By Dew Panalee Maskati

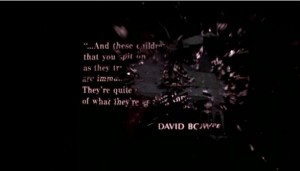

Pop culture was in it’s prime during ‘80s America, with the release of popular classics such as “Karate Kid” and “The A-Team”, and the advent of synthesisers and digital recording in music. It was the age of self-reinvention and rising consumerism — glamour, now on sale at your nearest mall — laced with political turmoil, increasing unemployment rates, rising inflation, and xenophobia. It was in this spirit of dissatisfaction and idealism that “The Breakfast Club” was made. Five high school tropes —“athlete” Andrew, delinquent Bender, Brian the “brain”, “basket case” Allison, and “princess” Claire— overcome their initial aversion to each other to unite in friendship and defy the disciplinarian, Mr. Vernon; they are armed, of course, by the teen rebel’s trustiest weapons: drugs and rock and roll. From its opening title, ‘The Breakfast Club’ establishes itself as a patron of rebellion by paying homage to David Bowie, the nullifier of category and God of self-reinvention, with an excerpt from “Changes”:

“And these children

that you spit on

as they try to change their worlds

are immune to your consolation

they are quite aware

of what they are going through”.

These lines highlight how the movie corroborates the image of the defiant and heroic teen rebel — the counter-culture revolutionary yet untainted by the adult world — and in consequence, is full of vicarious appeal to the teenager’s angst-filled heart. But the movie’s premise and resolution is entirely a fabrication, a fact made visually apparent in the opening sequence, as the camera zooms in beyond the shattering black television screen, and draws us into a realm beyond reality. This heartwarming tale is, in effect, a mask for an underlying, sinister ideology, one gets the viewer to think more favourably of conformity by marketing it as unity. Tropes aren’t transcended; rather, certain accepted stereotypes are subliminally reinforced over others.

The opening title sequence

These stereotypes are so pervasive that the students do not formally learn each other’s names until half-way through the movie. As soon as they do, further labelling is generated: “Claire” is a “fat girl’s name”. Bender as a human being “may as well not even exist in this school”, as Andrew says, because in the eyes of others he is but the stereotype of a criminal. Certain issues remain unaddressed, and are subsequently reinforced, such as male chauvinism: Bender, looking to “impregnate” Claire, does have his wish granted – they fall in love – Claire “couldn’t ignore [him] if [she] tried”. The movie is unsuccessful even in its self-proclaimed mission — abolishing high school stereotypes — because in their final moments of detention, the teenagers each dance in a style that parodies their tropes. Some might interpret this as a euphoric moment of acceptance, but really, it soberingly demonstrates a lack of change — these teenagers still conform.

These stereotypes are so pervasive that the students do not formally learn each other’s names until half-way through the movie. As soon as they do, further labelling is generated: “Claire” is a “fat girl’s name”. Bender as a human being “may as well not even exist in this school”, as Andrew says, because in the eyes of others he is but the stereotype of a criminal. Certain issues remain unaddressed, and are subsequently reinforced, such as male chauvinism: Bender, looking to “impregnate” Claire, does have his wish granted – they fall in love – Claire “couldn’t ignore [him] if [she] tried”. The movie is unsuccessful even in its self-proclaimed mission — abolishing high school stereotypes — because in their final moments of detention, the teenagers each dance in a style that parodies their tropes. Some might interpret this as a euphoric moment of acceptance, but really, it soberingly demonstrates a lack of change — these teenagers still conform.

However, the movie goes beyond this: it seeks to favourably portray the elimination of diversity — more specifically, to see stereotypes deigned unacceptable by society abolished. Let’s take, for example, the outcasts Allison and Bender: due to social conditioning that encourages wariness when confronted by nonconformists, their crude, sexual language and atypical manner, initially gave them the most disdain from other characters and viewer alike. Claire’s response to Bender’s graphic description of sex is to ask “do you want me to puke?”. Allison, on the other hand, embodies the uncivilised: feral behaviour; wild appearance; her endorsement of the “mountains”, “Afghanistan or Israel” over the Chicago “streets”. Yet, they are the most perceptive of all the characters. It is the distance between them and society that cultivates comments such as Allison’s iconic “it’s unavoidable, it just happens… when you grow up your heart dies”, or the critical eye on social convention that leads to Bender’s rejection of Claire’s ability to apply lipstick with her breasts — a bourgie talent that highlights her superficiality and privilege. The others reject their discomforting comments: Andrew has been socially conditioned to interpret Bender’s insight as “insult” when Bender is really just “being honest, asshole!”.

Allison presciently realises that there is no escape from being labelled, by pointing out that once Claire reveals the truth behind her enigmatic sex-life, she will be skewered by a triple-pronged sword: categorised as either a “prude”, “slut” or a “tease”. And indeed, rather than a movement towards acceptance of their quirks, the movie sees Allison and Bender normalised into socially acceptable stereotypes. Allison is given a makeover that turns her into a cookie-cutter doll — note the aggressive way in which she is made to conform through makeup — “don’t stick that in my eye”. She only truly receives Andrew’s approval — “it’s good” — after the transformation. If she had outwardly remained a “basket case”, would Andrew have kissed her? Bender’s indoctrination is less explicit: he puts on Claire’s earring, a trinket from the upper classes. So yes, “The Breakfast Club” does champion acceptance — but only at the price of individuality. Mr. Vernon’s obviously devilish character masks the true evil in the movie: Andrew and Claire, instruments of a cultural ideology that instills “sameness”.

Allison’s makeover

Let’s explore this dichotomy a bit further: students are good and adults, evil. Mr. Vernon’s character actualises the quasi-dictator that haunts every student’s educational experience; more importantly, he embodies Althusser’s “educational state apparatus” and elements of the “repressive state apparatuses” — instruments within a system of oppression (society) that seek to excise individuality and maintain the existing social order by doing so. He shares in their dehumanising methods when he snaps his fingers and repeats commands at Andrew as if to a dog, and exercises their repressive violence through language that goads and humiliates. To the other students: “look at [Bender], he’s a bum”. “What’s the matter, John? You gonna cry?”. The other prominent adult, Carl the janitor, has a characteristic that, at first glance, seems to spare him from the general criticism: he understands. Although an incongruously angelic figure in the prison-like school, what he says bears a disconcerting semblance to totalitarian propaganda from the likes of George Orwell’s “1984”: “I listen to your conversations — you don’t know that but I do”; “I am the eyes and ears of the institution”. Add to this his identification with the lower classes — “you guys think I’m some untouchable peasant… serf” — and he has, in effect, become the voice of Adorno’s “culture industry”. Therefore, the audience is disinclined to sympathise with them.

Since the audience directs its sympathy according to human-object interaction, the objects in the movie reinforce the contest between vessels of a repressive culture (adults) and adolescent resistance. Objects antagonise Mr. Vernon multiple times: to the students’ and the viewer’s amusement, he is proved wrong (and importantly, Bender proved right) when the chair meant to hold open the door springs out of position, thereby granting the teenagers their privacy. Other slapstick instances include coffee spilling over his table, and, unbeknownst to him, toilet paper dangling out of his pants. On the other hand, objects function harmoniously with the students; they reinforce the viewer’s support for the teenagers’ cause. The viewer too, feels victorious when Bender scales the mountain of school supplies to escape solitary confinement. But beyond this, the objects are implementing an equally important task on the viewer’s subconscious: the cues that polarise teenagers against adults have created a battlefield of the school building — a stomachable replica of the ‘Nam, bringing to mind public fear during the Cold War. The students utilise tactics of guerrilla warfare to combat Mr. Vernon — stealth when avoiding him, and “fire and movement” strategy when Bender distracts for the others’ safety.

Dominant during the 1980s was general disgruntlement with the shortcomings of liberal government (the old order) and a favourable view of modern conservatism. National industries faced losses, increased layoffs; Japanese technology and products outstripped the West’s. The Cold War reached its apex, and the generally displeased public agreed with Reagan’s claim that Carter’s liberal government should have chosen to, but did not, “stay the course” in regards to Vietnam. This political divide pervades the movie: the teenagers and adults represent two existing orders, the new and the old, which are at war; its battle ground, the classroom. Mr. Vernon says as much: “these kids have turned on me”. Ultimately, the teenagers emerge victorious: free to do what they please from the second half of detention onwards, Mr. Vernon’s authority ultimately overturned, and stronger in their unity. Andrew gives a strikingly industrial description of his dad as “this mindless machine” programmed to “Win! Win! Win!” that he proceeds to reject; here again, is the dismissal of an archaic, ineffective order. Therefore, the movie’s heartwarming ending insinuates triumph of a new, conservative order over the old — conforming to public sentiment that perceived a weak, ineffective, liberal government. By guiding the audience firmly onto the teenagers’ faction, the movie succeeds in indoctrinating Reagan’s political propaganda.

What’s more, the implications go beyond America’s borders, creating an ideological conflict of international proportions— but with America, of course, as its heroic centre. During the 1980s, Japan and America were in contest for technological superiority, and it was obvious as to which country was emerging as the dominant force. This was a time in which the American public felt alienated by the imported commodities around them — dissatisfaction that culminated in demonstrative destruction of Japanese cars. The movie overturns this dynamic; it provides the average american with an illusory resolution that appeases fear of their country’s growing global impotence against Japan’s booming economy. The teenagers, symbolic of Reagan’s America and therefore vessels of an ideology along the lines of “Let’s Make America Great Again”, operate in harmony with objects. Meanwhile, the enemy, Mr. Vernon, is obstructed and humiliated by the products around him. An alternate picture is painted: within this constructed conflict, America emerges victorious and the ultimate commander of products. So, through cues that align the viewer’s sympathy with the teenagers’ cause, the movie sentimentalises American patriotism and xenophobic distrust of the foreign — effective even on a present-day audience. The teenagers impress acceptance of Reagan’s politics, as well as illusory American supremacy over the Japanese, on the viewer’s mind.