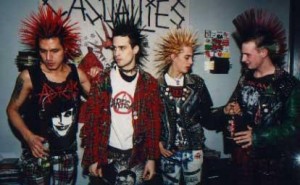

“Because you’re young, you’re angry, you can break a bone and you just don’t care. If you like punk rock, kids that are angry, primal stuff, backyards are like the place to do it. Nobody’s going to tell you what to do. They’re going to applaud you” (Cuevas). From the outside, punk represents a certain aesthetic: Angsty yet apathetic teens in unkempt clothing sporting multiple piercings and worn-down spiked leather jackets. This one-sided view, and lack of understanding of its origins thereof, have spurred a general aversion to the seemingly dark, haunting group, and fueled an antagonistic attitude that has led to a rise in school bullying incidents and public scorn/disapproval. This omnipresent attitude directed towards punk culture, coupled with society’s perception of them as ‘other’, serve to justify the ostracization of the social group. This isolation is a defining characteristic of what it means to be considered a subculture: a community that subverts mainstream norms by creating a safe environment for what is usually a particular type of deviant self-expression.

Examples of punks

The punk subculture can be dated all the way back to the 1970’s, when it emerged from musical, philosophical, and political movements in the United Kingdom, Australia, and United States. Original participants embarked on a quest for independence from the culture industry, which controlled rock and roll in the 70’s. As part of its individualist doctrine, the punk lifestyle aims to renounce hypercommercialism and the prevailing media culture, which are known to be suggestive of mass behavior and standards for the norm (Moore). Punk culture thus counters mass consumption, and promotes one’s personal agency. Supplementing these notions, the punk ideology follows a ‘do-it-yourself ethic’, which in part encourages an insistent avoidance of major corporations and media outlets. The scene’s original product distribution consequently earned the admiration of thousands of teens and young adults who valued unrestricted means to “create [their] own identity and be in a network of like-minded individuals” (Moran).

Furthermore, since procuring punk music involves little to no money at all, the community appeals to those who come from low income backgrounds. Punk music is the epitome of subculture, spreading its ideas and messages through its own form of art that is almost always produced with minimal effort – a DIY approach that supports anybody’s ability to contribute (Moran). In fact, the group’s promotion and endorsement of its ideologies depend on the socialization that their original works generate. Thus, music enables the subculture to distribute media without relying on mass production. This gives the members of the subculture a sense of accomplishment because they can entertain the punk community independently. As a part of this type of production and distribution, many independent punk record labels have been established, ultimately building a social network between punks in which the musicians can travel to various cities and venues to keep the subculture alive on a worldwide scale (Moran). Fanzines, amateur-esque magazines and other “expressions of self philosophy,” are also distributed throughout the punk community to promote the importance of self-expression and individuality. The DIY production of fanzines and music in the punk scene caters to a group of people who do not have an incredible or unique talent or skill to feel included in the subculture; anyone has the capability to do anything, without the prerequisite of any singing, performing or writing expertise – everyone can share their songs in front of other punks or distribute their writing as entries in a fanzine (Moore). As a result, everything produced in the punk subculture is raw, natural, and all-inclusive – a testament to the core punk values of abandoning popular culture, deviating from commercialism, and countering mass media.

Despite punk’s goal of addressing the needs of a certain minority, the reality is that this community is predominantly white. From the start, punk has appealed to middle-class “straight white boys,” who think that they are too good for mainstream rock, yet still feel inclined to express themselves through music (Nomous). Because the punk culture preaches individualism and resistance against the norm, part of this behavior is exercised by punk teens as an additional rebellion against parental authority and to what is usually the white middle-class privileged lifestyle (Nomous). Therefore, the teens that are breaking from both their privilege and parental authority are trying to escape something they are exposed to on a daily basis. These are the kids who, overwhelmed by consumerism and mass production, have the flexibility to break free and seek individualism through controversial norms such as the punk scene (Nomous). Hence, the punk scene proves to emerge from a place of concentrated privilege and financial security, explaining the racial exclusivity of the culture in that white punks have different aspects of life to worry about than punks of color.

Not only is punk culture mostly white, but it also fails to include minority groups or directly address the marginalization they face. Because race is a social construct that creates deep-seated divisions, the punk community makes an effort to disregard race by denying its existence altogether, assuming that everyone, regardless of race, can be a part of the group as equals (Nomous). Despite this attempt to unify everyone by disregarding race, ignoring this significant piece of identity actually makes punk exclusive, in that it assumes everyone has the same experience or background.

Otto Nomous, a punk of color, recalls an experience he had with white punks during the anarchist movement:

I have received quite a few very negative and defensive reactions from white anarchists whenever I would mention the words “white” and “middle class” in the same sentence. Some of them defiantly point out that they’re actually “working class” because they grew up poor or have to work. What they fail to realize is that it doesn’t change the fact that they are able to blend in and benefit from the current anarchist scene which is predominantly middle class, and from white skin privilege (Nomous).

Nomous explains a conflict between the subculture’s ideologies and practices, in particular how the element of race contributes to the homogenized subculture and why this intentionally excludes racial minorities. Although the community aims to be inclusive, they simply cannot cater to issues beyond those within a “white” sphere – unifying all white people across a spectrum of economic backgrounds. Frankly, race begins to unfold into additional problematic layers when analyzed from a socioeconomic perspective, which is why the group simply cannot accommodate to race-related issues in the backdrop of its predominantly white following. While other white members can participate in the unity of the punk scene regardless of socio-economic standing, and have the privilege of commonly being the support and not the ones needing it, a person of color has a completely different identity that they must reconcile to even feel included. There is no mask of uniformity to hide behind in the group (Nomous). The possibility of being subjected to these identity and inclusivity struggles thus exemplifies how the punk scene fails to represent those of other races who may want to join the subculture. In response to this lack of representation, smaller sub-groups that have representation from various different minority groups have emerged. They have also managed to keep in line with a similar “punk” aesthetic and means of communications. Take for example, the punk scene in East Los Angeles – an area teeming with crime and poverty where day-to-day survival is a real concern (Los Punks). In this community, punk has helped teens and young adults to cope with the present hardships of their upbringings in a much more local and radical way than what’s seen in white punk subculture, or recognized by the general public.

Jorge Herrera, born in Guayaquil, Ecuador and lead singer for The Casualties, performing for hundreds of Latino punks.

Corrupted Youth, from East LA, performing in a backyard venue

In predominantly Latino-populated communities such as the one in East LA, music has become a pivotal aspect of the punk subculture. This medium of communication not only creates a safe space for those who refuse to conform to the mainstream, but also enables Latinos to address shared social issues and personal experiences in the community. The documentary Los Punks, takes a closer look at the underground punk music scene, in which dirty backyards are the main attraction for those in the subculture. In the Latino punk scene of East LA, bands travel around the city and perform in backyards for little to no money, with the exception of very small entrance fees. There are many instances in which the money collected during these events have been used to fund a wide range of needs, such as a loved one’s funeral, medical treatment for sick relatives, or charity for of impoverished families in the community.

Los Punks “We are all we have” encapsulates the importance of the subculture in Latino communities

The punk subculture serves as a panacea for “La Tristeza”– a concept that encapsulates the “sadness of living in the hood” (Los Punks). This term was introduced in the documentary by Boyle Heights native and lead singer for Rhythmic Asylum, Gary Alvarez. His involvement in the punk scene was primarily conscious of what consciously-oriented, since he viewed the subculture as a facilitator of radical change. Moreover, the documentary discusses the stories of many who rely on the punk scene for temporary support and community while they hope for future accomplishments or resolutions of ongoing problems. One member of the Boyle Heights scene explains that he plans to attend law school to help fight injustices among disenfranchised groups. Another Latino punk member, Alex, who is the lead singer of a punk band called Psyk Ward, mentions that his participation in the punk subculture gave him a reason to live after several suicide attempts. The Latino punk subculture provides a community for punks of color to learn from each other and discuss social issues–an opportunity that isn’t typically available to them through other institutions. Many white punks quickly criticized people of color for creating such a subgroup–calling it “self-segregation” (Palafox). They use the scene’s DIY ethic to address all type of concerns and thus enable those in the scene to interconnect, whether it be through music or fanzines. Such a scene does not correlate with the predominately white one, because the struggles of a minority group is something that white people simply cannot relate to (Palafox).

Los Crudos speaking out on the injustices of marginalized people through their songs and performances

Thus, does the racial divide between the Latino and white punk subcultures insinuate that the Latino punk scene is in and of itself a separate subculture altogether? From its definition, a subculture promotes rebelling against the mainstream, but do so as a predominantly white group. Aside from punk, predominantly white subcultures such as emo, goth, and hipster feed off the minority culture, via their music, clothes, etc. and use it to create a community that solely revolves around their problems –as white people appropriating unfamiliar ideas and lifestyles considered deviant from the norm (the norm being inherently white as well). Hence, such subcultures are exclusively white and uniform in their ideologies and beliefs. Latino punk thus has only one thing in common with its predominantly white counterpart– and that is rejecting mainstream media. Except in their case the mainstream is the homogenous white punk scene of the media and history. Their use of the very basic punk aesthetic and founding ethic – to promote a different function of the community – challenges their being simply subculture, because they’re not white. Therefore, against the backdrop of the white punk subculture, the Latino punk scene ultimately proves to be a “subculture within a subculture” (Palafox).

Works Cited

Moore, Ryan. “Postmodernism and punk subculture: Cultures of authenticity and

deconstruction.” The Communication Review 7.3 (2004): 305-327.

Cuevas, Steven. “Documentary Reveals L.A.’s Secretive Backyard Latino Punk Scene.” KQED

News. N.p., 10 June 2016. Web. 21 Nov. 2016.

Moran, Ian P. “Punk: The do-it-yourself subculture.” Social Sciences Journal 10.1 (2011): 13.

Brinkhurst-Cuff, Charlie. “Why Is the History of Punk Music so White?” Dazed.

DazedDigital.com, 12 Nov. 2015. Web. 19 Nov. 2016.

Nomous, Otto. “Home – Colours of Resistance Archive.” Colours of Resistance Archive. N.p.,

n.d. Web. 22 Nov. 2016.

Los Punks. Dir. Angela Boatright. 2016. Film.

Palafox, Jose. “Screaming Our Thoughts: Latinos and Punk Rock.” Alternet. N.p., n.d. Web.

22 Nov. 2016.