This Bridge Called My Back was one of the first feminist anthologies devoted to representing the voices of women of color. It was first published in 1981 in response to the racism of white feminists in the second-wave feminist movement. This anthology frequently criticizes the lack of solidarity between white women and women of color throughout the movement and highlights the importance of recognizing the intersectionality of identities.

This is the first edition of This Bridge Called My Back. It was first published in 1981.

In their introduction, Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa, the editors of the anthology, note that the process of creating this book led to a “greater solidarity with other feminists of color across the country” (1st edition, xxiv). The anthology soon became a reflection of “an uncompromised definition of feminism by women of color in the U.S.” (1st edition, xxiv). There are now four editions of This Bridge Called My Back, with the most recent edition published in 2015. In the introduction to the fourth edition of the anthology, Moraga emphasizes the importance of political memory in order to ensure that “we are not always imagining ourselves the ever-inventors of our revolution” (4th edition, xix). The continued publication of the anthology serves as a form of political memory that Moraga encourages us to recognize; however, it also calls attention to the following question: Why do we still need to create platforms for women of color in order for their voices to be represented?

Moraga argues that This Bridge Called My Back ought to be considered an “archive of accounts of those first ruptures of consciencia where we turned and looked at one another across culture, color and class difference,” (4th edition, xxiv). However, the ultimate purpose of this fourth edition of the anthology is for “the next generation, and the next one” (4th edition, xxiv). This anthology seeks to create solidarity among women of color and through this edition, across generations. When the first edition was published, it was “created with a sense of urgency” and “from the moment of its conception, it was already long overdue” (1st edition, xxiv). The activists of that time recognized that this “was a book that should already have been in [their hands]” (1st edition, xlv), and, in creating this anthology, they were ensuring the existence of this platform for future women of color.

This is the fourth edition of This Bridge Called My Back. It was published in 2015, making it the most recent edition.

Moraga believes that the women who contributed to the first edition of the anthology would call the next generations their “ ‘familia’– [their] progeny,” entrusting the next generation “with the legacy of [their] thoughts and activisms, in order to better grow them into a flourishing planet and a just world” (4th edition, xxiv). The anthology serves to remind its readers to recognize the efforts made by previous activists and that we cannot expect to see the end of the movement. The introduction lists the deaths of several contributors to the anthology, including the editor Gloria Anzaldúa, both as a tribute to their work and an acknowledgement that their work must be continued. This Bridge Called My Back continues to combat the silencing of women of color within the feminist movement and unites generations of activists.

Sources:

Moraga, Cherríe, and Gloria Anzaldúa, editors. This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color. Persephone Press, 1981.

Moraga, Cherríe, and Gloria Anzaldúa, editors. This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color. 4th ed., State U of New York P, 2015.

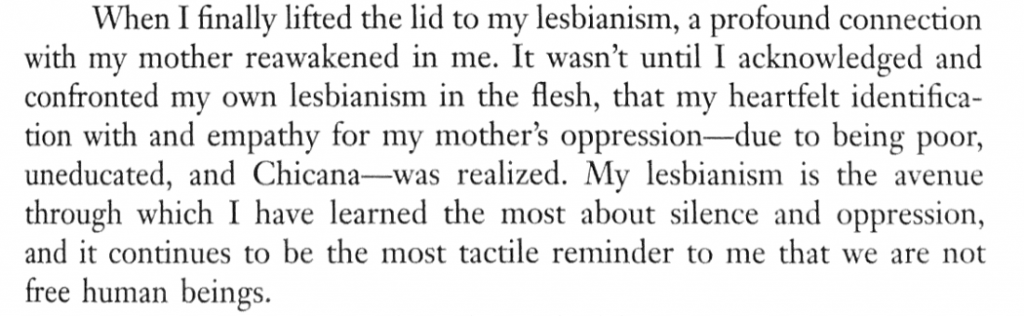

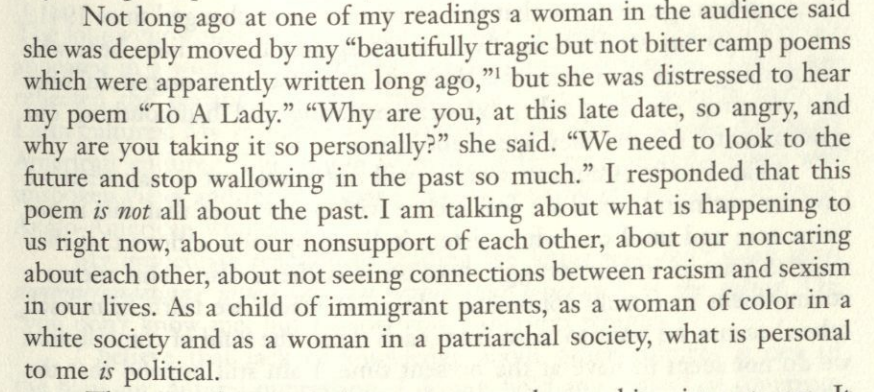

But Yamada argues that different facets of a woman’s identity inform each other. She claims that “as a child of immigrant parents, as a woman of color in a white society and as a woman in a patriarchal society, what is personal to [her]

But Yamada argues that different facets of a woman’s identity inform each other. She claims that “as a child of immigrant parents, as a woman of color in a white society and as a woman in a patriarchal society, what is personal to [her]

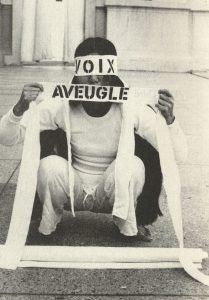

In this letter, Anzaldúa explores her thought process when she writes and recognizes the conditioning she has endured that has discouraged her from writing. As a Third World woman, she had been taught that her speech is inaudible and that this community “speak[s] in tongues like the outcast and the insane” (163). Anzaldúa acknowledges a recurring voice in her that poses this question to her: “Who am I, a poor Chicanita from the sticks, to think I could write?” (164). Through creation, Third World women are defying the beliefs that they are incapable of doing so, a form of power in itself.

In this letter, Anzaldúa explores her thought process when she writes and recognizes the conditioning she has endured that has discouraged her from writing. As a Third World woman, she had been taught that her speech is inaudible and that this community “speak[s] in tongues like the outcast and the insane” (163). Anzaldúa acknowledges a recurring voice in her that poses this question to her: “Who am I, a poor Chicanita from the sticks, to think I could write?” (164). Through creation, Third World women are defying the beliefs that they are incapable of doing so, a form of power in itself.