As feminism gained ground within academic communities and institutions, a number of scholars sought to expand Judaic studies’ curriculum to include women’s and gender studies. Scholars aimed to frame women in Jewish scholarship within the already-existing academy, adhering to the liberal (or non-radical) practices of second wave feminism. “The  Jewish Women’s Studies Guide,” compiled by Ellen Sue Levi Elwell and Edward R. Levenson, laid out curricular models to incorporate women into historical, spiritual, and cultural Judaic studies. The guide especially considered new models of learning that strove to reconcile progressive, justice-oriented Judaism and equity between men and women within the religion. In other words, the guide went beyond the simple inclusion of female figures and elevated them to an important status on par with traditional male characters. The guide outlined courses, such as “Women in the Hebrew Bible,” that attempted to promote the already existing female characters in the Hebrew Bible, and also courses such as “Feminist Theories of Religion: The Implications for Judaism” that navigated the existential place of women in a faith constructed by and for men. The compilers of this volume state their inspiration for their work in the introduction:

Jewish Women’s Studies Guide,” compiled by Ellen Sue Levi Elwell and Edward R. Levenson, laid out curricular models to incorporate women into historical, spiritual, and cultural Judaic studies. The guide especially considered new models of learning that strove to reconcile progressive, justice-oriented Judaism and equity between men and women within the religion. In other words, the guide went beyond the simple inclusion of female figures and elevated them to an important status on par with traditional male characters. The guide outlined courses, such as “Women in the Hebrew Bible,” that attempted to promote the already existing female characters in the Hebrew Bible, and also courses such as “Feminist Theories of Religion: The Implications for Judaism” that navigated the existential place of women in a faith constructed by and for men. The compilers of this volume state their inspiration for their work in the introduction:

Feminism, both religious and secular, played a fundamental role in this new thinking…. In 1973, the National Conference on Jewish Women held in New York City attracted 300 Jews. That conference was a major catalyst for the creation of Lilith magazine and the short-lived Jewish Feminist Organization, and it inspired a special issue of Response magazine on Jewish women. (1).

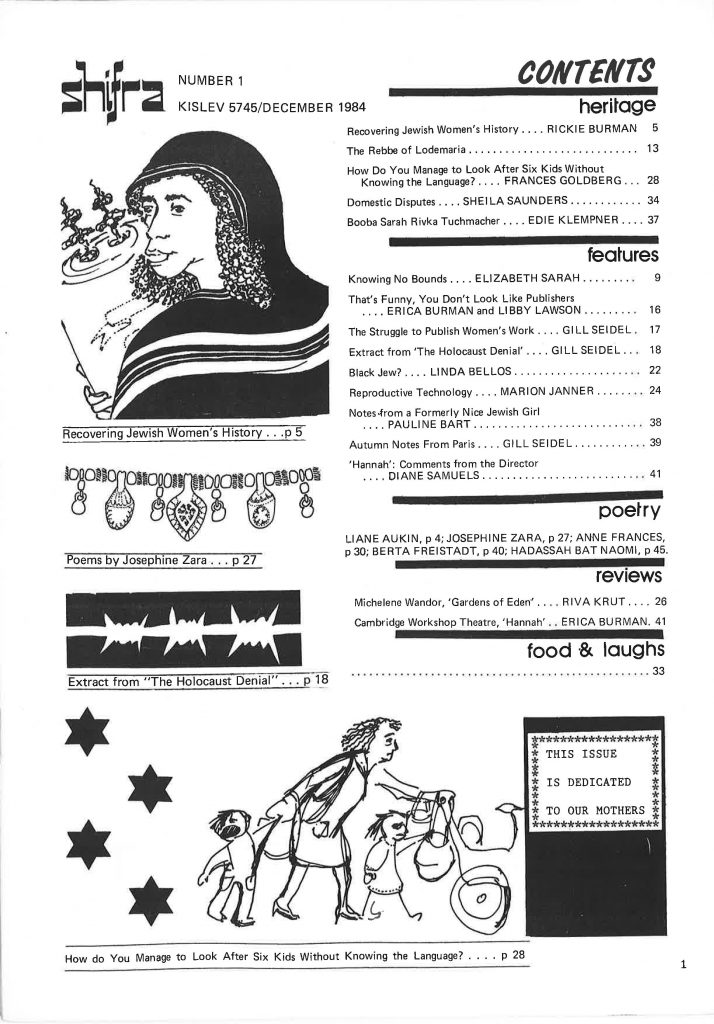

Specifically citing the “special issue of Response” (later anthologized as The Jewish Woman: New Perspectives) and Lilith, this introduction summarizes the extent to which these publications were connected to and inspired by each other. Physical actions and “consciousness raising” catalyzed whole publications, which in turn made space for the creation of new academic curricula. This cycle demonstrates the effectiveness of Jewish women’s organizing and their commitment to creating tangible change in women’s intellectual, personal, and spiritual lives. Notably, both publications referenced here, Lilith and The Jewish Woman, are mainstream and certainly non-radical. Other Jewish feminist literature, such as the periodicals Sinister Wisdom and Shifra, explicitly defined their own content as radical, lesbian-feminist, and separatist.

The Jewish Woman is a lesser-known publication that was written “in the interests not only of Jewish women, but of the vitality of Judaism itself” (xx). This particular emphasis illuminates an important paradigm shift in Jewish feminism. Published in 1973 as a special issue of Response magazine, and anthologized in 1976, “The Jewish Woman” is a classic example of liberal feminism working within the systemic Judeo-Christian religion. Its editors were chosen because of their involvement with the North American Jewish Students’ Network, firmly placing the roots of Jewish feminism in the American higher education system. The book is a “spiritual quest” (1) that, while its credited authors are Jewish women, nearly all the individual writers site Talmud commentary, and the poetry in the volume is by Dylan Thomas and T.S. Eliot. Compared to other intersectional politics of the Second Wave, the feminism articulated in “The Jewish Woman” is white and even male at times. The question then remained for Jewish feminists: how can we do better?

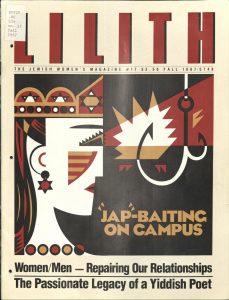

Lilith, founded in 1976 and still publishing, is a Jewish feminist periodical with an estimated peak readership of 25,000 subscribers (Lerner). Aided by its funding and New York City publishing locale, Lilith is one of the most successful second wave publications and likely the most influential among Jewish feminists. Historian Anne Lapidus Lerner notes that “it is the activities fostered by Lilith beyond the covers of the magazine that are most distinctive. Its editor-in-chief is, for example, regularly invited to speak at the General Assembly of the Council of United Jewish Communities” and other wide-reaching public events. The magazine, in over fifty-three years of continuous publication, has covered a wide range of topics but continues to be dedicated to “foster discussion of Jewish women’s issues and put them on the agenda of the Jewish community, with a view to giving women – who are more than 50% of the world’s Jews – greater choices in Jewish life” (vol. 1, no. 1, p. 1).

Founder of Lilith magazine Susan Schneider.

Its articles stay up to date with global affairs, Jewish and non-Jewish, and it continuously integrates poetry and graphic arts throughout, and even features the occasional fiction narrative. The back of each issue ends with a section titled “Tsena Rena” (go out, see) that is subtitled “where to go for what if you’re Jewish and female.” Lilith is dedicated to providing resources for Jewish women to articulate feminism in their religious and secular lives. And while the founding of Lilith marked a certain departure from both “The Jewish Woman” and “The Jewish Women’s Studies Guide,” another decade would pass before Jewish feminists became impassioned about reforming not only their religion, but themselves.

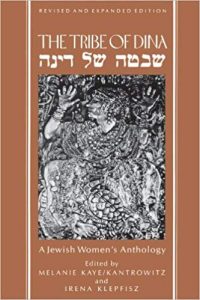

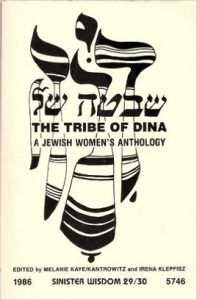

Dina is a Biblical character, the only daughter of Jewish forefather Jacob and his wife Leah, whose brothers founded the twelve tribes of Israel. Dina is only referenced as an accessory to her powerful male relatives, except for a short anecdote about how she left Israel to seek other women. “The Tribe of Dina” is presumably the women Dina sought out in response to her controlling brothers. In using this title, editors of the periodical Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz and Irena Klepfisz reclaim the potential of the tribe of women that never materialized. As the purpose of Sinister Wisdom is to foster a specific lesbian-feminism that includes all women across any number of diversities, “Dina” (as this issue came to be known) is a microcosm of this principle. The editors used this special issue to create a community of Jewish feminists that bridges generations, classes, races, ethnicities, sexual orientations and cultural contexts.

Dina is a Biblical character, the only daughter of Jewish forefather Jacob and his wife Leah, whose brothers founded the twelve tribes of Israel. Dina is only referenced as an accessory to her powerful male relatives, except for a short anecdote about how she left Israel to seek other women. “The Tribe of Dina” is presumably the women Dina sought out in response to her controlling brothers. In using this title, editors of the periodical Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz and Irena Klepfisz reclaim the potential of the tribe of women that never materialized. As the purpose of Sinister Wisdom is to foster a specific lesbian-feminism that includes all women across any number of diversities, “Dina” (as this issue came to be known) is a microcosm of this principle. The editors used this special issue to create a community of Jewish feminists that bridges generations, classes, races, ethnicities, sexual orientations and cultural contexts. In their editor’s notes, Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz and Irena Klepfisz write that “Dina” has a dual purpose: first, to create “coalitions among Jews…..and to connect Sephardic and Ashkenazi Jews, observant and secular, gay and heterosexual, on issues of concern to some or all of us” (345), and second, to fight antisemitism as it intersects with sexism, racism, xenophobia, and classism to oppress Jewish women and all women. Kaye/Kantrowitz and Klepfisz partition the periodical by themes common in Jewish liturgy and communities. The sections each contain poetry, fiction writing, scholarship, and records of family histories: “My Ancestors Speak,” “The Women of Our Family,” “I am the Present Generation,” “Lot’s Wife Revisited,” “Kol Haisha: Israeli Women Speak,” and “Bread and Roses.” The back of the issue contains a glossary of Yiddish and Hebrew words and the graphic credits. Unlike other issues of Sinister Wisdom, “Dina” contains text in three languages (Yiddish, Hebrew, and English), as well as what appear to be family photographs. For example, an ornate border decorates the title page of the chapter “The Women of Our Family” and encloses a grouping of photographs of the writers featured in the chapter. They are of different ages, generations, ethnicities, and religious traditions. This grouping of portraits support “Dina’s” overarching theme of generational connection between Jewish women that is used as a model for creating other types of connection in the literature. As traditional Jewish cultures emphasize the bonds between generations of Jews, “Dina” strives to forge connections between Jewish women beyond those of similar lineage.

In their editor’s notes, Melanie Kaye/Kantrowitz and Irena Klepfisz write that “Dina” has a dual purpose: first, to create “coalitions among Jews…..and to connect Sephardic and Ashkenazi Jews, observant and secular, gay and heterosexual, on issues of concern to some or all of us” (345), and second, to fight antisemitism as it intersects with sexism, racism, xenophobia, and classism to oppress Jewish women and all women. Kaye/Kantrowitz and Klepfisz partition the periodical by themes common in Jewish liturgy and communities. The sections each contain poetry, fiction writing, scholarship, and records of family histories: “My Ancestors Speak,” “The Women of Our Family,” “I am the Present Generation,” “Lot’s Wife Revisited,” “Kol Haisha: Israeli Women Speak,” and “Bread and Roses.” The back of the issue contains a glossary of Yiddish and Hebrew words and the graphic credits. Unlike other issues of Sinister Wisdom, “Dina” contains text in three languages (Yiddish, Hebrew, and English), as well as what appear to be family photographs. For example, an ornate border decorates the title page of the chapter “The Women of Our Family” and encloses a grouping of photographs of the writers featured in the chapter. They are of different ages, generations, ethnicities, and religious traditions. This grouping of portraits support “Dina’s” overarching theme of generational connection between Jewish women that is used as a model for creating other types of connection in the literature. As traditional Jewish cultures emphasize the bonds between generations of Jews, “Dina” strives to forge connections between Jewish women beyond those of similar lineage.

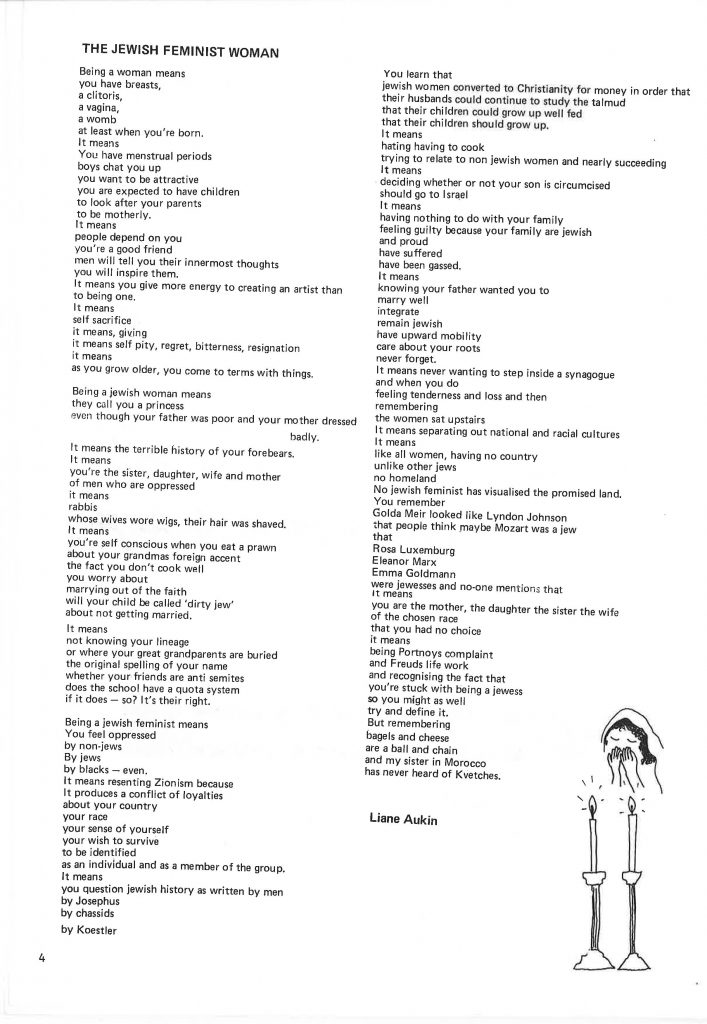

editorial statement, she writes about “resenting Zionism because / it produces a conflict of loyalties” (51-52) and “remembering / bagels and cheese / are a ball and chain / and my sister in Morocco / has never heard of Kvetches” (124-128). Both of these statements reflect the way Aukin relates Jewish feminism to other social justice movements, such as the desire for peace in the Middle East and “Third World Feminism” expressed by the recognition of the shared oppression of both Western and non-Western women. While noting that the expectation that Western Jewish women are housekeepers is oppressive (“bagels and cheese / are a ball and chain”), Aukin makes sure to dually recognize that her “sisters” in the non-Western world are faced with different and no less important oppressions. Aukin also invokes the memories of “Rosa Luxemburg / Eleanor Marx / Emma Goldmann” (109-11), all radical communist activists, pushing her feminism farther to the economic left than other liberal second-wave feminists of the time.

editorial statement, she writes about “resenting Zionism because / it produces a conflict of loyalties” (51-52) and “remembering / bagels and cheese / are a ball and chain / and my sister in Morocco / has never heard of Kvetches” (124-128). Both of these statements reflect the way Aukin relates Jewish feminism to other social justice movements, such as the desire for peace in the Middle East and “Third World Feminism” expressed by the recognition of the shared oppression of both Western and non-Western women. While noting that the expectation that Western Jewish women are housekeepers is oppressive (“bagels and cheese / are a ball and chain”), Aukin makes sure to dually recognize that her “sisters” in the non-Western world are faced with different and no less important oppressions. Aukin also invokes the memories of “Rosa Luxemburg / Eleanor Marx / Emma Goldmann” (109-11), all radical communist activists, pushing her feminism farther to the economic left than other liberal second-wave feminists of the time. a strong, effective presence which comes from the experiences of our foremothers, and is firmly part of the Women’s Liberation Movement. The Struggles of Jewish women, past, present and future, live in Shifra (2).”

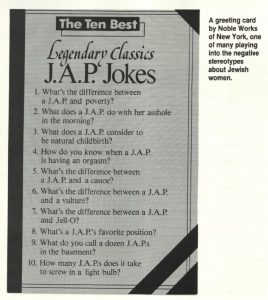

a strong, effective presence which comes from the experiences of our foremothers, and is firmly part of the Women’s Liberation Movement. The Struggles of Jewish women, past, present and future, live in Shifra (2).” The ethnic insult rests on the stereotype that all American Jewish women are materialistic, wealthy, socially inept, and sexually available. In a series of non-fiction articles, Lilith addresses the direct relationship between sexism, anti-Semitism, white supremacy, and violence in an effort to demonstrate to its readers that “JAP jokes” are not jokes at all, but an expression of age-old prejudice that endangers those targeted by such “humor.” The articles pay specific attention to Syracuse University, which the magazine notes as having a large and growing Jewish population and a growing anti-Semitic backlash problem. In his research of the anti-Semitic graffiti that popped up all over campus, sociology professor Dr. Gary Spencer documented and categorized the graffiti in the library carrels and told Lilith that the experience left him “literally shaken” and “nauseated” (9). Dr. Spencer noted that the graffiti ranged from sexist (“all JAPs are sluts”) to annihilationist (“give Hitler another chance” or “this is a warning to

The ethnic insult rests on the stereotype that all American Jewish women are materialistic, wealthy, socially inept, and sexually available. In a series of non-fiction articles, Lilith addresses the direct relationship between sexism, anti-Semitism, white supremacy, and violence in an effort to demonstrate to its readers that “JAP jokes” are not jokes at all, but an expression of age-old prejudice that endangers those targeted by such “humor.” The articles pay specific attention to Syracuse University, which the magazine notes as having a large and growing Jewish population and a growing anti-Semitic backlash problem. In his research of the anti-Semitic graffiti that popped up all over campus, sociology professor Dr. Gary Spencer documented and categorized the graffiti in the library carrels and told Lilith that the experience left him “literally shaken” and “nauseated” (9). Dr. Spencer noted that the graffiti ranged from sexist (“all JAPs are sluts”) to annihilationist (“give Hitler another chance” or “this is a warning to  American JEWS. We will kill you all”) to stand-alone slurs (“kikes”). The professor concluded that “these days, the anti-JAP graffiti have been replaced with vile anti-Semitic slogans….people no longer feel the need to hide an anti-Semitic comment behind a JAP joke” (7). Lilith here attends to an important issue that likely would have resonated with a lot of its audience: female college-age and educated Jewish feminists. By demonstrating the connection between sexism, anti-Semitism, and white supremacy, Lilith reinforces the importance of intersectional solidarity in Jewish feminism, while reminding readers that the fight for Jewish women’s safety and equality was not over yet.

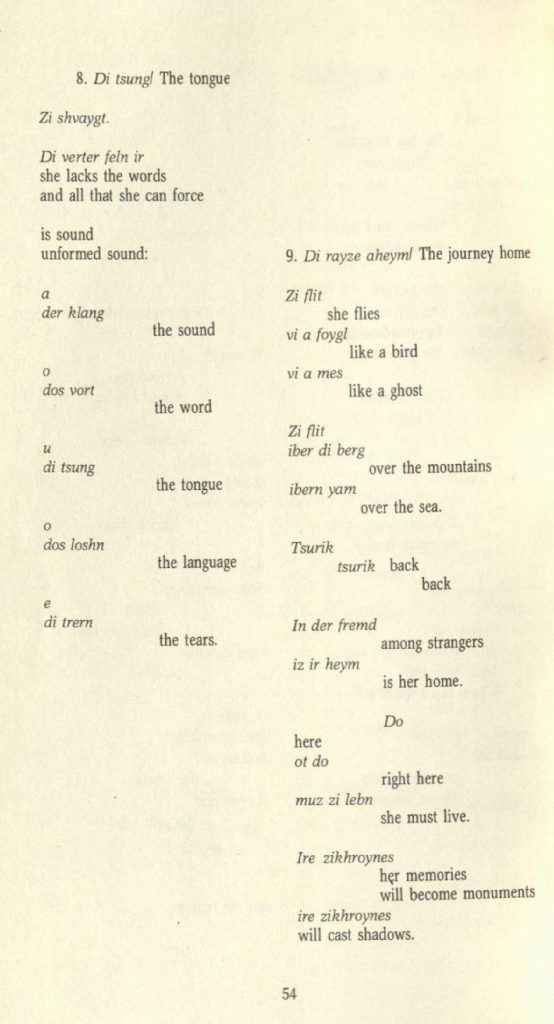

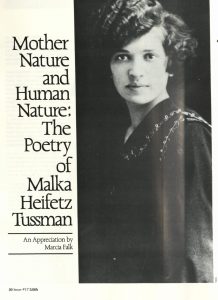

American JEWS. We will kill you all”) to stand-alone slurs (“kikes”). The professor concluded that “these days, the anti-JAP graffiti have been replaced with vile anti-Semitic slogans….people no longer feel the need to hide an anti-Semitic comment behind a JAP joke” (7). Lilith here attends to an important issue that likely would have resonated with a lot of its audience: female college-age and educated Jewish feminists. By demonstrating the connection between sexism, anti-Semitism, and white supremacy, Lilith reinforces the importance of intersectional solidarity in Jewish feminism, while reminding readers that the fight for Jewish women’s safety and equality was not over yet. The author of this article is Marcia Falk, a Jewish educator and poet born into the baby boomer or post World War II generation. Falk celebrates Tussman as a midcentury Yiddish literary figure, activist, mother, and mentor. Tussman, born in the 1890s in Ukraine, wrote poetry and short stories in four languages including Russian, Hebrew, English, and Yiddish. Tussman only began to publish once she moved to Chicago in 1912. Falk first met Tussman at a Jewish arts festival in Berkeley, California, and afterwards began to translate Tussman’s poetry into English. The two women became friends and often exchanged poetry, letters, and recipes. In the summer of 1973, Falk lived in Berkeley with Tussman as they feverishly worked to translate eighty Yiddish poems that were later published as a chapbook (“Am I Also You?” published by Tree Books, 1977). The two women recognized the importance of preserving Jewish women’s literary legacy across time and place, embodying the very virtue of the intergenerationality that Jewish feminists in years to come would regard as necessary to the second-wave struggle.

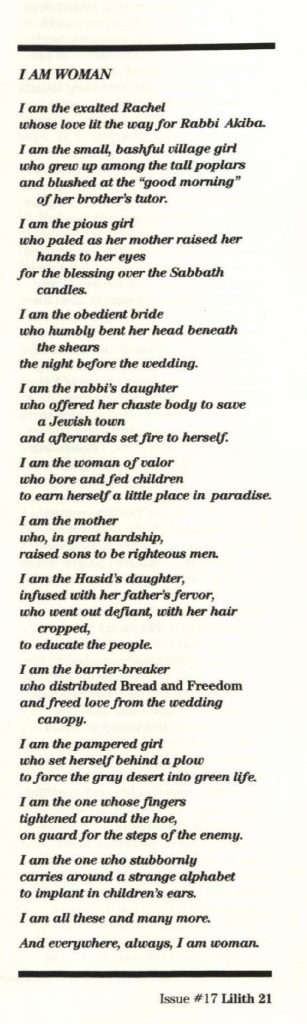

The author of this article is Marcia Falk, a Jewish educator and poet born into the baby boomer or post World War II generation. Falk celebrates Tussman as a midcentury Yiddish literary figure, activist, mother, and mentor. Tussman, born in the 1890s in Ukraine, wrote poetry and short stories in four languages including Russian, Hebrew, English, and Yiddish. Tussman only began to publish once she moved to Chicago in 1912. Falk first met Tussman at a Jewish arts festival in Berkeley, California, and afterwards began to translate Tussman’s poetry into English. The two women became friends and often exchanged poetry, letters, and recipes. In the summer of 1973, Falk lived in Berkeley with Tussman as they feverishly worked to translate eighty Yiddish poems that were later published as a chapbook (“Am I Also You?” published by Tree Books, 1977). The two women recognized the importance of preserving Jewish women’s literary legacy across time and place, embodying the very virtue of the intergenerationality that Jewish feminists in years to come would regard as necessary to the second-wave struggle. There is a turning point in the poem where Tussman writes “I am the mother / who, in great hardship, / raised sons to be righteous men” (24-26). Here, the woman’s power is not derived from the men in her life, but vice versa: part of her mightiness is the ability to raise “righteous” sons despite struggle. Their power originates in hers. After this line, the speaker of the poem declares herself an able rebel, a “barrier-breaker / who distributed Bread and Freedom / and freed love from the wedding canopy” (29-31). “Bread and Freedom” is a reference to Tussman’s work in Chicago’s anarchist-socialist political scene of the 1920s, where she advocated for economic justice and Marxism at the risk of deportation and arrest. This woman seems very different from the “obedient bride” who was exalted earlier in the poem, but is given equal weight, attention, and praise in Tussman’s poem. Tussman begins by honoring traditional women who have worked within the patriarchy and finishes by paying tribute to activist women who engage in the different work of activism. While neither of these types of women seem more privileged or powerful than the other, it is important to note that by finishing the poem with the activist woman, Tussman creates a developmental arc that begins within patriarchal norms and ends outside of such norms.

There is a turning point in the poem where Tussman writes “I am the mother / who, in great hardship, / raised sons to be righteous men” (24-26). Here, the woman’s power is not derived from the men in her life, but vice versa: part of her mightiness is the ability to raise “righteous” sons despite struggle. Their power originates in hers. After this line, the speaker of the poem declares herself an able rebel, a “barrier-breaker / who distributed Bread and Freedom / and freed love from the wedding canopy” (29-31). “Bread and Freedom” is a reference to Tussman’s work in Chicago’s anarchist-socialist political scene of the 1920s, where she advocated for economic justice and Marxism at the risk of deportation and arrest. This woman seems very different from the “obedient bride” who was exalted earlier in the poem, but is given equal weight, attention, and praise in Tussman’s poem. Tussman begins by honoring traditional women who have worked within the patriarchy and finishes by paying tribute to activist women who engage in the different work of activism. While neither of these types of women seem more privileged or powerful than the other, it is important to note that by finishing the poem with the activist woman, Tussman creates a developmental arc that begins within patriarchal norms and ends outside of such norms.