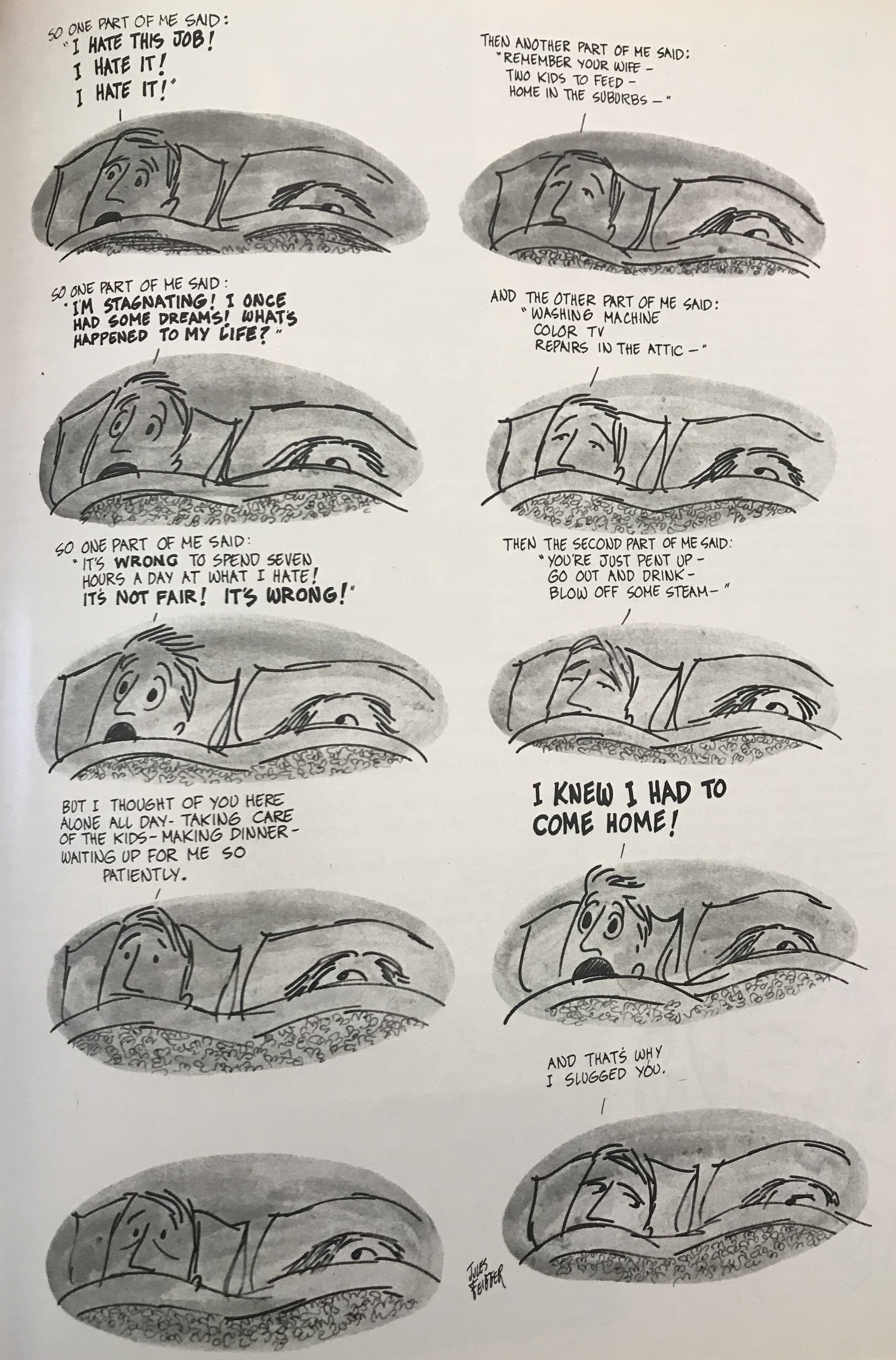

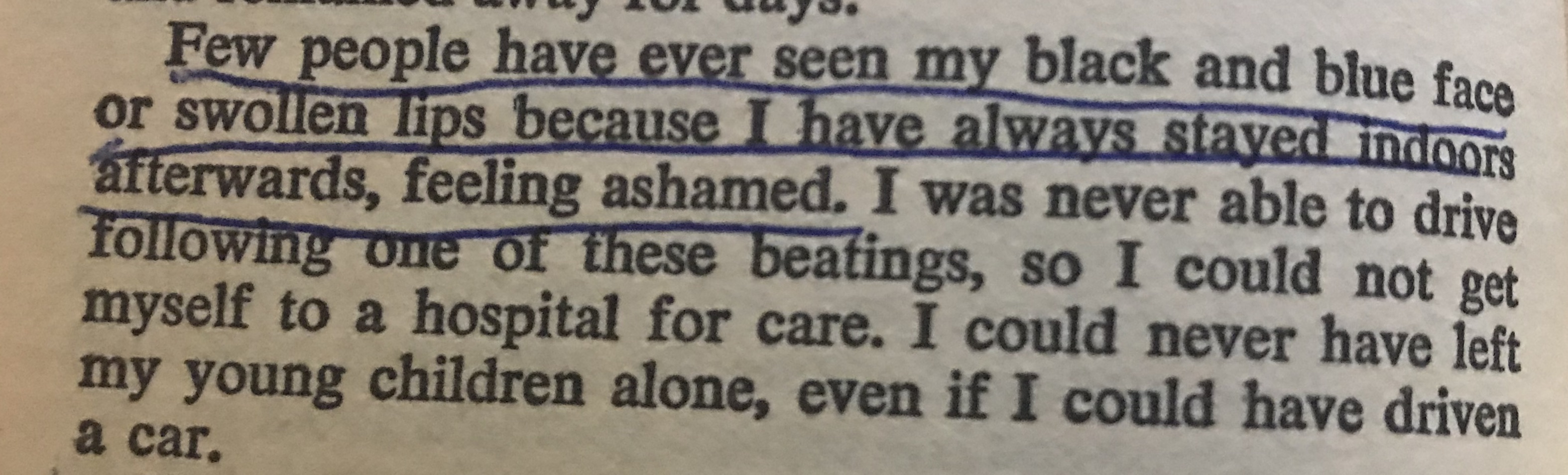

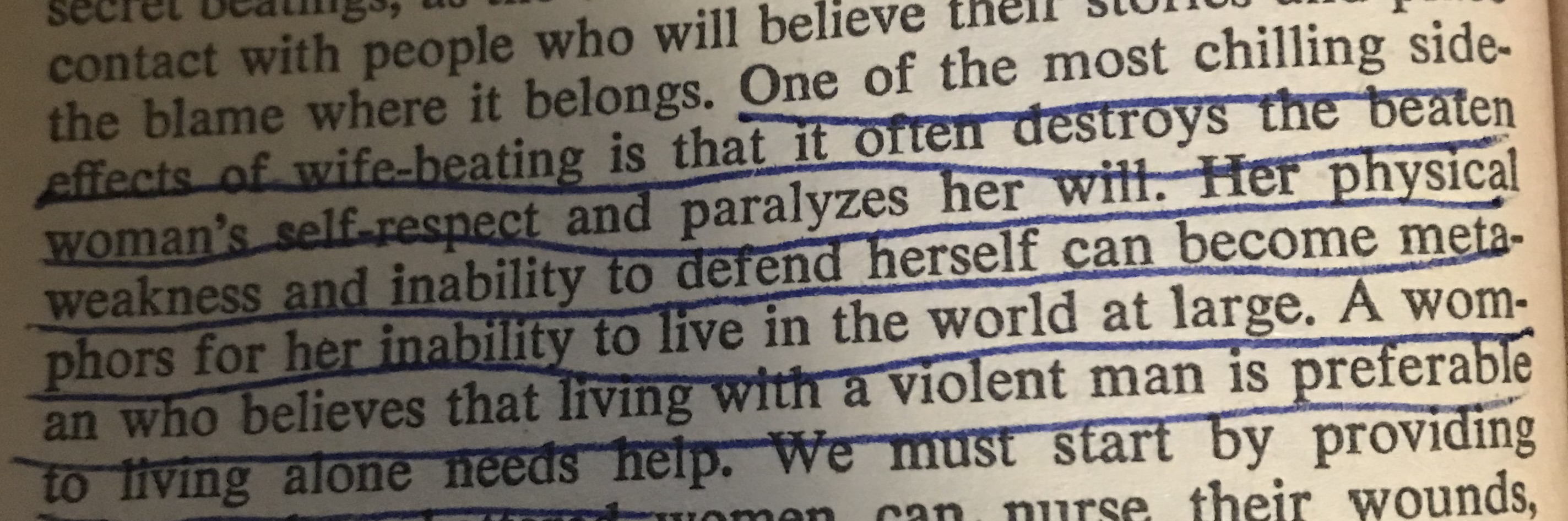

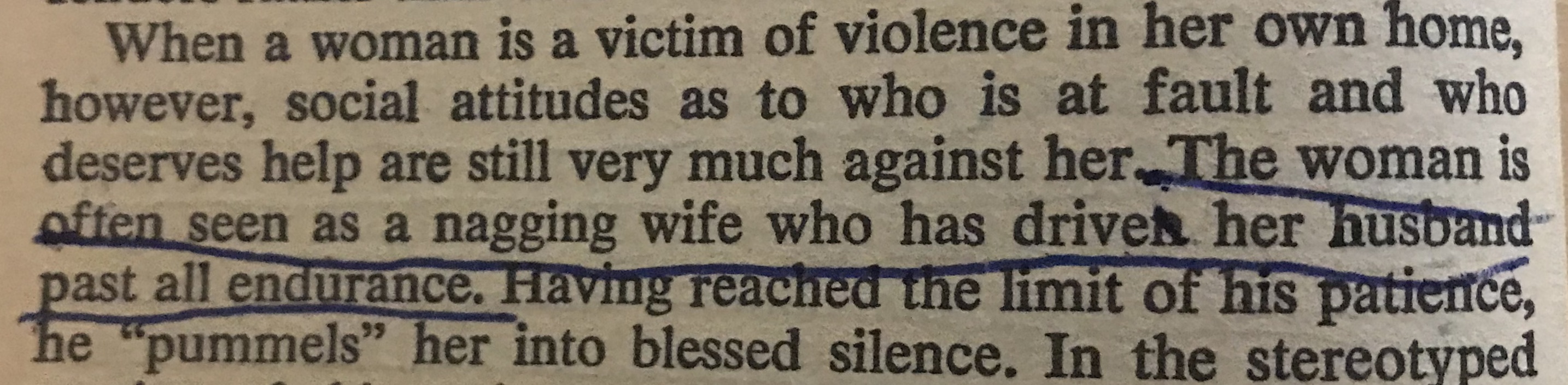

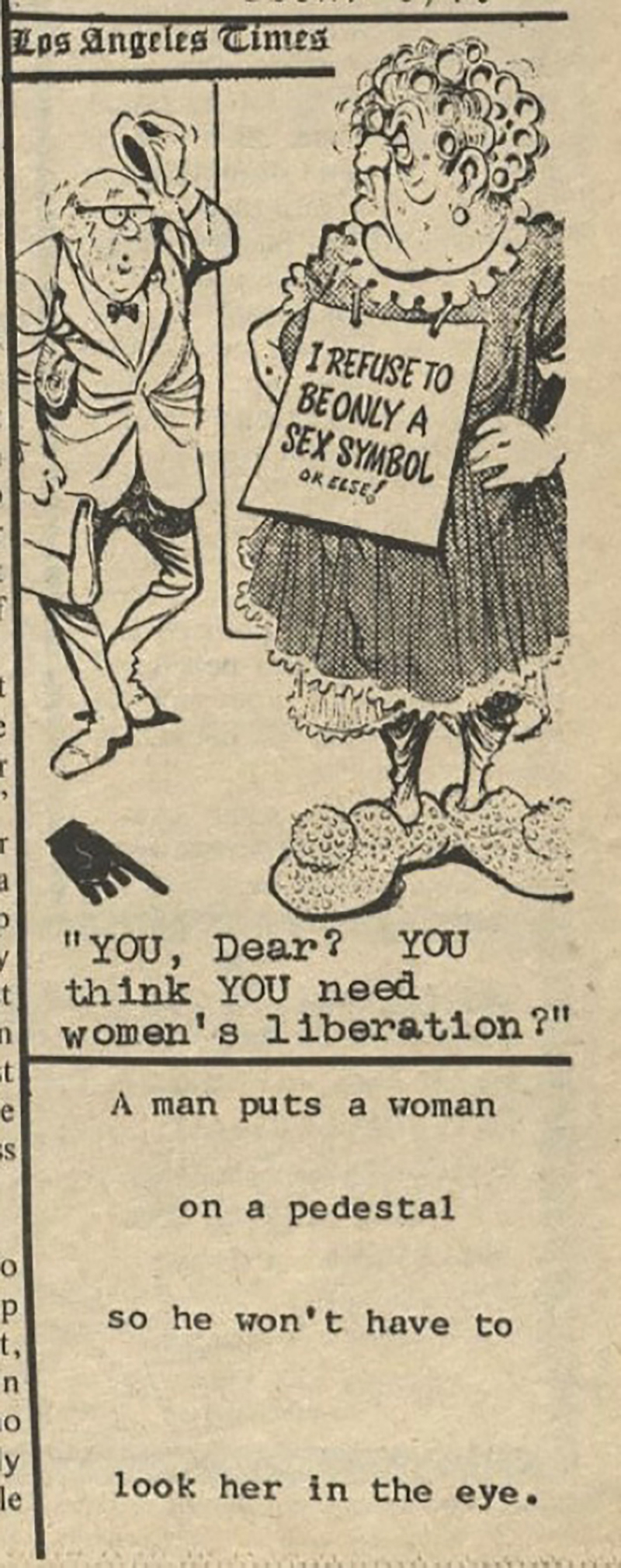

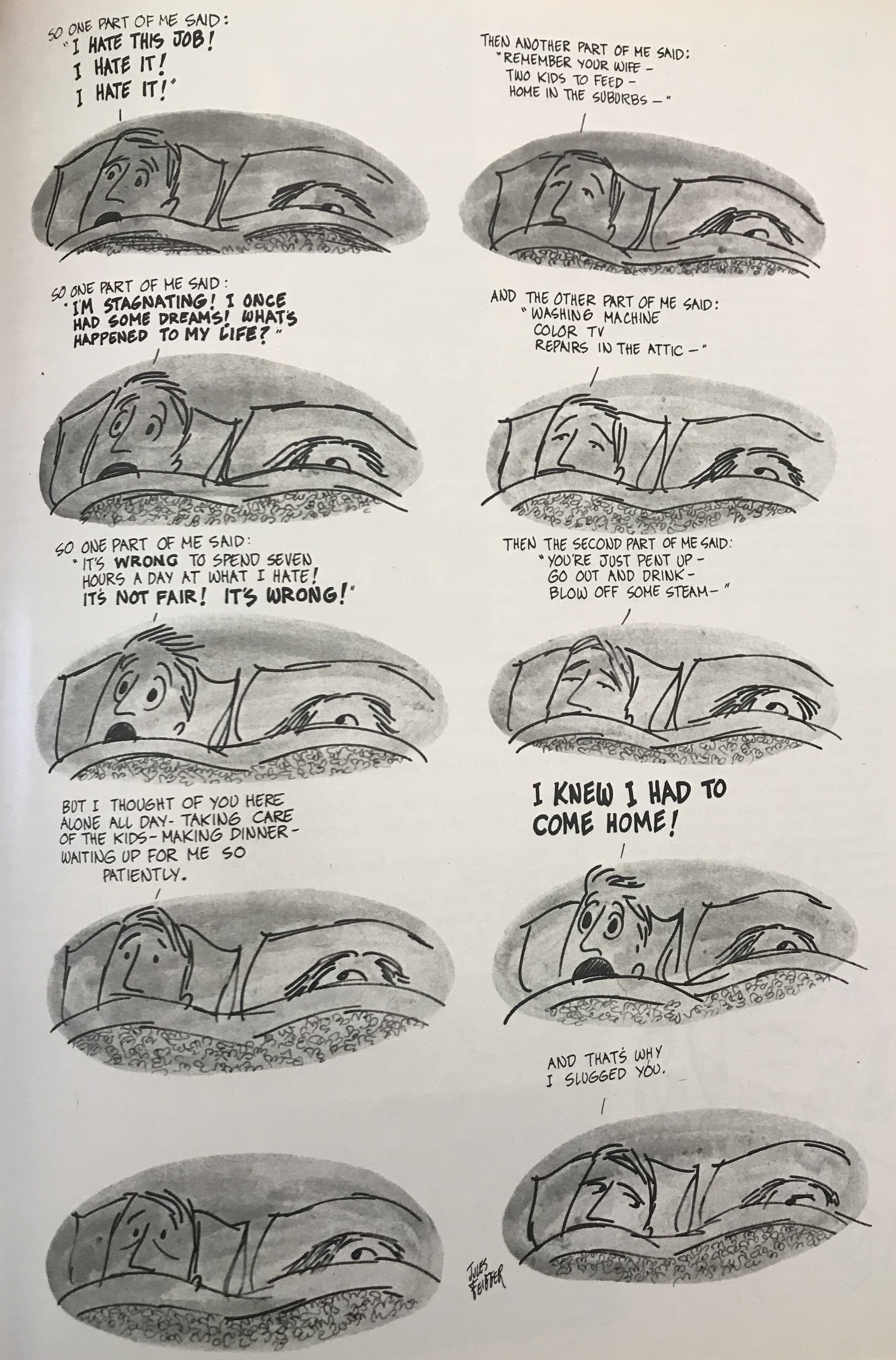

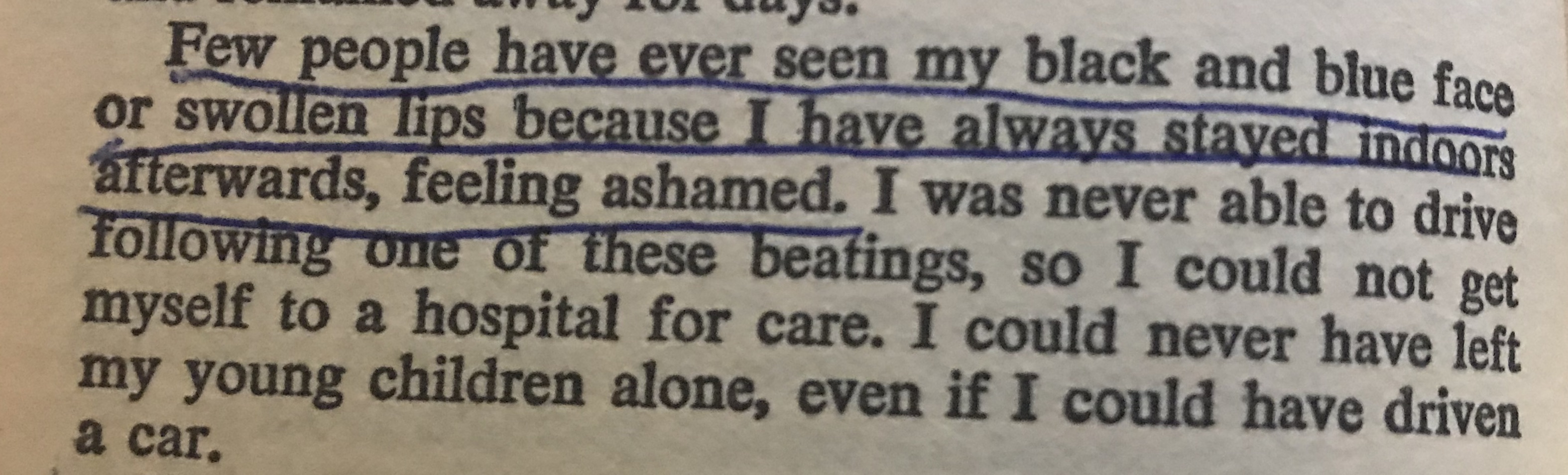

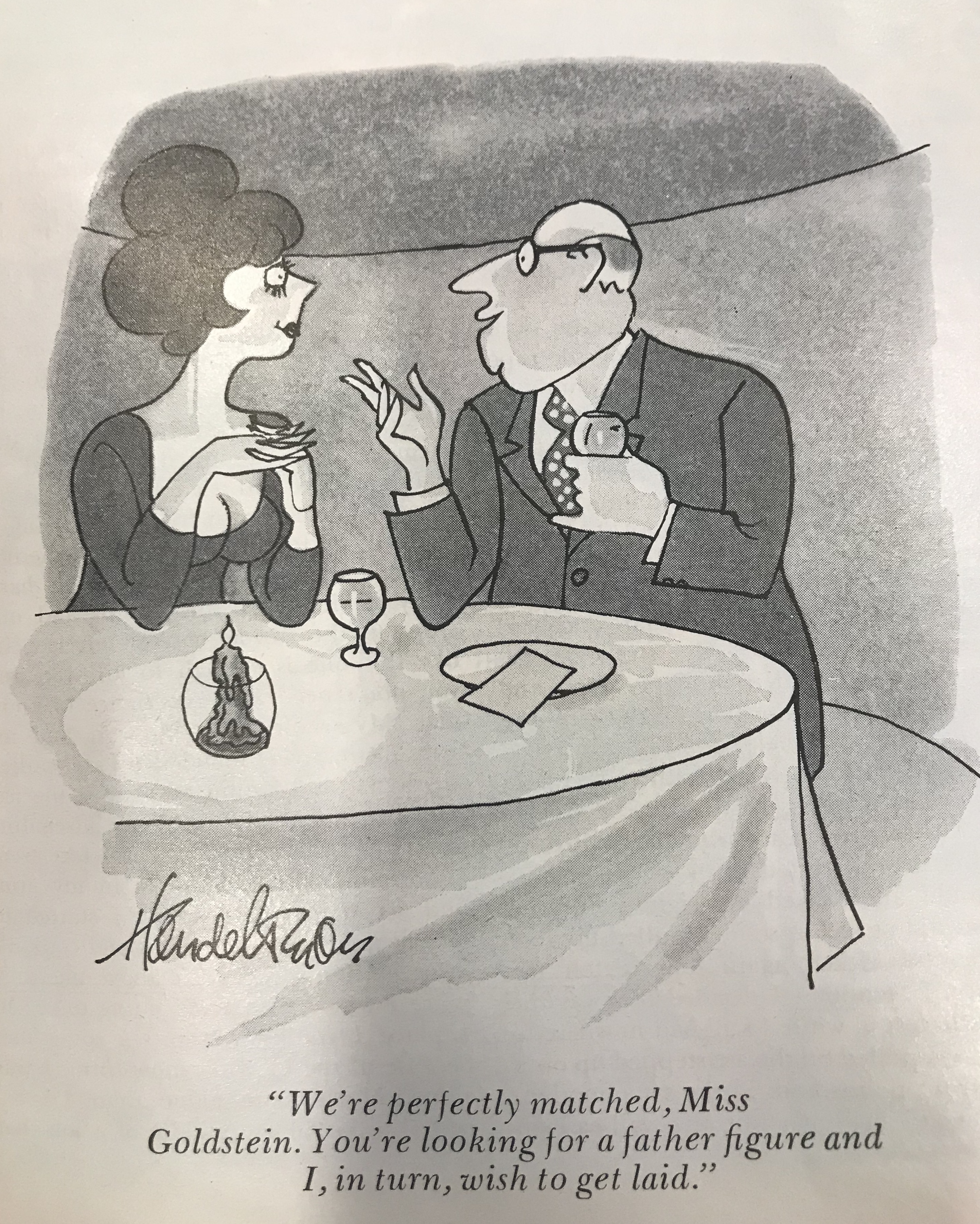

Above is a cartoon from Playboy (vol. 5, no. 10) and an article from The American Women’s Movement titled “Letter from a Battered Wife” that was initially published in Del Martin’s Battered Wives. Both are contrasting portraits of domestic violence. The cartoon is very blunt and unapologetic in its use of an act of violence as a point of humor. The comedic technique being used here is a reframing device. The final line “And that’s why I slugged you” puts both the man and woman’s behavior in the previous panels in a new context. The man’s desire to come home to see his wife is recontextualized as either a desire to relieve stress by beating up another person or to express jealousy of the fact that his wife is not working outside the home and is exempt from the kind of stress he experiences. The woman, meanwhile, conceals her face throughout the comic, and the new context allows the viewer to immediately understand that she most likely is hiding a black eye. If we juxtapose this cartoon with the 1976 “Letter from a Battered Wife,” we can reframe this moment again. Del Martin reminds us of the painful reality of spousal abuse: “Few people have ever seen my black and blue face and swollen lips, because I have always stayed indoors afterwards, feeling ashamed” (Martin, 2). The woman in the cartoon is alone with her husband yet she still hides under the covers. This can be an indicator that she is afraid of her  husband but it may also be an indicator that she is ashamed just like the woman in “Letter from a Battered Wife.”

husband but it may also be an indicator that she is ashamed just like the woman in “Letter from a Battered Wife.”

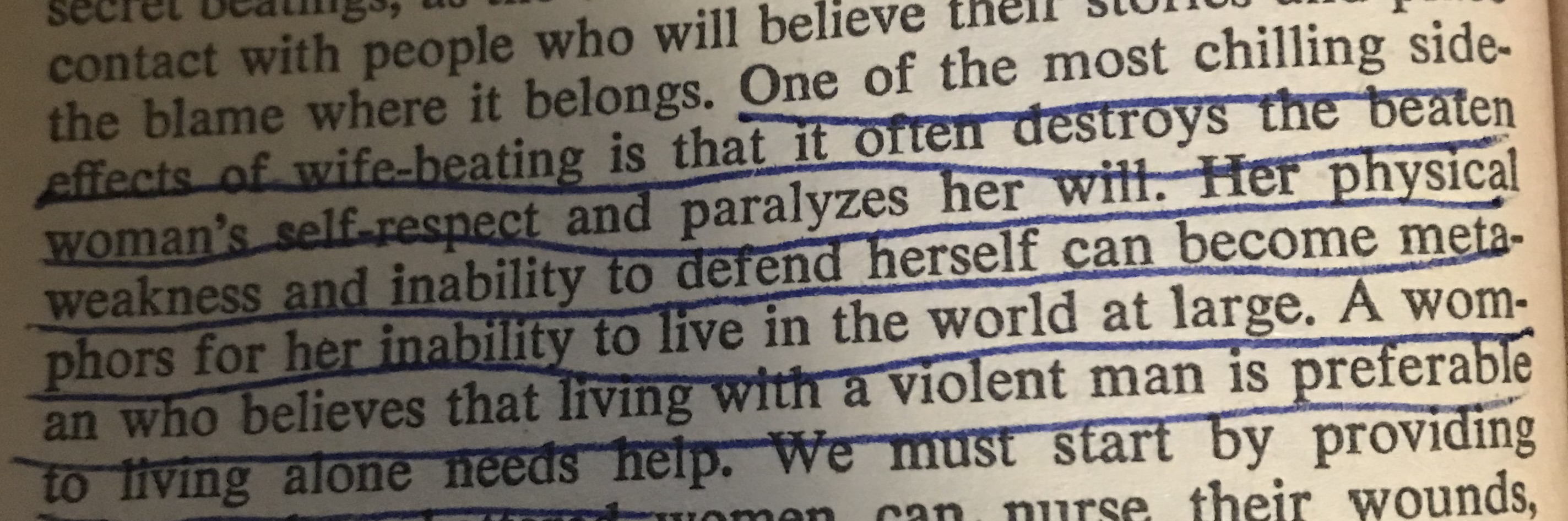

The concealment of the face also reminds the viewer of the isolation victims of domestic violence experience. The letter’s author states that she “cannot depend upon any outside help” because outsiders will “excuse (her) husband for distorting (her) face” but will not “forgive (her) for looking bruised and broken” (Martin, 4). The author goes on to detail this isolation and how it stems from traditional views that no one should interfere with an intimate relationship even if it is abusive. The woman’s lack of movement also reflects the letter’s description of how wife-beating “destroys the beaten woman’s self-respect and paralyzes her will” (Martin, 8). The woman in the cartoon is trapped just like how many victims are trapped.

The dialogue from the man also parallels a commentary made by the author explaining how society’s view of domestic violence often rationalizes the situation as “a nagging  wife who has driven her husband past all endurance. Having reached the limit of his patience he “pummels” her into blessed silence.” (Martin, 6). The husband is stressed and tired in the comic so it is supposed to make sense that he would take it out on his wife.

wife who has driven her husband past all endurance. Having reached the limit of his patience he “pummels” her into blessed silence.” (Martin, 6). The husband is stressed and tired in the comic so it is supposed to make sense that he would take it out on his wife.

The cartoon was published in Playboy in 1958 while the “Letter from a Battered Wife” was published in 1976, in the middle of Second-wave feminism. The letter ends with an optimistic view of how communities are starting to see domestic violence as a grave social problem thanks to organizations like the National Organization for Women (NOW). However, she continues to push the necessity of treating domestic violence as a public issue.

One of the most significant movements within the Second-wave was the Battered Women’s Movement which worked to frame wife-beating as an epidemic that stemmed from a large scale subordination of women (Schneider, 23). These two images display the initial societal views of domestic violence in the 1950s and the attempt change those views in the 1970s. Prior to the movement, domestic violence was not seen as a very big deal and wife abuse was viewed by law enforcers as “domestic disturbances” that were a private matter. Newspapers refrained from even reporting incidents of domestic abuse until 1974 (Pleck, 182). The cartoon’s heavy-handed depiction of violence, even if it is possibly a critique of the husband, reflects the attitude that law and media had towards domestic violence at the time. “Letter from a Battered Wife” is a direct response to these feelings, emphasizing the personal horror victims experience and giving weight to instances of abuse.

Sources:

Playboy, vol. 5, no. 10, HMH Publishing Co., 1958.

Del Martin, “Letter from a Battered Wife.” The American Women’s Movement, 1945- 2000, edited by Nancy

Schneider, Elizabeth M. Battered Women & Feminist Lawmaking. Yale University Press, 2000.

Pleck, Elizabeth H. Domestic Tyranny: The Making of Social Policy Against Family Violence from Colonial Times to the Present. Oxford University Press, 1987.

husband but it may also be an indicator that she is ashamed just like the woman in “Letter from a Battered Wife.”

husband but it may also be an indicator that she is ashamed just like the woman in “Letter from a Battered Wife.”

wife who has driven her husband past all endurance. Having reached the limit of his patience he “pummels” her into blessed silence.” (Martin, 6). The husband is stressed and tired in the comic so it is supposed to make sense that he would take it out on his wife.

wife who has driven her husband past all endurance. Having reached the limit of his patience he “pummels” her into blessed silence.” (Martin, 6). The husband is stressed and tired in the comic so it is supposed to make sense that he would take it out on his wife.

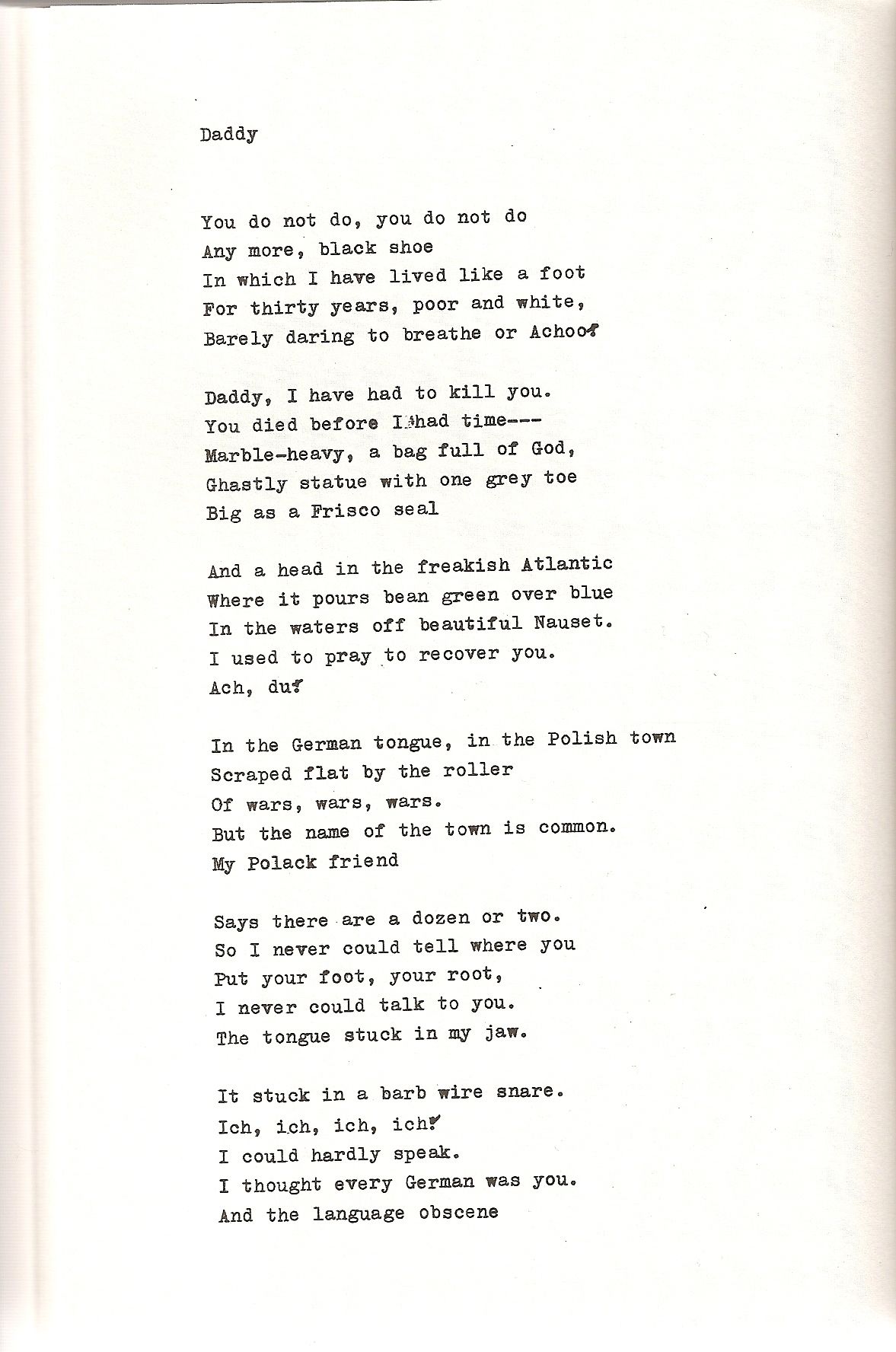

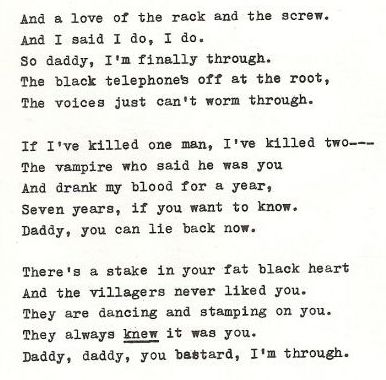

The poem was written on October 12, 1962, the twentieth anniversary of her father’s leg amputation and the day she learned Ted Hughes, her husband, had agreed to a divorce (Platizky, 106). This was also around the time of Adolf Eichmann’s trial and execution, who may be the source of the poem’s Nazi imagery. The poem mixes the personal with the impersonal to paint the father as an evil but beloved figure.

The poem was written on October 12, 1962, the twentieth anniversary of her father’s leg amputation and the day she learned Ted Hughes, her husband, had agreed to a divorce (Platizky, 106). This was also around the time of Adolf Eichmann’s trial and execution, who may be the source of the poem’s Nazi imagery. The poem mixes the personal with the impersonal to paint the father as an evil but beloved figure.