The glamorous world of the show business attracts a large audience, and for a good reason. The combined effort and talent of the playwright, actors, directors, and set designers can produce a beautiful product: awe-inspiring shows. But why are humans so captivated by entertainment? Not everyone has the knowledge and experience to appreciate or criticize entertainment the way professional show or movie critics do. For most people, it is simply because they enjoy the experience. That is, they leave the play feeling better than how they arrived. Many plays (and movies, for that matter) offer the viewers a picture of a better, more perfect world than the one in which they actually live. Richard Dyer, in his essay “Entertainment and Utopia”, writes that entertainment, specifically show business, present elements of the utopian through the plotline, characters, set, and music, in a way that enthralls the audience; they can temporarily enter into an idealized world. This appears in Wicked The Musical, most obviously during the song “Defying Gravity”, when Ephaba rises from the stage, suspended in mid air, surrounded by artificial fog, as she sings about about her newfound power and freedom. Wicked attracts a worldwide audience because it tells a story about love, true friendship, and valuing others for who they are at the core, not on the surface. But could there be a different type of entertainment that succeeds without offering an idealized version of the world? A type that still attracts crowds, but possibly for different reasons? In an alternate type of entertainment, realism replaces utopianism, and the world on stage allows the viewer to acknowledge and relate to the universal experience of humans as we are, rather than the idealized vision of how we would like to be.

In the play, The Humans (New York opening 2016), written by Stephen Karam and directed by Joe Mantello, we enter the lives of the Blakes, a middle-class American family, during their Thanksgiving celebration. The play takes place in the new home of Brigid Blake (Sarah Steele) and her boyfriend, Rich (Arian Moayed), in their tiny, two-story Manhattan duplex. But as with many family get-togethers, any seemingly ordinary event can quickly turn into a nightmare. A sudden influx of familiar faces revives past arguments, and provides an open-mic for honest, and sometimes harsh, opinions. Throughout the course of the play, the multi-layered complexities of the Blakes unravel and the tension grows until they reach their breaking point. In the opening scene, Brigid’s family arrives from Scranton, Pennsylvania. Her father, Eric (Reed Birney), her mother, Deirdre (Jayne Houdyshell), her sister, Aimee (Cassie Beck), and her grandma, Momo (Eric’s mother, played by Lauren Klein) who has dementia and resides in a wheelchair, all eventually settle into the less-than-homey apartment. The couple, Brigid and Rich, have not completely moved in yet, so the already dreary apartment looks especially barren and “a touch ghostly” on this Thanksgiving evening. The set includes a narrow metal spiral staircase that connects the top floor to the basement, and a folding table with plastic chairs. Someone hung a singular string of Christmas lights over the kitchen in attempt to brighten the permanently dull space. The apartment is nothing special, and everyone in the audience recognizes the characters as ordinary, middle-class human beings.

What good is a play that depicts an ordinary world in which nothing seems exciting or amusing? In other words, what are we, as the audience, to gain by watching this play? It does not captivate us for its grandiose music, costumes, or sets in the way that other plays do. Jill Dolin in Utopia in Performance: Finding Hope in Theater writes that utopian entertainment “calls the attention of the audience in a way that lifts everyone slightly above the present, into a hopeful feeling of what the world might be like if every moment of our lives were as emotionally voluminous, generous, aesthetically striking, and intersubjectively intense”(5). Rather than depicting “what the world might be like” or what humans could be like, realism appeals to an audience for another reason. It allows us to focus in on a universally relatable topic: what it means to be human. Nothing in the play, no songs, sound effects, costumes, or anything within the realm of the utopian, distracts the audience from this because they do not exist. The director, Joe Mantello, and set director, David Zinn, successfully make the set of the play so common and generic, so real, that the audience forgets that these people are actually actors in a play, not just, say, our next-door neighbors. The audience feels at home with the Blakes, they welcome us into their family holiday to be a part of their evening. The Blake’s world is our world, and as they become more and more real, their lives on stage take on the characteristics of our lives: unstaged and unscripted

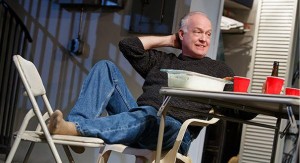

From left to right: Eric, Deirdre, Aimee, Brigid, Rich

Certain sentiments arise in the play that undeniably relate to most humans. For example, the feeling that life is a never-ending list of chores and responsibilities. Eric and Deirdre have worked for decades in the same jobs, as a school maintenance worker, and as a office manager at a firm, respectively. Despite their many years of work, they still face financial insecurity. Eric says “I’ll tell you, Rich, save your money now. I thought I’d be settled by my age, you know, but man, it never ends. Mortgage, car payments, Internet, our dishwasher just gave out”. Karam does a wonderful job capturing how difficult it is for people to make ends meet. Another source of disagreement springs from Eric and Deirdre’s interactions with their daughters in sort of battle between generations. Even the location of their homes shows a divide. Brigid has just moved to the glamorous New York City, while Deirdre and Eric live in suburban Scranton, Pennsylvania. Additionally, they are devout Christians who constantly nag their daughters for their disinterest, which is made obvious when Brigid says, “no religion at the table!”. Eric says to Brigid, “you put your faith in juice cleansing…”, in another stab at the younger generation. And Deirdre makes her point crystal clear when she gives the young couple a statue of the Virgin Mary as a housewarming gift. Another disagreement arises between Brigid and Deirdre, who cannot for the life of her understand why Brigid and Rich have not gotten married yet! Never missing an opportunity to bring it up, Deirdre responds to Brigid’s reference to her “mother-in-law” by saying under her breath, “She isn’t your mother unless you get married”. Furthermore, Eric stigmatizes mental illness and refuses to pay for Brigid’s therapy, despite her constant insistence on needing it. “Well, save some of the money you spend on organic juice and pay for it yourself” he says to Brigid, a harsh response, indicating clearly their differing views. These interactions between the family members on stage feel all too real to us audience members. The ability to relate to to these characters almost has an effect of breaking down the fourth wall between the audience and performers, as if we are present in the room with them.

The Humans reaches another level of realism through its use of humor. Despite the dark reality that this play depicts, Karam still manages to incorporate humor into the script, and its response by the audience is both expected and puzzling at the same time. At the dinner table, Eric asks Rich if he takes medication for his mental illness, because “in our family, we don’t have that sort of depression”, to which Aimee responds “yeah, no, we just have a lot of stoic sadness”. The audience, myself included, laughed. Moreover, Deirdre sends articles to her family via text and email all the time, mostly articles about faith and homosexuality (because Aimee, the elder daughter, is gay). Brigid, annoyed with her mother’s constant messages says, “you don’t have to text her [Aimee] every time a lesbian kills herself”. The audience responded to that remark with a kind of uncomfortable laugh. But how can we justify laughing at these topics? Depression, sexuality, and suicide are serious matters that hit uncomfortably close to home for so many people, so why did we laugh? In The Culture Industry, Adorno explains that “there is laughter because there is nothing to laugh about. Laughter, whether reconciled or terrible, always accompanies the moment when a fear is ended” (112). Similarly, The Freudian Relief Theory states that “laughter is a physical manifestation of the release of nervous energy” (Bardon, 9). Maybe one of these theories can offer some insight as to why human’s response is laughter, since undoubtedly some element of fear or anxiety associated with these topics exists. Karam understands the human aspect of it; what provokes genuine laughter, but also what the effect of this laughter is. When an actor said something, everyone in the audience laughed together, along with the characters who chuckled on stage. In the presence of discomfort or fear, everyone responded the same way through laughter. The shared laughter creates solidarity between audience members. In a sense, laughter in this play brings people closer together into a community of shared experiences, shared fears, and shared anxieties.

The small gestures, subtle remarks, and dark humor that feel so genuine to us point to an even bigger picture of humanity. According to Karam, The Humans explores the “big existential horrors of life that everyone deals with”(Lecture Series), and the Blakes perfectly embody these “horrors”. After years of facing financial difficulties, Eric asks the heart-wrenchingly revealing question, “Don’tcha think it should cost less to be alive?” Not only Eric feels hopeless about life. Aimee faces the possibility of being fired from the law firm where she has worked for years. Even more, her ulcerative colitis has worsened and she may need surgery. And on top of all of this, she is heartbroken over a recent breakup with her girlfriend. How’s that for perfect timing? In utopian entertainment, a character might resolve his/her issues on the premise of the saying, when life gives you lemons, make lemonade. Take Forrest Gump, for example. In this utopian world, he never meets a challenge he cannot overcome. But the overriding message in The Humans reflects the more realistic sentiment that when life gives you lemons, it is awfully difficult to make lemonade. Forrest Gump survives a war, makes millions as a shrimper, and runs across the country with few, if any, setbacks. Eric Blake cannot even retire. If utopian entertainment offers its viewers impossibilities, why not look to realism for a better understanding of what is possible?

People are drawn to entertainment that offers a more perfect world, but in analyzing The Humans, it becomes clear that Stephen Karam sees greater value in representing the real world. The play offers satisfying and refreshing depiction of reality. No sugarcoating, just true hard life. So, to return to my question, what are we, as the audience, to gain by watching this play? The answer is a greater understanding and appreciation for humans, with all of our imperfections. By using realism rather than utopianism in his play, Karam offers us a greater understanding of ourselves, the humans around us, and the world in which we live.