Native American women are often portrayed in American media through a narrow lens that negates the complexity of their experiences. Paula Gunn Allen of the Laguna Pueblo speaks to misrepresentation in her poem “The One Who Skins Cats,” included in A Gathering of Spirit (“Paula Gunn Allen,” 2021). The poem is preceded by a quote from Tom Rivington, who describes Sacagawea as a woman deeply in touch with nature, who “worshipped the white flowers that grew at the snowline on the sides of tall mountains” (12).

The excerpt from Tom Rivington included at the beginning of Paula Gunn Allen’s poem “The One Who Skins Cats.”

Gunn Allen’s poem is told from the perspective of Sacagawea herself, juxtaposing the perception of a Native woman through the eyes of a man. In the first section of her poem, Gunn Allen names the many facets of Native womanhood: “I am the one who / holds my son close within my arms, / the one who marries, the one / who is enslaved, the one who is beaten, / the one who weeps, the one who knows / the way, who beckons, who knows / the wilderness” (12). In describing Sacagawea’s role as the “legend” as well as the many other roles of “woman” she inhabited throughout her lifetime, Gunn Allen honors the dimensionality of Sacagawea’s character. She is “Slave Woman, Lost Woman, Grass Woman / mountain pass / and river woman,” and she is also “free” (13). The natural world is eternal, ever-changing, and inextricably linked to the power of Native women. Through demonstrating this power within multiple identities, Gunn Allen rejects stereotypical portrayals of Native American women that fail to acknowledge the entirety of their influence. To subject Sacagawea to the image of her face on a coin and only recognize her for one part of her life is to deny her of her personhood. This simplification of experience perpetuates the suppression of Native identity.

In the second part of her poem, Gunn Allen confronts this tendency to generalize

Indigenous stories more directly: “I have had / a lot of names in my time. None / fit me very well, but none was my / true name anyway, so what’s the difference?” (13). Here, Gunn Allen emphasizes the importance of language and referring to people how they choose, by their true name, as it affirms their being-ness. Gunn Allen calls out white women for simplifying the histories of Native women: “Those white women who decided I alone / guided the white man’s expedition across / the world, what did they know? Indian maid, / they said. Maid. That’s me” (13). She goes on to identify white feminism’s exploitation of Native women by using them to advance their own liberation without creating space for them in the Women’s Liberation Movement:

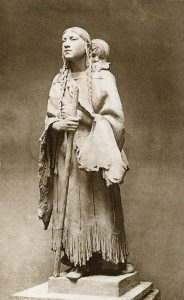

Sakakawea, by Bruno Louis Zimm 1904 .

I lived a hundred years or more / but not long enough to see the day / when those white women, suffragettes, / made me the most famous squaw / in all creation. / You know why they did that? / Because they was tired of being nothing / themselves. They wanted to show / how nothing was really something of worth. / And that was me (14).

By including the history of white women utilizing Native womens’ experiences for the purposes of their own liberation, Gunn Allen highlights how the Women’s Liberation Movement itself appropriated and oppressed women of color who did not have agency over their own narratives. Failing to include Native women in the feminist movement in a way that gives them control over sharing their experiences and telling their own stories has further oppressed Indigenous women.

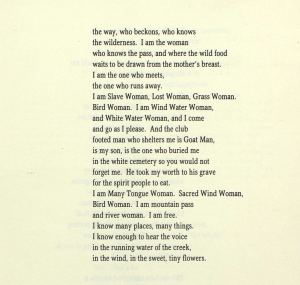

Excerpt from the first half of Gunn Allen’s “The One Who Skins Cats.”

The white feminist romanticization of Sacagawea negates her experience as a Native woman. It fails to address the rejection Sacagawea faced from her own people, who called her names and said she had “betrayed the Indians / into the white man’s hand” (15). Native women bear an immense burden as women of color facing an intersection of injustices from both white women feminists who seek to exploit them and the men in their own communities who blame them as traitors. Gunn Allen works against this paradigm by recounting the lesser-known but equally important story of how Sacagawea fled from her abusive husband (17).

Gunn Allen reiterates the diversity of identity of Native women in her final stanza: “the story of Sacagawea, Indian maid, / can be told a lot of different ways. / I can be the guide, the chief. / I can be the traitor, the Snake. / I can be the feathers on the wind” (17). Gunn Allen exemplifies the importance of interrogating mainstream views of Indigenous women, and more than that, she acknowledges the breadth of roles that Native women take on, whether they fit the stereotype or not. By invoking the voice of Sacagawea to uncover the myth and legend behind her own name, Gunn Allen furthers the Indigenous feminist mission of appreciating the full, intersectional experiences of Indigenous women.

Sources:

Brant, Beth. Sinister Wisdom: A Gathering of Spirit, no. 22/23, Iowa City Women’s Press, 1983.

Gunn Allen, Paula. “The One Who Skins Cats,” Sinister Wisdom: A Gathering of Spirit, no. 22/23, pp. 12-17.

“Paula Gunn Allen.” Wikipedia, 17 November 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paula_Gunn_Allen.

Zimm, Louis Bruno. Sakakawea. 1904, The University of Montana, Missoula, http://www.lewis-clark.org/article/2492.