Azar Dixit

The title of a popular Onion article, “Two Hipsters Angrily Call Each Other ‘Hipster‘”, quite humorously and simply highlights an interesting curiosity about hipster subculture: there seems to be a pretty good understanding of what it means to be “hipster,” yet no one group of people accepts this label as their own. Hipster subculture is unique in inspiring universal discomfort in a way that few other subcultures or trends of today can even come close to; the modern conception of the average hipster is convinced of his pretentiousness and annoyingness to the point that even those who subscribe to the understood beliefs, styles, and actions of this subculture consider the label an insult to their authenticity (Greif 1). Mark Greif, New York Times writer, attributes this response to the fact that the label “calls everyone’s bluff” in terms of authenticity and taste. This assertion seems to largely fall short of an entire explanation; the sweeping discomfort brought about by the development of the modern hipster runs much deeper and echoes societal tensions to a degree that a simple distinction between genuine and unoriginal fails to embody.

Examples of hipster style, specific to Portland, Oregon

The hipster subculture is primarily composed of affluent millennials who tend to be college educated and politically liberal, live in gentrified neighborhoods, associate with indie/alternative rock music, and dress in styles that subvert mainstream fashion. The crux of hipster ideology is to portray an entirely unique state of being and nonconformity through personal taste, often through choice of music, fashion, and alternative lifestyles (Grief 2). As one of the most prominent new subcultures of the elite, hipsterdom is known for recycling past trends and styles of historically ostracized and oppressed groups, as is seen in the resurfacing of trucker hats and wifebeaters, both of which were previously typical styles of working-class, white Americans. The word “hipster” itself has a history that reflects this pattern – the term was first used to describe black subcultural jazz artists in the 1940s, and eventually extended to include those artists’ white fans, who embraced the realm of new, exciting, and exotic energy that they admired in their favorite black artists. Hipsters in these decades, both black and white, were convinced of the powerlessness of minorities to make choices about their own lives and insisted upon the importance of personal knowledge gained before being influenced by what society teaches (Wailer). The term resurfaced in 1999, again likened to the value of knowledge gained before societal influence, now tied to “discovering” fashion and lifestyle trends before the mainstream (Grief 2). The fact that elite culture determines its stylistic preferences in light of both current and historical subcultures of common people is an interesting change. It puts the hipster in an unfamiliar realm – directly in between the recycled aesthetics of other, rebel subcultures and the underlying elite privilege of the dominant culture.

In his essay, Grief begins to decipher the cultural phenomenon of the hipster by defining taste as the central drive in its appropriation of marginalized cultures, and as their own brand of a seemingly paradoxical elitism. French philosopher Pierre Bourdieu claims that the notion of the elite possessing a superior taste can be explained by the elite’s usage of it ‒ as an affirmation for their right to power and privilege ‒ to oppress the lower class and maintain societal divides. Bourdieu found that taste can accurately be predicted by socioeconomic factors (specifically one’s class at birth and achieved education level), making it predominantly a reflection of environmental factors rather than a representation of individual expression or assertion. Moreover, Bourdieu observed that a sizeable portion of highly-educated French elites showed a marked preference for flea markets ‒ a finding largely reminiscent of the “thrifting” trend brought into the contemporary mainstream by hipster subculture(Bordieu). Bourdieu’s argument would suggest that the hipster notion of cultural supremacy stems solely from economic motives, but this assertion contradicts the quintessential “hipster” as antipodal to those with mainstream tastes and lifestyles, invariable to equivalent social class. Even though the hipster subculture distinguishes itself from others by taste, and therefore has inklings of classism through the implication of superiority over those with lesser taste, it furthers its distinction by separating itself from those in the same class who do conform to the mainstream through intellectual superiority. This doesn’t mean that the “hipster” is a cultural figure that is free of elements that suggest the inferiority of the poor (e.g. few working class people actually have the time and money to maintain the exacting form of authenticity that is tied into being hipster), but rather that its underlying assumptions are, as Bourdieu describes, more a product of the hipster’s place in society than any sort of idea or image specific to the subculture itself. The rejection of those of an equal social class on the basis that they embody the mainstream is a feature of hipsterdom that has been noted by the television show, Portlandia. In a 2011 skit, the show featured a disgruntled hipster who furiously proclaims “It’s over!” after witnessing a clean-cut, white collar man enjoying the same activities and interests as him. The hipster continuously renounces the reflected aspects of himself until he has completely taken on the other man’s original appearance and behavior. What’s interesting about this skit is that it wouldn’t really work if Portlandia’s writers had casted a black man to play the hipster’s counterpart, since “the professional white man” is the mainstream that the hipster avidly avoids.

The disgruntled hipster writes “IT’S OVER” on a window to the confusion of the white-collar man sitting in a cafe.

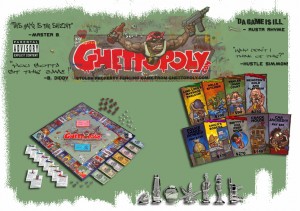

The hipster’s perception of the lower class innately possessing a lesser taste brings up the question of how race is perceived in the context of this intellectual elitism. In being a supposedly counter-cultural and decidedly liberal subculture, the modern hipster outwardly embraces ideals of racial harmony and progressive reform for marginalized groups. However, the commercialization of hipster culture in recent years has led to controversy over the style’s tendency to appropriate the cultural figures/practices of ethnic minorities, without attempts to credit their origins or appreciate their cultural sanctity. The subculture’s persistent growth has thus begun a trend of increasing rates of cultural appropriation, or at least increasing its publicity. This is particularly so in the fashion of music industries, as concert-goers and performers alike are now more commonly wearing bindis, traditional headdresses, and other culturally significant garb during concerts and music festivals (e.g. Coachella, Burning Man, Lalapalooza, etc.). Although the current version of mainstream cultural appropriation may be new in some ways, it nonetheless derives from a combination of intellectual elitism and liberal political leanings, that together have created an ironic refusal of political correctness amongst its proponents. This tendency has led to the phenomenon coined “hipster racism,” which occurs when racial stereotypes are used ironically under the pretense of a person’s self-perception that he/she is not actually being derogatory (Quart). This can be explained by noting that the higher standing hipsters feel they have over others may have easily evolved into a penchant to diverge from social norms as well as established guidelines of political correctness. There is present a fundamental belief that they have progressed so far from common bigotry that they are permitted to make remarks that would normally even be considered racist, when coming from others less forward-thinking than them. The principal problem with this guise is that the comments are most often representative of discriminatory motifs – the humor in jokes is not always clearly ascribed to any ironies or understanding of minority sufferings. One of the most infamous perpetrators of this kind of disregard for political correctness is the trendy and self-proclaimed “hipster” clothing chain: Urban Outfitters. The company once sold a hugely offensive board game entitled “Ghettopoly,” a knockoff of the classic Monopoly™ board game, that propagated harmful stereotypes about African Americans who live in ghettos. Land properties in the game had titles like “Cheap Trick Avenue” and “Smitty’s XXX Peep Show,” and bonus cards had descriptions such as “You got yo whole neighborhood addicted to crack. Collect $50” (The Week). Only through the false perception of their being above discrimination could this have had success in a store that attracts droves of young liberals. The underlying justification for the production and sale of this inarguably racist product boils down to blatant acceptance of prejudiced sentiments, with the assurance that the buyer is obviously not prejudiced. In this way, the liberalism of Urban Outfitter’s clientele, alongside the store’s trendy image, overpower norms of political correctness, due to the commercialization of the hipster’s modal “ironic” thinking. The end product of hipster racism, as seen through the example of Ghettopoly, is just as damaging as displays of prejudicial sentiments by poor, right-wing Americans that the consumers of Urban Outfitters would normally be quick to fervently condemn.

Image of cover of the board game “Ghettopoly” carried by Urban Outfitters

The hipster as a modern symbol is not much more than a quirky makeover of problems that have challenged American society for years. It is a refined representation of the oppression and “bad taste” of the poor that has allowed elitism to hold hands with progressivism. It is a response from elites that embodies styles of the common people’s subcultures and cherry-picks trends without respect for their sanctity or meaning. They trivialize issues such as race in a way that puts those at the top of society in a position to liberate themselves from political correctness and justify their prejudicial actions. It is heavily implicated that this justification can only occur amongst the intellectually “superior”, while the intellectually “inferior” are labeled backwards bigots for expressing the same ideas. This dichotomy of racist versus accepting or backwards versus progressive is obviously likely to result in broad generalizations that work to either support that elites are so removed from bigotry that they’re entitled to tell offensive jokes while not being part of the problem, and that less educated people displaying similar sentiments are racists or sexists who represent all that is wrong in society. Thus, the strong and largely unanimous discomfort brought about by the initially subcultural figure of the hipster is not just the product of it questioning everyone’s sense of taste, but also of the consequential classist and racist undertones that exist within the concept of taste itself. And if you’re still not exactly convinced of the extremely political existence that hipsters possess, you should check out the German Neo-Nazi party’s recent adoption of hipster style – combining the trendiest hipster fashion and lifestyle with classic Neo-Nazi ideals, the group also differs from American hipsterdom in that it readily accepts the title of “Nipster” (Smith).

Advertisement for a Nipster T-shirt line

Works Cited

Bordieu, Pierre. “A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste.” (1984): 9-169. Monoskop.org. Harvard University Press. Web. 17 Nov. 2016.

Greif, Mark. “The Sociology of the Hipster.” New York Times. New York Times Company, 12

Nov. 2010. Web. 17 Oct. 2016.

Greif, Mark. “What Was the Hipster?” NYMag.com. New York Times, 24 Oct. 2011. Web. 17 Nov. 2016.

Quart, Alissa. “The Age of Hipster Sexism.” The Cut. New York Media, 30 Oct. 2012. Web. 17 Nov. 2016.

Smith, Kyle. “10 Alarming, Hilarious Facts about Nazi Hipsters.” New York Post. NYP

Holdings, 14 Aug. 2014. Web. 17 Nov. 2016.

The Week Staff. “15 Urban Outfitters Controversies.” The Week. N.p., 29 Apr. 2016. Web. 16

Nov. 2016.

Wailer, Norman. “The White Negro.” Dissent Magazine. Dissent Magazine, 20 Oct. 2007. Web. 17 Nov. 2016.