In her essay “Asian Pacific American Women and Feminism,” Mistuye Yamada addresses a common issue faced by women of color during the feminist movement: the struggle of maintaining both your identity as a woman and as a person of color. Yamada explains how women of color are often expected to earn their place in the feminist movement, whereas white women maintain an entitlement to that space. This document examines the exclusion of the voices of Asian American women and other Third World women from Second Wave feminism.

https://tableau.uchicago.edu/articles/2017/05/poetry-mitsuye-yamada

And Yamada recognizes the efforts of feminist organizations that strive to include women of color. However, she argues that these efforts are motivated by the need to appear inclusive, when in reality, women of color included in these organizations are often used as “tokens” (69). Consequently, women of color are used to claim diversity and inclusion, but are not actually listened to when they express their concerns. Women of color have to fight for their place in the feminist movement, but even once they achieve it, their voices continue to be ignored. Yamada explores that sentiment when she claims that every time she speaks in front of an audience it is as though she were “speaking to a brand new audience who had never known an Asian Pacific woman who is other than the passive, sweet etc. stereotypes of the ‘Oriental’ woman” (68). Stereotypes associated with these communities unconsciously invalidate the activism of women of color.

Yamada explains that when women of color are invited into feminist organizations, they are expected to educate white women on their experiences with oppression. However, when they are asked to speak about their experiences, they are “expected to move, charm or entertain, but not to educate in ways that are threatening to [their] audience” (68), who are predominantly white women. Women of color are burdened with the responsibility of educating white women about their experience but in ways that don’t make their white audience uncomfortable. This form of emotional labor forces women of color to accommodate to white women, thus contributing to a hierarchy within the feminist movement. Even though their participation in feminist organizations creates an illusion that women of color are officially invited into the movement, their experiences continue to be silenced, Yamada argues.

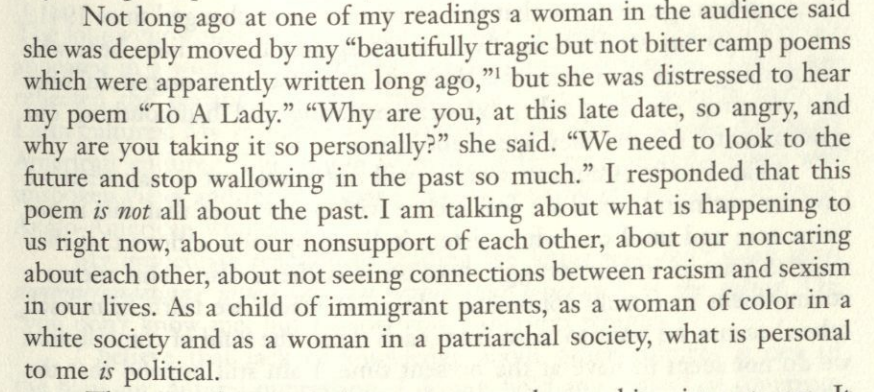

Many activist women of color are accused of placing their “loyalties on the side of ethnicity over womanhood,” (69) because of their participation in groups that promote ethnic identity, illustrating that these women are expected to choose between their identities in order to validate their voice in the movement. But Yamada argues that different facets of a woman’s identity inform each other. She claims that “as a child of immigrant parents, as a woman of color in a white society and as a woman in a patriarchal society, what is personal to [her] is political” (71).Yamada argues that the relationships between her identities are something that white feminists ought to understand because they establish her acceptance in society. Because of her identities, Yamada is constantly treated as a guest in the home of the dominant group, whether that be in the feminist movement, as a speaker, or as a resident of a neighborhood. When she began advocating for her Fair Housing Bill in the 1960s, for instance, her friends at the neighborhood church asked her, “Why are you doing this to us? Haven’t you and your family been happy with us in our church? Haven’t we treated you well?” (71). These questions illustrate that she is not fully accepted in these communities. Instances such as these explain the distrust found between white women and women of color. Yamada demands that “until our white sisters indicate by their actions that they want to join us in our struggle because it is theirs also,” (72) women of color will not be able to fully participate in the feminist movement. Although Yamada was calling attention to the distrust that pervaded the second wave feminist movement, similar sentiments continue to persist, limiting the ability to establish solidarity among women.

But Yamada argues that different facets of a woman’s identity inform each other. She claims that “as a child of immigrant parents, as a woman of color in a white society and as a woman in a patriarchal society, what is personal to [her] is political” (71).Yamada argues that the relationships between her identities are something that white feminists ought to understand because they establish her acceptance in society. Because of her identities, Yamada is constantly treated as a guest in the home of the dominant group, whether that be in the feminist movement, as a speaker, or as a resident of a neighborhood. When she began advocating for her Fair Housing Bill in the 1960s, for instance, her friends at the neighborhood church asked her, “Why are you doing this to us? Haven’t you and your family been happy with us in our church? Haven’t we treated you well?” (71). These questions illustrate that she is not fully accepted in these communities. Instances such as these explain the distrust found between white women and women of color. Yamada demands that “until our white sisters indicate by their actions that they want to join us in our struggle because it is theirs also,” (72) women of color will not be able to fully participate in the feminist movement. Although Yamada was calling attention to the distrust that pervaded the second wave feminist movement, similar sentiments continue to persist, limiting the ability to establish solidarity among women.

Sources:

Yamada, Mitsuye. “Asian Pacific American Women and Feminism” This Bridge Called My Back, edited by Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa, 4th ed., State U of New York P, 2015, pp. 68-72.