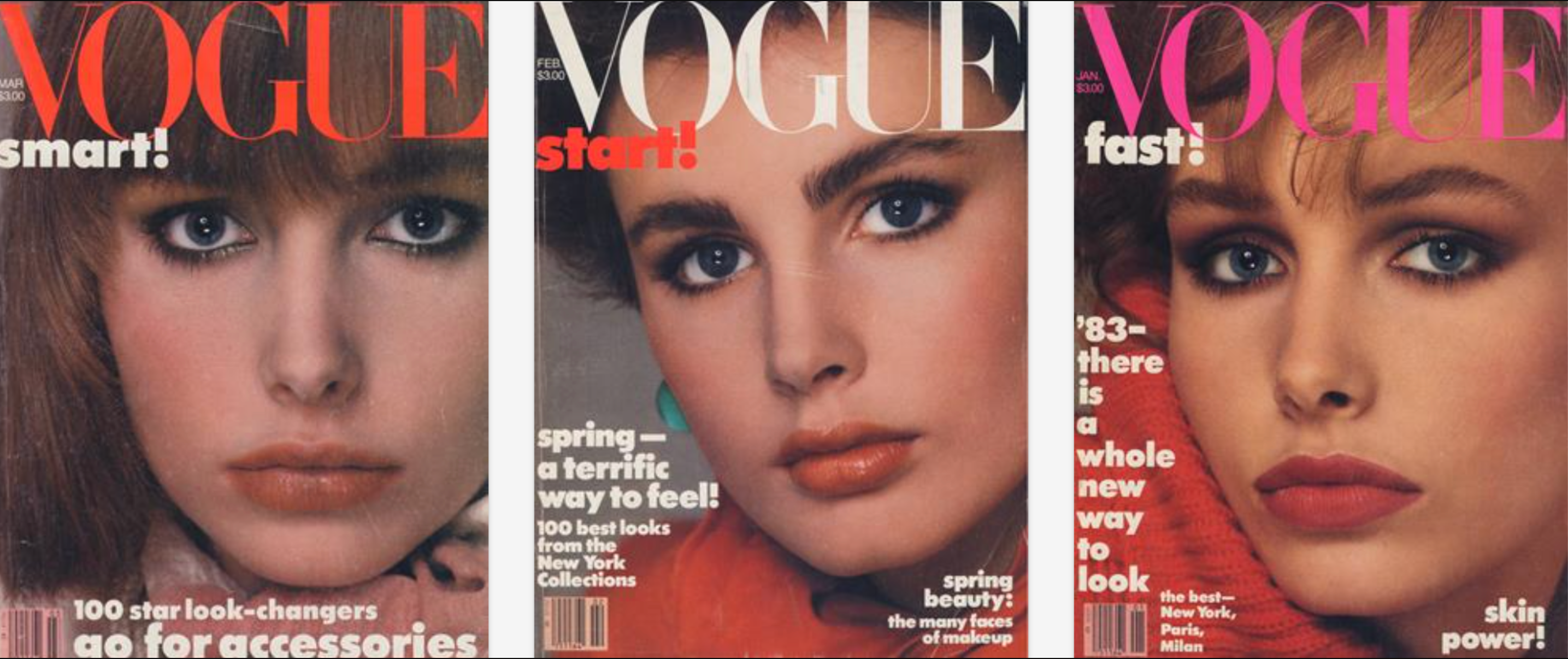

Covers of Vogue from January through March of 1983, respectively. Depicted are three white women with Eurocentric features and expressionless faces. The mainstream journal caters to younger women who are interested in trends in fashion and beauty, however it exclusively featured white models during the 1980s.

Vogue was among the most popular journals in mainstream media during the Second Wave of the feminist movement, making it highly influential to the women who read it. The covers of three consecutive issues of Vogue from January through March of 1983 consist of white women with doll-like features such as blue eyes, upturned noses, a defined bone structure, and straight hair. Additionally, the women are expressionless, emphasizing that blank eyes and pursed lips need to mask their authentic personalities because women’s beauty should be their sole defining factor. The lack of smiles shows that a woman’s happiness is never made a priority, and further proves how the objectification of women serves to please men, not women.

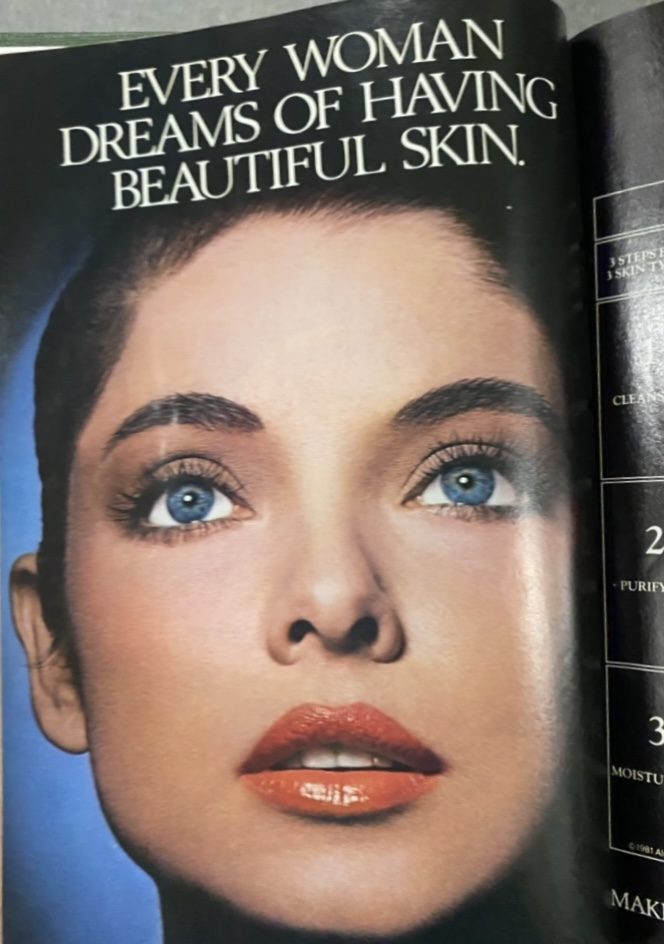

“Every Woman Dreams of Having Beautiful Skin” advertisement in Vogue, January 1983. The woman in the photo is also expressionless and white with Eurocentric features, further objectifying women throughout the issue.

The beauty standard in the form of a single type of woman is not only seen on the cover pages, but is reinforced throughout each issue. The page from the January 1983 issue presents a woman of the same type, and accompanying it is a caption that reads “all women dream of having beautiful skin.” What makes the line especially jarring is the claim about all women, as if not dreaming of having beautiful skin makes a woman inherently flawed. It is explicitly projecting the wrong priorities onto its readers by claiming that women should exert all of their energy on improving their physique to meet this standard of beauty. By isolating women who have other ways of valuing themselves, these magazines make them feel alone. The advertising companies take advantage of this vulnerability, and they work by setting unrealistic expectations for women that make them feel like they need to invest in the advertised products in order to be on par with other women.

Works Cited

“Vogue,” Condé Nast. Jan. 1983, pp. cover, 22.

“Vogue,” Condé Nast. Feb. 1983, p. cover.

“Vogue,” Condé Nast. Mar. 1983, p.cover.