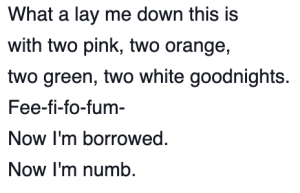

The final stanza of “The Addict,” a poem by Anne Sexton published in the collection Live or Die in 1966. The poem is about a woman who becomes addicted to tranquilizers and cannot recover.

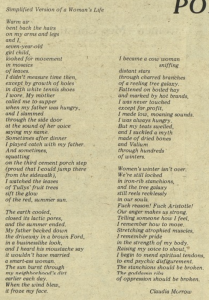

In “The Addict,” a lyric poem by Anne Sexton, an icon of Second-Wave Feminism, a woman becomes addicted to tranquilizers and slips into unconsciousness. At the beginning of the poem, published in the collection Live or Die (1966), the narrator is already addicted, as she takes “eight [pills] at a time from sweet pharmaceutical bottles” (Sexton line 4). The narrator denies her addiction, claiming that she’s “merely staying in shape,” which mirrors the false abilities of such drugs that physicians promoted, yet she admits that she’s “becoming somewhat of a chemical mixture” (14, 23-24). This indecisiveness is present throughout the stanzas of the poem: the narrator is so subdued by the drugs she’s addicted to that she cannot discern whether or not she is addicted to the drugs. In the fourth stanza, the vivid metaphor, “It’s a kind of war / where I plant bombs inside / of myself” indicates that the narrator knows that she is endangering herself, yet in the sixth stanza, she compares her pills to the much more favorable “eight chemical kisses” (32-34, 54). However, these kisses are not kisses of love but of death, which is communicated by the final three lines, “Fee-fi-fo-fum – / Now I’m borrowed. Now I’m numb:” the pills have won (58-60). Sexton concludes on this note of loss of bodily autonomy and control to explicitly warn her female audience of the threat tranquilizers pose to their bodies and their capacity for self-awareness.

Work Cited:

Sexton, Anne. “The Addict.” Live or Die: Poems, e-book ed., New York City, Open Road Integrated Media, 2016, pp. 91-92.