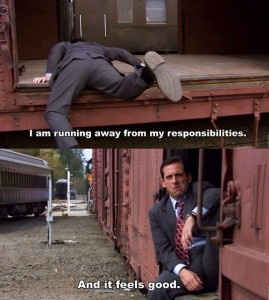

Last night I watched The Office instead of doing homework. I missed my boyfriend, who I haven’t seen in almost two months, I missed my dad, who is dead, and I felt exceedingly average after having been told by a professor “not to try to sound too smart, anymore” in one of his comments. So I watched the one where Michael goes broke, or, more accurately, the one where Jan (former boss of Michael, current manipulative lover) maxes out Michael’s credit cards buying carpet and Micael tries to declare bankruptcy (by declaring the word “bankruptcy”), eventually fleeing to a stationary boxcar like a vagabond, “running away from [his] responsibilities.”

Jan finds him and brings him back to the office. They break up within the next few episodes and Michael never takes off financially, as far as I know. By the end of it, I forgot about the work I was supposed to do and went to bed well before eleven o’clock.

It seems unnecessary to introduce The Office. Anyone with access to the internet, and therefore anyone reading this, has heard of The Office. There is no doubt in my mind. Anyone who watched the 2008 Super Bowl, wherein the wildcard New York Giants decimated the previously undefeated New England Patriots, was greeted with a new episode of The Office, afterwards. The sudden popularity of “that’s what she said” jokes in the mid to late aughts—this was at the hand of Michael Scott. Still, for the sake of comprehensiveness, it’s important to note that The Office is not a typical Seinfeld/Friends-style sitcom from NBC, but rather documentary style show that details the banality of everyday life working in an office for a paper company. The walls are beige, the computers are bulky, the desks are ones you might find in a college dorm room. The Office is unglamorous, mundane, and is a comedy of characters rather than circumstance. This is why people love it.

In the realm of production and structure and critical analysis, there are a number of reasons to like The Office. The writing, for at least the first five seasons, is genuinely funny and creative. The one shot filming without any laugh track makes the humor almost deadpan, while the interviews that are interspersed within the plot are famous for their confessional humor. Characters feel whole and not like schticks or archetypes, and the very plot of each episode feels like a pop culturally relevant comedy of errors. There is a reason that The Office is so critically acclaimed, winning an Emmy for Outstanding Comedy Series only a year after it had been on air. With the original cast and writing ensemble, The Office is a technically good show, with clever writing, full characters, and intelligent filming. But technical skill only gets a TV show so far, and Emmys and Golden Globes aren’t voted on by the people. So what makes a show like The Office so beloved? And what does it say about the general population that a show like The Office can become so deeply ingrained in the hearts of the people?

The magic of a show like The Office lies in its ability to mirror real life. The Office takes the conventions of reality TV and flips them, where with reality TV everyone knows it’s supposed to be real but is actually fake, consumers can watch The Office, knowing that it’s fiction but feeling as though there is some deeper, resonating reality to it. There’s a safety in fiction that The Office capitalizes on, and a magic in the mundane that makes it so compelling.

For one thing, The Office is set in Scranton, Pennsylvania— a place that, nowadays, few people have been to but most people recognize. The ambiguous familiarity that viewers feel towards Scranton is half the battle. Unlike New York, Boston, or LA, all of which are too extraordinary and well known to resonate with viewers, Scranton provides a familiar basis while allowing viewers to fill in the details. Scranton can be the place where city where they grew up, the place their grandparents moved from to start a better life, or the town outside of the college they went to. Either way, viewers recognize Scranton within the realm of their own life. The workplace, then, only makes this familiarity tenfold, appealing to the middle class worker everyone in America presumes that they are. Aesthetically, everything about The Office is unremarkable and commonplace in a way that makes it accessible to even the teenagers watching who’ve never stepped foot in a workplace. Like florescent lights and white tile are enough to tell the viewer “hospital”, like car horns, windchill, and cloudy skies are telltale for New York, The Office and Scranton are conventional signifiers of middle class America, desk jobs, and unfulfilled dreams.

The other half of it, then, is the people. Like Scranton is your uncle’s hometown, Jim is your best friend, Michael is you incompetent boss, Angela is the holier-than-thou know-it-all who sat next to you in high school and Phyllis is your great aunt you see every five years. These are people you know, people you work with, people you went to school with—this is us, collective.

So the real sucker punch of The Office is that it tells middle class America’s story back to middle class America, only with more office antics and more that’s what she said jokes than average. Now the question remains— what does this say about us, as a people?

As with most things, there are a few ways of looking at it.

Part of me, and I think part of all of us, wants to say that our love for The Office, for any workplace comedy or drama, is comforting. It’s like going to the same house for Thanksgiving every year, it’s like hearing the song your dad used to sing while making coffee—The Office is our everyday lives, packaged into something funnier, more hopeful, and just as complicated. We watch Jim work a job that is below his intelligence level, that is unsatisfying and banal, but we also watch him fall in love, get the girl, and start a family of his own. He transcends his career level unhappiness to find true, familial and romantic happiness. It’s not overly romantic nor is it the consuming plot of each episode, but it is always there, and it’s always hopeful. The same could be said for Michael and Holly, or for Dwight and Angela, only in more complicated and less conventionally romantic ways. The other part of it is that despite financial, romantic, and emotional crises, The Office is a generally happy show, with generally happy characters who are not all that put out by the average conditions of their existence. We watch Jim leave brokenhearted for Stamford, Pam’s failed engagement, branch mergers, the sale of Dunder Mifflin, the heartbreak of Dwight, the strain between Jim and Pam, and relative financial instability of both the company and all of its employees—and, still, The Office is a comedy. The happiness of it is a hopefulness for every viewer, watching their own lives unfold on screen and being told that they, too can be happy. We, too, can find the love of our life at a desk job. We, too.

But there is another side to it. There’s a placation, an acquiescence, a platitude in The Office that, sure, comforts us but, at the same time, makes us stagnant, quiet, and appeased. Pam, a receptionist, wants to be an artist. When she shows her work at a local gallery, Michael is the only one to show up, while Oscar and his boyfriend muse from afar that her work is “unimaginative” and “motel art”. Later in the series, Pam quits a Pratt School of Design summer program and becomes a paper salesman, and then the office manager. Jim always wanted to be a Philly sports writer. Instead, he works as paper salesman, for a short time becomes a branch manager, and then creates his own sports management company—which he eventually abandons to co-founder Darryl in order to keep his family together. Michael never gets promoted beyond manager. Dwight waits eight years to become manager and, even then, he’s only truly happy when he finally marries Angela in the series’ final episode. And somehow this is still a comedy. Still, we find it funny. Still, we are convinced, they are happy. The truth is that watching The Office is more than just comforting and entertaining—it’s reassurance that we’re not wasted potential, that we’re not nobodies, that we’re not cogs in the American business machine. Every art school dropout, failed dreamer, average joe with above average imagination is tole “it’s okay, you are not alone, and you will be okay.” In watching The Office, we are given an inside look at the banality of everyday office workers, shown their intimacies and their idiosyncrasies, and told that we, too are special. We, too, can be satisfied in an unsatisfying circumstance. The comfort derived from The Office is more than simple recognition of a life like our own, but rather a twisted reassurance that the circumstances of middle class America are not all that unsatisfying, because if Jim and Pam are happy then who’s to say you and you’re husband can’t be?

What The Office tells us is to be happy with the little things, because the big things aren’t changing any time soon. And while this might seem like sound, motherly advice, it also ends up placating the legitimate, constructive grievances one might have with their situation. It’s valid to dislike your job, to find it unsatisfying, to lose patience with an incompetent superior. And while there is nothing innately wrong with working a desk job (it is, in fact, a first world luxury that can only be complained about in such a context), it’s still legitimate to feel frustrated, to be unhappy—and it is important to act on those feelings. To want something better, more stimulating, more fulfilling, is not wrong. To quit is not wrong. Middle and working class America have a list of grievances a thousand pages long and, in a larger, cultural sense, The Office works to appease those grievances, but never fix them. In the opposite way in which shows like American Idol or The Voice tell people “this could be you”, The Office delivers the message “this is you, now laugh along” to the same viewers. Work, in The Office, becomes each character’s whole life. Family, friends, love—none of these are independent of the workplace. And while that’s obviously a function of the fact that its set in an office and literally titled “The Office”, it also presents a reality where work is the main function of people’s lives, the common ground of relationships, and the only source of stimuli. While this is inevitable and true for most all working class Americans, it doesn’t mean it has to be desirable in the way that Dunder Mifflin and The Office make it seem.

After watching The Office the other night, I woke up the next morning having not read Paradise Lost for my 8:30 English class. My boyfriend is still three hours away, my dad is still dead, and I still don’t know what my professor wants me to do with my writing if he doesn’t want me to “try to sound too smart.” I didn’t accomplish anything other than a good night’s sleep. Nothing was done, the circumstances of my life or my work habits hadn’t changed, the world in Williamstown and I, too, remained the same— it was fine, comforting, even. I got out of bed, brushed my teeth, and got to class by 8:25.