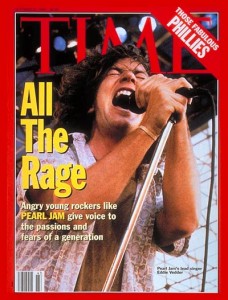

In October of 1993, two years after the release of their debut album, Ten, Eddie Vedder appeared on the cover of Time Magazine, screaming into a microphone with the caption “Angry young rockers like Pearl Jam give voice to the passions and fears of a generation.” Like George W. Bush saying that he listens to Kanye or Hillary Clinton wearing Adidas Superstar’s, Time’s cover was the voice of mothers everywhere asking about “that Eddie Vedder” and why he was so angry. Your parent finally knew why you were wearing flannel, Kurt Cobain scoffed, and Eddie declined comment, fearing the article was “the nail in the coffin” for the rock band who’s first two albums had already reached Billboard’s Top 10. It’s like giving a Nobel Prize to Bob Dylan— he never asked for this. You’re ruining his street cred, Mom.

When I brought up the idea of this essay in the context of grunge music, a friend of mine wondered if grunge was even rebellious and not just “a lot of angst and whining”. She then suggested I talk about the Sex Pistols or the Clash, real punk rock and mosh pits and combat boots and the implicated violence that followed. And she had a point. Sid Vicious might be our model for rebellion, especially considering the BBC kept God Save the Queen off of FM for as long as legally possible. But to dismiss grunge as angst rather than rebellion is both an inadequate depiction of the grunge movement itself and a disservice to the meaning of rebellion, as if to rebel must be insidiously violent or threatening—as if the act of angst and anger and suffering of grunge were not itself an act of rebellion. Grunge might not have the hair spikes or the safety pins, but its emergence during a time when heavy metal and synth music rained, and its crusade for authenticity and “realness” after weathering Reagan’s Morning in America, sets up grunge and the Seattle sound to be one of pop culture’s finest rebellions. This works itself out in a number of ways, some more obvious than others.

The most obvious is the very attitude of grunge, encapsulated in an “I don’t care” sneer that’s just as damning as the “fuck you” smirk of punk. The music itself, loud, aggressive, all garage-rock and sludge guitar and (conventionally) lacking melody, is a rejection of grunge’s predecessors. The style is almost just as important. In a time when Bowie is wearing elaborate costumes and assuming alternate identities and hair bands are all the rage, grunge bands promote their authenticity in their clothes. Flannel shirts, thrift shop shoes, band t shirts and the same jeans you wore to work that day—all culminating in oft unwashed hair. They don’t care what they’re supposed to be. They don’t care about presentation. They don’t care about your rules of hygiene. Much of what made grunge a rebellious movement was the context in which it blossomed. Cobain and Cornell and Mark Arm didn’t want to be Axl Rose, they didn’t even want to be Andy Wood. They rejected the theatrics, the performance, the costume and adornment. Grunge revolved around authenticity, and during the early 90s, authenticity was itself a rebellion.

It’s deeper than that too, though. In many ways, the authenticity of grunge produced a vulnerability and, in particular, a male vulnerability that had never been heard in rock. Beneath the “I don’t care” attitude and head thrashing beats are lyrics and frontmen from broken homes and unhappy childhoods. Vedder laments the lies and loss of his father in singles “Alive” and “Release”, the perverse lyrics of Nirvana’s “Rape Me” are more unsettling than they are either sexual or violent, and Temple of the Dog’s hit single in response to Andy Wood’s overdose and subsequent death describes the guilt of living, saying “I don’t mind stealing bread/ from the mouth of decadence/ But I can’t feed on the powerless/ when my cup’s already over-filled”. This is a male fragility that’s hardly displayed in society, front and center in grunge’s biggest acts. Joe Levy of Rolling Stone describes it in a Pearl Jam documentary saying: “Never before and never since, really, had men so successfully talked about the problems of, well, being men… In rock and roll that doesn’t usually happen.” Suddenly, the performance of masculinity that took form in the lyrics of everyone from Bon Jovi to Metallica was discredited. The sexual prowess of the hair bands and the violence of heavy metal was no longer axiomatic with being a man. Grunge rebelled from the conventional forms of masculinity and permitted men to feel, deeply, too, in a way that rock and roll had never before seen.

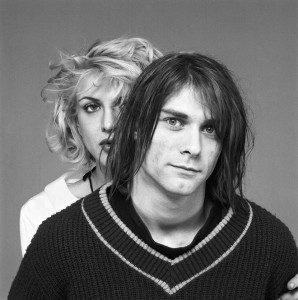

More than that, grunge went so far as to subvert traditional gender norms and to advance the feminist perspective, if only marginally. That Pearl Jam’s “Daughter” is written in the perspective of woman, and that it’s rejecting both the title and role of “daughter” given to her by an evidently oppressive father is not insignificant. Furthermore, cultural theorist Karen Aubrey credits the grunge movement with a certain amount of “gender-bending” in her essay Body Piercing: Gender Nihilism in the 90s. She describes the androgynous quality of grunge’s so-called uniform, claiming that the look is “based on the indistinguishable covering of those areas of the body which identify us as male or female… Standards of conventional sexual attractiveness, which encourage emphasis of gender designating body parts, are thereby not just ignored, but defied.” So we get Kurt Cobain and Courtney Love sharing a wardrobe and, if they’re both wearing glasses, we don’t know which is which. The flannels and baggy t-shirts are more than just the designated slacker uniform, in fact they’re a rebellion against the hetero and cisnormativity that characterizes the very world they’re railing against. Grunge is a formal de-sexualization of the body. Obscuring the of body shape, the gender bending of Kurt’s feather boas, but also the unwashed hair, Eddie Vedder launching himself from stage scaffolding into the crowd, and the utter lack of sexual content in most grunge songs all refute the body as a sexual object. In the same way that grunge rejects traditional masculinity, it also rejects the sex-god status of it’s predecessors. My body is not yours to sell, they might as well be screaming.

And then of course there’s Pearl Jam boycotting Ticketmaster and taking them to court, Pearl Jam refusing to do music videos and then, for a time, refusing to give interviews, Kurt Cobain dismissing MTV Video Music awards, Kurt Cobain dismissing Grammy nominations, Kurt Cobain attempting to reinforce his authenticity by calling Eddie Vedder “careerist”. All of this amounts to John Lennon asserting that the Beatles are bigger than Jesus, just multiplied by a few frontmen and repeated continuously for five or six years.

–

But nothing gold can stay.

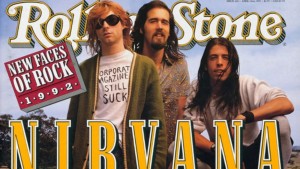

In 1992 Nirvana appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone, Dave Grohl long-haired and gangly, Kris Novoselic bearded and good-natured, and Kurt Cobain wearing a t-shirt that reads “corporate magazines still suck”. By then, Nevermind, the band’s second record and first produced on a major label, was already certified gold and had replaced Michael Jackson as number one on the Billboard charts. It didn’t matter if corporate magazines still sucked, because Kurt would continue his rise to Gen-X messiah even after criticizing Pearl Jam’s Time cover, withdrawing from the public, cancelling tour dates, and eventually killing himself. NAFTA had been signed, Wall Street was deregulated, and the market was in control, even of the very thing that claimed to rage against it.

Carl Swanson characterizes the capitalisms co-opting of grunge in an article for New York Magazine, linking the commodification of rebellion with the rise of Bill Clinton and neoliberalism and ultimately asserting that “niche markets were becoming mainstream propositions—and soon gave us the entire gloriously fractured culture we’re unavoidably (and more often than not wirelessly) connected to today.” Atlantic Records bought an indie label, Marc Jacobs came out with a grunge line, and somehow Pulp Fiction was popular in the mainstream. Consumer culture had caught on with rebellion and began reproducing it tenfold.

Grunge’s authenticity is over almost before it begins. In Milan, the Perry Ellis collection that Marc Jacobs debuted for his 1993 spring show featured models in thousand dollar dresses, adorned with wool caps, unlaced doc martens, and “flannel” shirts tied around their barely-their waists (the “flannel” was actually silk and Jacobs claimed there wasn’t a single thread of polyester in the collection). Soon, grunge fashion appeared in department stores like Macy’s, only ten times the price of the thrift store jeans Novoselic is wearing on tour. Later that year, when Vedder would appear on the cover of Time, he denounced the idea of success that came along with it, claiming that it “could destroy everything. It can destroy what’s real…which is your life. It can make it a commodity.” In his suicide note, Cobain languishes for the lack of passion he feels for music, feeling as though he “should have a punch-in time clock before [he] walk[s] out on stage.” What was once an expression of anger and disgust and poetry is now an hourly wage job. What was once a revolt against the man has now been structured by the man. It’s no coincidence that you can buy t-shirts with Cobain’s hand-written suicide note across the chest. Peace, love, empathy, capitalism, right?

The music industry itself seemed to cannibalize grunge, too, not only exploiting and over-playing the already existing grunge bands, but searching everywhere for mildly angsty threesomes that they could dub “the next Nirvana”. Like The Monkees after The Beatles, bands that hailed from far outside of the Pacific Northwest were anointed “grunge” while Mudhoney and the Melvins remained fairly stuck in Seattle. Pearl Jam was recording with Epic Records, Nirvana left founding grunge label SubPop for Geffen, and Alice in Chains was with music conglomerate Columbia Records. Bands like Stone Temple Pilots, who were based in the corporate world of San Diego, were marketed as grunge band of the Pacific Northwest despite being an evolving alt-rock and glam-rock band. STP sold 40 million copies of their debut album Core while British band, Bush, and Australian band, Silverchair, found a seat on the bandwagon, each respectively considered one of the best grunge bands of all time. So much for Seattle.

In a genre that was founded on authenticity, and whose authenticity was rebellious in its very nature, the culture and music industries capitalized on the aesthetic of grunge while destroying its very basis. Without the angst and tortured introversion of Kurt and Eddie, without their humble upbringings and conscious efforts to subvert what was normal, what was dubbed the “Grunge Movement” became nothing more significant than greasy hair and a new way of dressing. The culture industry figured out how to co-opt the signifiers of youth rebellion and sell them as the real thing, voiding grunge of its vitality and filling consumers with pretensions of counter-culture. Fashion and guitar cords and attitudes are easy to adopt and milk for all they’re worth—it’s the authenticity that was left at the wayside.

“Everybody loves us/ Everybody loves our town/ That’s why I’m thinking lately/ The time for leaving is now” – Overblown, Mudhoney

It’s three days into writing this paper by now and I’ve revisited all of my favorite documentaries and dug up old articles that repeat the same information, the same bits of the few MTV interviews that Pearl Jam and Nirvana actually did, the same grand message—these are tortured souls, thrust into a spotlight they never wanted, coming to terms with what it means to be authentic, what it means to be an artist, what it means to be a voice of a generation. I keep coming back to the moment during Pearl Jam’s 1994 performance on SNL, only days after Cobain’s suicide, where Eddie Vedder touches the “K” that was sharpied onto his shirt and ends their song Daughter with a whisper of Neil Young; “My my/ hey hey/ rock and roll will never die/ there’s more to the picture than meets the eye.” Cobain’s suicide letter (still available for purchase) famously quotes the line “it’s better to burn out than to fade away” of the very same song, shifting the unbearable burden of speaking for an entire generation to the shoulders of Young. Perhaps for Cobain the weight was finally lifted.

At the time of his death, Cobain’s estimated net-worth hovered somewhere around $100 million and, by 2015, had reached $450 million as Nirvana singles continued to sell and be streamed online. Forever 21 sells t-shirts to teenage girls with Nirvana’s cross-eyed smiley face on the front while Timberland and Doc Marten stocks have continued to rise since the grunge era and Pearl Jam never did take down Ticketmaster. Along with the grotesque sums of wealth amassed with grunge’s commodification came the myriad of critical reviews (not unlike my own) that call Cobain and Vedder and the whole movement a sham for being so undefinable. Grunge, outside of the definition that corporate America has given it, is remarkably difficult to pin down, particularly in terms of sound. Nirvana is not Pearl Jam is not Alice in Chains is not Tad is not Mudhoney—often they don’t even sound alike. What’s lost in all the theory and analytics and claims for authenticity is the very real, very tangible, human toll. Cobain is dead, Vedder was close, Pearl Jam is the only band from that era still playing, and grunge has become a cultural phenomenon and Kurt Cobain a token phrase, disassociated from the very real man, the very real sufferer that he was. The effect of the commodification of grunge, of any counter-culture movement, is the dehumanization of the subject and an exercise in making protest, art, poetry, and expression desperately futile. We, the consumers, are estranged from the very people we believe to be our very own individualized prophets, and they, are rendered martyrs for a cause they set out to defy.