By RJ Shamberger

The United States promises its people many freedoms and presents itself as the land of opportunity where anything is achievable; however, the United States portrays itself as far greater than it is through constant propaganda. The propaganda is everywhere. In our television advertisements. In our history textbooks. In the words of our politicians. And in all forms of our entertainment. The real United States is not a reflection of the image it portrays, and there are immense problems especially of social mobility and racial injustice. The United States is not perfect, yet the movie industry often misrepresents the hardships and inequality in the country. Many Hollywood films downplay the significance of social mobility and racial inequality issues, and this leads to further problems in the country.

Take the movie The Pursuit of Happyness as an example of the constant propaganda that American entertainment feeds the unknowing public, as it perfectly guides its viewers into believing in the presence of social mobility. The Pursuit of Happyness tells the miraculous rags to riches story of Christopher Gardner Sr. whose net worth compounds over a million times fold within the two-hour movie. The film details perhaps the harshest year possible for anyone as Gardner loses his home and wife and goes to the streets with his young child, Christopher Jr., yet he somehow holds on to his hope, and the American Dream beautifully rewards his efforts with riches through his hard work and perseverance. Within two hours the audience witnesses Gardner seemingly rise from the working-class into the middle-class as he invests his savings in a company that sells bone density scanners in 1980s San Francisco. The investment leads to his eventual financial downfall as the scanners become more of a burden than an asset as Gardner learns that he cannot sell the machines to earn a steady income, but he remains under contract as a salesman. Eventually fed up with his inability to provide, his wife who financially supports the family chooses to leave Gardner and his son behind for New York. Without her, Gardner finds himself homeless and caring for his son, all while engaging in a competitive internship at Dean Witter Reynold’s stock brokerage.

The film carefully detracts from Gardner’s actions to continually remind the viewers of the magical promises that the American Dream promises. The film’s opening image is a glimpse of the Declaration of Independence, and the title pays homage to the “life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness” quotation. Further resembling a perfect piece of propaganda, the movie neglects telling its audience that Gardner’s actions are miraculous as it never addresses the social injustices he faces or reasons to his severe poverty. Through consistently conveying the idea of social mobility being a direct result of hard work, the film avoids challenging the words of the Founding Fathers or the reason behind Thomas Jefferson’s specific wording as the title suggest.

Below is the opening scene (beginning at 0:20). Through proper sequencing, the scene tells the audience everything they need to know in the film as it first shows the Declaration of Independence then Gardner and his son. Through analyzing the images, the film outright tells the audience that the plot will be about the United States and its greatness first – evidence of its most important document – then about Gardner’s story.

Instead of dealing with the apparent inconsistencies and conflicts in the United States, The Pursuit of Happyness carefully dances around the problems modern society presses on its main characters. The film completely neglects to acknowledge that Gardner is indeed a black man in the United States during the Ronald Reagan era. There is no instance in which the film addresses Gardner’s blackness, and no one ever refers to him as poor or struggling. In fact, I believe the film scoffs at his poverty in various moments. One scene, in particular, shows an office executive badgering Gardner for cab fare when he exiting the office building. Gardner checks his wallet only to find around eight dollars to which he then gives five of to the executive. In a way, the film says to Gardner “hey, we get it you’re poor, but that doesn’t matter.” Knowing Gardner cannot afford to lose any more money, the film detracts from his reality by forcing him into a moment where his poverty does not matter and instead he must please the executive. In a different scenario, Gardner does not lend the man any money in a more thoughtful decision since he legitimately cannot afford to lose any more money. In fact, this exact situation happens a second time in the film as Chris rides in a cab along with another office executive who then does not pay his fare leaving Gardner with the burden. Obviously unable to afford the fare, the film embarks on a comical section as Gardner must run away from the cabbie and loud profanity aids the moment. Throwing Gardner into near identical scenarios then laughing at him shows how the film wants the audience to his poverty – it doesn’t matter.

Also, the audience must acknowledge the film’s time placement – the Ronald Reagan era. Driven by the uprising of the stock exchange especially on Wall Street in the 1980s the United States’ economy steadily grew under President Ronald Reagan; however, there were still flaws in Reagan’s administration such as worsening race relations and the wealth gap between the rich and ordinary Americans which grew significantly. These were two apparent conflicts in the United States during the Reagan era and given the perfect character and platform to address them the film blatantly fails. No matter how the film tries to portray him, Gardner exists in the period in which there are prevalent social mobility and racial injustice issues, yet the film acts as though the problems do not exist. Yes, Gardner thrives under his situation, but there are underlying issues that he faces throughout his struggle.

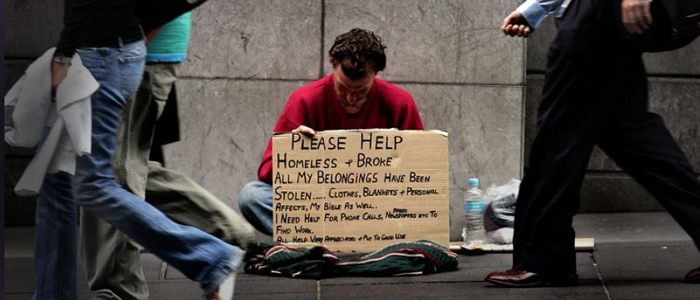

In actuality, The Pursuit of Happyness‘s blatant ignorance to the country’s turmoil during the period is quite utopian. Through refusing to address the issues, the film creates a utopian like the world for the audience to infuse themselves into. In the movie exists a society abundant in social mobility and racial equality, and it uses Gardner’s situation as a platform to prove that the two are present even in perhaps one of the most difficult time periods for such to exist. The film engages its audience into the world that is massively better despite the hardships Gardner experiences. There is no utopia as there can never be complete equality of opportunity and no discrimination amongst people in the real world. So the film presents the issues that Gardner faces. However, it does so inadequately because it includes utopian aspects that do not exist. Even though Gardner miraculously does make it out of poverty, the film does not show the truth of the situation that many people similar to him face on a daily basis and are not as fortunate to make it out of poverty.

More than the film, the entire American movie industry is at fault for selling its audience a utopian world that does not exist – a world that is massively better – and selling it as the reality in the country. The movie industry produces an abundance of propaganda without evident government intervention and through films the country maintains a belief that anything is possible, and that the institutional absence of social mobility or equality for certain groups is a minor problem. Feel good movies like The Pursuit of Happyness are mere pawns in an industry that consistently teaches the audience that the United States is good enough as it is. Throw in a few quotes by the Founding Fathers, taken out of context, and the America the film presents becomes a reality to the audience. By glossing over the negative aspects of the country, the movie industry helps frame the United States as a near utopian society, and that individual can always overcome any of the nation’s problems.

There are repercussions of the movie industry’s actions, and they are dangerous. The person who does not witness struggles similar to Gardner are unable to adequately understand his situation or the barriers he faces before eventually bringing himself out of poverty. Often those very same people who simply do not understand the struggle find themselves in positions of power and their actions or inaction in some cases leads to the recreation of Gardner’s situation for many other people. Maureen Grzan, Rachel Lee, Kevin Pham and Tasha Mamoody support the idea with the following quote from Film as Propaganda in America during WWII: “Movies completely inject into the minds of viewers, with no personal filters or ability for the viewer to think for himself. This leads to a general fear of movies and the ways in which they could control the public’s way of thinking.” The creators of The Pursuit of Happyness do not positively affect the lives of those similar to Gardner because they portray his tale through an incomplete lens. Thus films give propaganda detailing the lack of crucial issues in the United States a route to spread to those unknowing individuals. The film and many others like it continue to misrepresent the situation of black people and those in poverty in the United States and do not provide outsiders with a proper understanding of their status.

Although the movie industry may not directly cause social mobility and racial inequality problems in the United States, it does play a significant role in moving towards a solution which it has not. Instead, the movie industry creates even more issues that reach the greater community of those who are unaware of the struggles of particular people in the country and cause them to neglect the issues just as the industry does. Through consistently misrepresenting the stories that it tells, films present more danger to the United States than most realize and the audience must become aware of the propaganda the films present.

Bibliography

“The Pursuit of Happyness.” Directed by Gabriele Muccino. Produced by Todd Black, Jason Blumenthal, Steve Tisch, James Lassiter, and Will Smith. By Steve Conrad. Performed by Will Smith. Accessed November 24, 2016.

“Film as Propaganda in America during WWII.” History of Information. Accessed November 24, 2016. http://blogs.ischool.berkeley.edu/i103su09/structure-projects-assignments/research-project/projects-and-presentations/film-as-propaganda-in-america-during-wwii/

Vidal, David. “Propaganda in War Reporting on the U.S. War in Iraq.” Stanford. Accessed November 24, 2016. https://web.stanford.edu/class/e297a/War%20Reporting%20on%20the%20U.S.%20War%20in%20Iraq.htm