My adolescence has been long haunted by sensations that I will never know: the bliss of biting into a dumpling made of whipped clouds, the warmth of jasmine bath waters, the serenity of a solitary train traversing a glass sea.

For these moments of unattainable euphoria I have to thank Hayao Miyazaki, esteemed director of animated classic, “Spirited Away.” Sensory snapshots like these, communicated through breathtaking imagery, are at once imagined and impossibly real—the mark of true fantasy. The film’s most arresting scenes are the transitional ones, the bits of stillness in between action, like the image of a placid lake cut effortlessly by a crossing train. The water is massless and unbounded, and the train’s motion is smooth.

a stunning landscape

It’s the lake’s sheerness that captivates us, and we catch glimpses of it in clouds, smoke plumes, or the redundant windows of city offices. We carry Miyazaki’s illustrations throughout our daily lives, animating mundane routines like eating, bathing, even riding public transportation with cinematic wonder and sublimity.

It is a movie you cannot forget, and one you long to relive in daily performance. As we return to our cubicles and screens, we wish the harsh florescent strips to be replaced with lanterns, bulbous and secretive. We imagine them emitting a haze that feels and looks second-hand, with the gentleness of a childhood nightlight, far gone and packed up in cardboard boxes. Suddenly, we are returned the scene of awakening spirits. Red lamps stir and awaken as shadows wander the festival streets. Slowly, we follow the movie’s heroin, a young girl named Chihiro as she explores the empty festival soon to be enjoyed by the gods.

So it’s a film that has been praised for it’s mastery of fantasy: it makes us feel things that are wholly otherworldly. It takes us to places and elicits sensations and emotions that are extra-human, and then prompts us to infuse them in every day life. Partly because it is so visually stimulating, the movie transcends the limitations of a target audience. Children and adults, homesick college students and their nostalgic professors, citizens of all nationalities and speakers of all languages alike have cherished the movie and its experience. But despite its success and reach, the narrative is structured around a relentless and multi-faceted moral statement, which is a rarity amongst popular cinema. (It is incredibly rare to find a cultural artifact accepted and popularized by mainstream media that is not forwarding a destructive ideology, but instead works to consciously undermine one.)

Most obviously, the movie holds humans accountable for their constant mistreatment of the natural environment, and it criticizes gluttony and greed. None can deny the underlying currents of environmentalism. We all remember the stink monster that enters the bathhouse, and when cleaned, is discovered to be a feeble river spirit. Chihiro undoubtedly leaves the bathhouse having learned lessons in hard work, obedience and the repercussions of avarice.

The disgusting stink monster

A bicycle is pulled from the stink monster’s side, unleashing a heap of trash

A river god emerges and thanks Chihiro for her service

But as my phrasing suggests, these conclusions are glaringly obvious. I reject the movie’s hook to be its fantasy, or any surface-level motif. To forward either as the main thrust of the film is to underestimate or disrespect the subtlety of Miyazaki’s writing. In truth, the film evokes themes far more insidious, far more trenchant, and far less recognizable. I assert that this movie contains incisive political threads, that are deeply rooted in its narrative and wholly involved with the cultural context of Japan at the time of cinematic production.

What is difficult to discern, and what will be the focus of this essay, is how the movie hints at the grisly pervasiveness of child trafficking in Japanese contemporary culture and history. The movie, stripped of its aesthetic beauty and child-like wonder and viewed through the eyes of a conscious citizen, is the story a young girl forced into prostitution by the greed and piggishness of her parents, a chilling and all-too-common tale. Thus, a movie especially adored by children for its splendor reveals itself to be a commentary on child prostitution.

Let’s break it down. The essence of the film lies in its dual premise. Conflict stems from the fluid interaction between two worlds: spirit, and human. In both realms alike, the good and the bad dwell together. The presumed oppressors of each sphere are not fully evil, just like the heroin is intrinsically flawed.

To continue it will be necessary to elucidate the dynamic roles of good and bad, starting with the human realm:

Human world:

- The bad: The movie opens on Chihiro’s family moving across the countryside of Japan. Immediately, Chihiro strikes us as annoying and puerile— the typical trope of the whiny 12-year-old girl whose softie parents have spoiled her all her life.

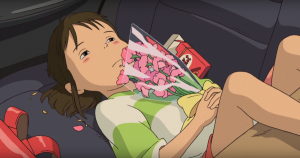

An apathetic Chihiro in the back seat of the car

Very mature, clearly

- The good: In contrast, her parents are portrayed as calm and patient, persuasive but not bossy. The mother’s voice is soothing and sympathetic, the father’s, assured and playful.

When the parents pull over to explore a side road, Chihiro is cowardly and uncooperative, while her parents are curious and adventurous (remarkably so, given that they have a pre-teen daughter). As the parents venture through the gates that separate the two worlds, their calm demeanors paint Chichiro as needlessly nervous.

Chihiro stubbornly nags her parents to come back

They tell her to wait in the car if she doesn’t want to come

She eventually follows, but clings to her mother’s arm

The parents sit down to sample a buffet, unknowing it has been reserved for the gods. If you’ve seen the film, you know this to be the screaming moment, when you want to throw your popcorn at the computer and warn the parents of the evil in those dumplings— satan in a sac of dough. But even to the knowing audience, the food is made to look so tempting, the chicken, so tender as it droops delicately from the father’s chopstick that we can’t blame the parents for their actions. In fact, many of us would choose those juicy chunks of ambiguous poultry over any of our own whining children, sisters or next-door neighbors.

yum

Meanwhile, Chihiro tensely bunches the bottom of her shirt, expressing her worry that they’ll get it trouble. Dad responds, “Don’t worry, you’ve got daddy here. He’s got credit cards and cash!” as he fills three heaping plates with food. She pleads for them to stop with the desperation of a desperate toddler in want of a sweet. And that truly is what Chihiro sounds like: a toddler. In a visual work where actors are replaced with drawings, the intonation and quality of the voiceovers carry incredible weight. Where we are unable to decipher emotion in the subtleties of facial expression—animation can only be so precise—we can in the characters’ voices. We can sense tenderness and innocence in their cadences, levity in their lilts. And Chihiro sounds like a whiny rascal of a child.

still yum

The parents ignore her protests and eat the food. Suddenly, they morph into pigs with disturbing human features (pig-dad retains his buzz cut and the pig-mom has her purse, still) and we realize this scene to be the fulcrum of the film’s conflict: the separation of Chihiro from her parents. Left all alone, Chihiro is forced to find a job at a bathhouse in order to survive as a human in the spirit world, and the rest of the movie progresses as she works to rescue her family.

In retrospect, the image of the parents’ pig-ification and those leading to it are wildly important: they symbolize the enslavement of Chihiro due to the gluttony and negligence of her parents. With or without realizing it, the parents sell their daughter into slavery for a few divine dumplings.

But the real kicker here is that Chihiro is not the helpless girl sold into slave labor by her greedy parents— rather, she is the whiny, hyper-sensitive child. The parents are the unassuming, innocent adventurers driven by opportunistic hunger. So the movie forces us to sympathize with them in the situation of Chihiro’s abandonment. (After all, we’ve all been tempted by that steaming plate of noodles before.) In fact, the moment is made to be so banal, and the parents’ actions, so understandable that we ourselves enact the indirect selling of our daughter into slavery.

What should be a moment of betrayal and abandonment becomes something of understandable coincidence: The parents just ate the food and then turned into pigs. And then Chihiro was left alone in a foreign world, forced to relinquish her name and free-will to the ruler of the bathhouse. It sort-of just happened. No ill-will involved. In simple terms, the effect of this situation is to normalize the circumstance of a child trapped in physical slave labor.

Going one step further, this scene does more than make Chihiro’s abandonment palatable to the viewer. It does more than absolve the parents of blame. The effect—by making Chihiro intolerably annoying, with a pouting grimace and a high-pitched, head-ache-inducing whine—is to make us believe Chihiro deserving of her predicament. It is to make us thankful for her enslavement, for her silencing. We are made to prefer her quiet whimpers to screaming protests.

While this is itself disturbing enough, the situation is complicated when we observe Chihiro’s response to her abandonment and how her actions are portrayed. She learns to scrub floors, deliver water tokens, greet customers. She learns discipline and tenacity. She braves flying paper monsters, scales the exterior of the bathhouse, runs along rusty pipes, and confronts a witch-like antagonist who’s giant face holds enough wrinkles for a small child to get lost in. She learns courage. She finds comfort in fellow bathhouse maids, learning camaraderie and trust. But by far the most persistent motif, she denies constant bribes from a lonely spirit called “No Face.” At every turn of the story, she declines money, treasure, toys, feasts. So, she rejects capitalism and materialism but endures forced physical labor.

Chihiro’s survival tale teaches viewers to value discipline, courage and hard work over greed. In Miyazaki’s own words, Chihiro “manages not because she has destroyed the ‘evil,’ but because she has acquired the ability to survive…” Thus, the film prompts young girls confronted with hardship, or left in isolation, to bear their strife with stoicism—to endure it. Don’t fight the evil, just do what you can to survive within your circumstances. In fact, Miyazaki praises the patience, and fortitude with which Chihiro accepts and submits to the labor she is forced into by her parents’ overindulgence. Indeed, amusement is the spectacle of strife, and the fortitude with which the characters bear it placates us to our real-world struggles.

The maids sweeping floors

and cleaning out the baths

and running across pipes

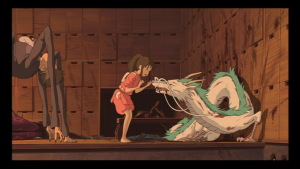

and caring for injured dragons

Though my fondness for the movie will never fade, it is difficult to see this story as one of mere slave labor when we are cognizant of Japan’s history of prostitution and sex trafficking. The country’s war-time narrative is marked by a painful, gut-wrenching report of sexual slavery. During WWII, hundreds of thousands of comfort girls were forced to service Japanese army camps, recruited through abduction or deceit, subjected to daily rape, and tortured if they disobeyed. Even after the war, the Japanese government established facilities that provided organized prostitution to expats of Allied nations. When in 1958 Japan made explicit prostitution illegal, soaplands, or in Japanese, sopu were designed for the men to be washed and sexually served by the female workers. A popular theory amongst internet super-fans, there are subtle implications that the bathhouse is a guise for such a Japanese brothel. Seeing that the only westerner in the film is the bathhouse overlord, Yubaba, who forcibly employs young Japanese girls and robs them of their names and tips, it isn’t unreasonable to view the house as an analogy for a Japanese whorehouse established apropos western occupation.

Given the resemblance between the bathhouse and the brothels of post-war Japan, we begin to remember the film’s subtle allusions to sex labor, like when the maids laugh wantonly as their skirts puff up in the wind, or when Chihiro is trapped in an elevator with the Radish spirit, whose giant tentacles we can take to be giant phalluses and whose heavy panting makes our skin itch, or when Chihiro’s name is contractually replaced upon employment, or the image of Chihiro pulling the single bicycle handle that has clogged the River God mistaken for a stink monster.

The girls run from the radish spirit

unfortunately he catches up to them…

But then we remember the strange relationship between Sen (Chihiro renamed) and No Face, a gold-producing monster. No Face is a lonely spirit who persistently offers Sen nuggets of gold, plates of food, anything to win her friendship. Yet she adamantly refuses all of his bribes.

No face offering Chihiro gold

and bath tokens

and more gold

This is telling. Sen’s genuine dislike of money starkly contrasts a conviction popular among Japan’s sex workers of the 90’s and early 2000’s, when the movie was in the height of production. On the cusp of the 21st century, a new wave of media coverage exposed the fast proliferation of schoolgirl prostitutes in Tokyo (where the legal age of consent was 14 at the time). Many journalists maintained that the increase in pre-teen prostitutes, described as a growing epidemic, was not due to the symptoms of poverty but to a culture of rampant materialism. A 1996 article in the Wall Street Journal paints the schoolgirl prostitutes as apathetic, vapid and brand-obsessed, insinuating that girls in the 2000’s began choosing prostitution to fund their expensive tastes for designer bags. This is a reality in direct contrast with images of war-time and post-war prostitution in the far east, which portray the battered “Oriental” girl, abandoned or sold off by her parents and forced to subject her body to the white man.

So the movie, as a cultural artifact whose context matters, is vacillating between contrasting images of prostitution, namely, the faces of its old and new manifestations. On one hand, the film endorses a mindset that enables a traditional version of prostitution, where one finds the means to survive in the event of her parents’ betrayal or death— where one endures suffering, rather than fighting larger evils. On the other hand, it simultaneous criticizes an attitude that fueled channels of prostitution circa 1996, namely, that of the petty consumer.

The movie includes both a praise of gritty perseverance in the face of undeserved abandonment, and a criticism of materialism and greed. The young girl of the past, coerced or tricked into prostitution is portrayed as noble and admirable because she endures her situation with dignity, while the young girl of today, tempted into prostitution by the allure of bags and brand names is vain and selfish, like the very slobbering pig-demons that consume Chihiro’s parents.

Prostitution is admirable when one is forced into it out of necessity, but wrong when one chooses it to fulfill her fate as a consumer. This is a movie about choice and the degrees of agency with which women conduct their bodies.

A more literal interpretation would uphold a bolder claim: Miyazaki is calling for a return to traditional prostitution with respect to its modern materialistic founding. He calls out the extravagance that is herding profligate girls into prostitution, and offers as its solution a revival of its older manifestation, wherein girls found the strength to survive in the face of adversity, where girls swallowed their pride and made not a single yen doing it.