So we are sent back to the passage already quoted, to scan it again for clues:

In the early 1920s, a number of people active in philosophy, sociology and theology were planning a gathering. Most of them had switched from one denomination to another; what they had in common was their emphasis on newly acquired religion, and not the religion itself. They were all dissatisfied with the idealism that still dominated [German] universities at the time. Philosophy moved them to choose, out of freedom and autonomy, what has been known since at least Kierkegaard as positive theology.

What jumps out now is that the men in question were all converts (not strictly true of the Patmos Circle, but perhaps true of the particular conference that Adorno is describing — who knows)? So maybe that’s the problem. But then why would that be a problem? You could begin by asking yourself: Do you typically have a beef with people who leave their religion for another — or who get God for the first time? Adorno also remarks that they had all converted in a Kierkegaardian spirit, and this might seem significant. Adorno, we know, was sufficiently interested in Kierkegaard to have written his PhD dissertation about him. So maybe that’s the problem — not conversion as such, just the Danish kind. Maybe that’s how we can tell the difference between the religious thinkers that Adorno warmed to and the ones he had no patience for. Rosenstock and Rosenzweig were existentialists; Walter Benjamin was not. But here, too, a complication opens up. Key figures in the Patmos circle were converts in the ordinary sense: Rosenstock was born into a secular Jewish family, but converted to Christianity as a teenager. The anti-fascist Protestant minister Hans Ehrenberg likewise converted from Judaism in his 20s. His cousin Rudolf Ehrenberg wasn’t exactly a convert, but was baptized Lutheran by his assimilated Jewish father, which is close. (Let’s poke around the family tree: Both Ehrenbergs were cousins of Franz Rosenzweig’s. And Rudolf’s niece was Olivia Newton-John’s mother. And Hans’s nephew was the father of the British comedian who created Blackadder.)

The problem is that if we’re talking about Kierkegaard, then conversion might not have its ordinary meaning. I’ll see if I can’t put across a few core Kierkegaardian positions, and I’ll emphasize the ones that mattered most to the existentialists. We can begin with the idea that you have to choose yourself. Society is the domain of conformity and routine and a muddled, huddling thoughtlessness. Chances are that on any given day, you just do what everybody else is doing. You do the expected thing. Nobody living under these circumstances, which is of course most people, is even remotely an individual. Your task, then, is to become an individual, and Kierkegaard has some strong beliefs about how you might go about this. The first thing to know is that philosophy won’t help. Philosophy, after all, is keyed to the universal; it wants to be able to make claims that will hold true for all people at all times — and that’s not a promising path for anyone seeking to individuate. Philosophy is just a more recondite way of becoming no particular person. The only way to achieve individuality is to be committed to something, to be fully dedicated to something outside yourself — though you can already tell from what I’ve just written that your commitment won’t proceed from philosophy and to that extent won’t be rationally defensible. You won’t be able to give compelling reasons for holding the particular commitment that you do — reasons that other intelligent people would have to grant are cogent.

Now Kierkegaard’s thinking on this matter is impeccably Protestant — and not just generically evangelical, but specifically Anabaptist, though that’s one of those explanations that probably needs explaining in turn. Anabaptism is the name for the Protestant sects who oppose infant baptism — who regard it as ungodly, in other words, to baptize babies, to induct newborns into a church without their consent and with no inkling of their actual standing with God. Baptism, on this view, is meant to follow on from a conversion experience, of a kind that a young child is unlikely to have and as a seal of one’s new openness to God — and as a cleansing, obviously, and a second birth. Ana- is a Greek prefix meaning “again” and refers to the early stages of the movement, when adult believers would have had to rinse away the false and infantile sprinklings of their native churches by getting baptized anew. The German word for Anabaptist means “re-dunker” or “double dipper.”

The thing to know about Kierkegaard, then, is that he was profoundly hostile to what we might call “cultural Christianity” — a society in which most people are Christian by default, because they were raised that way. (The last book he saw through to publication was his Attack Upon Christendom.) Conversion in the specifically Kierkegaardian sense might therefore involve leaving one church for another, but it needn’t. It might just mean committing with one’s whole being to the institution of which was already nominally a member. In this framework, conversion, commitment, and the second baptism group tightly together. Franz Rosenzweig thus belongs in Rosenstock’s company even though he didn’t convert to Christianity, precisely because he very nearly converted before deciding not to: “Also bleibe ich Jude. … It looks like I’m staying a Jew,” but for real this time — which is the sound of Judaism remaking itself on the model of Baptistry, a Judaism for born-agains.

Adorno, in fact, points out one of the more distinctive features of conversion — that it is chosen religion, religion practiced freely and by autonomous people. But then that can hardly be the problem. Surely freedom and autonomy are the very best things about the Kierkegaardian program. Let’s stick with the Anabaptists. The Amish famously tolerate among their teenagers all manner of ungodly behavior: wearing jewelry, signing up for Instagram, playing X-Box off of farmhouse generators, binge-watching Fast and Furious movies, gathering at the end of country roads to listen to hip-hop and drink Miller Lite. There is a general understanding, in other words, that a sixteen-year-old Amish person is not yet genuinely Amish and that the ordinary rules of Amish society therefore don’t apply. What’s at stake in this is perhaps best phrased like so: Being Amish is not an ethnicity. Americans at large tend to ethnicize the Amish, because Americans ethnicize everybody. The Amish even ethnicize their non-Amish neighbors and anyone who, like, drives a car, who are known collectively as “the English.” But the Amish do not ethnicize themselves. They are not “the Pennsylvania Dutch.” Young German-speakers in Lancaster County are only in some very qualified sense Amish, and their teenaged brothers and sisters are even less Amish than that, in a visible state of suspension, with the choice in front of them whether to be Amish or not. The creed of these horse-and-buggy traditionalists, then, is in core respects anti-traditional, premised on the conviction that custom is no-one’s fate, that heritage has claimed no-one in advance; and this goes back to a few of the key tenets of all sectarian Protestantism: that no-one can make you believe anything, that no-one should be forced into a church against their will or conscience. Milton called this the promise of “Christian freedom.”

The other point to make here is that critical theorists and their cousins have often written in favor of conversion. It is thus hardly obvious that a radical philosopher would have to look askance at the experience of re-birth. Three examples will clinch the case.

1) The core Sartrean position begins with the idea (again) that you have to choose yourself. You have to choose yourself; *and* you have to know that you have chosen yourself, you have to keep that idea in front of you; *and* you have to be ready to keep choosing yourself ongoingly; *and* you have to grant others all possible latitude to choose themselves. Conversion actually plays two distinct roles in this scheme: First, Sartre thought of Being and Nothingness — most of it anyway — as a close description of what it was like for a person to live without having arrived at this understanding. And his word for that arrival — for breaking through the reifying and identitarian delusions of ordinary existence — was “conversion.” A person, if she’s lucky, converts out of mauvaise foi. Second, nothing guarantees that I will continue to choose my personhood in the future in just the same way that I have in the past. (That’s a silly sentence, right? — because if there were a guarantee, then it wouldn’t be a choice. Sartre framing my selfhood as a perpetual choice has already abolished the guarantee.) The possibility always stands that I will encounter an “instant,” a moment of rupture, an ending-beginning, where my earlier project — my earlier personhood — is terminated and another one opens before me. The ongoing possibility and occasional reality of conversion vouches for my freedom, for a self that cannot be made intelligible via biography or some personal past.

2) For a while, Zizek was pushing a theory of what he called subjective suicide. Let’s start with the idea that all of us spend nearly all of our lives cocooned in ideology, social convention, and pseudo-sociological delusion — a set of more or less specious understandings of “how the world works.” Eventually, though, any one of us is going to have experiences that the social-symbolic order does not cover, and Lacanian wisdom holds that these experiences are bound to be deeply unpleasant, since anything that is compatible with that order will immediately get incorporated into it, absorbed into one of the pat narratives that we already tell about ourselves and our society, which means, in turn, that anything that lies outside that order is incompatible with it, ergo a threat to our ordinary understandings of the world and ourselves. Most of the time, these encounters with the Real don’t amount to much; they aren’t much more than eerie smudges on the screen of your experience. It is always possible, though, that an encounter with the Real will, for an interval, sunder your ties with the social-symbolic order, propelling you out of your accustomed social “reality,” and in the process obliterating all of your socially entangled perceptions of yourself: your “identity.” Lacan himself gives this experience the innocuous name of “the act,” which makes it all the more alarming to realize that the technical term for the resulting condition is “psychosis.” Zizek seems to get it right, tonally, when he calls it subjective suicide, though we might also just say: Sometimes you snap. Here’s Zizek: ‘The act differs from an active intervention (action) in that it radically transforms its bearer (agent): the act is not simply something I “accomplish”—after an act, I’m literally “not the same as before.” In this sense, we could say that the subject “undergoes” the act (“passes through” it) rather than “accomplishes” it: in it, the subject is annihilated and subsequently reborn (or not).’ This, then, is the Lacanian account of conversion: your temporary reduction to nothing; psychotic Anabaptism.

3) Badiou’s theory of the “truth-event” is the Lacanian act’s benign double. Sometimes — not often — we have an experience that strikes us as surpassingly important, something that hits us as anomalously true and real and right, an experience that leaves us feeling transformed and that suspends the normal order of the day: “This changes everything.” For Badiou, then, ethics is simply a matter of attending to those experiences — being open to them, letting ourselves be changed by them, and then resolving to stay changed, not to let ourselves bend gradually back to the norm and expectation and set-point. Until you have been called, there is simply no way for you to live morally. All ethics is an ethics of conversion.

All I mean to say here is that radical philosophy furnishes some rather attractive defenses of conversion, which means we’ll have to account for Adorno’s not following them.

Adorno also remarks that the Patmos group was religiously mixed; its members didn’t have a religion in common. He doubtless has this one gathering in mind, but his point would hold just as well for the New Thinkers at large. The Rosenstock-Rosenzweig correspondence is often held up as one of the twentieth century’s great feats of Judeo-Christian dialogue. Die Kreatur was published under the direction of three editors: a Protestant, a rogue Catholic, and a Jew (that last would be Martin Buber). It is hard to see these efforts as anything but a benignly ecumenical exercise. By the time Adorno wrote these words, Germans had been attacking each other on confessional grounds for more than four hundred years, often lethally: Schmalkadic Wars and Kulturkämpfe and Judenhetze. It will come as a surprise, then, to realize that this interdenominationalism is a big part of what is bothering Adorno.

We’ll have to keep reading to figure out why. The men in question had all taken a religious turn. A new passage:

However, they were less interested in the specific doctrine, the truth content of revelation, than in a disposition or cast of mind. To his slight annoyance, a friend [of mine], who was at that time attracted by this circle, was not invited. He was—they intimated— not authentic enough. For he hesitated before Kierkegaard’s leap, suspecting that any religion conjured up out of autonomous thinking would subordinate itself to the latter, and would negate itself as the absolute which, after all, in terms of its own conceptual nature, it wants to be.

I’m going to fill in a few details, and then we can see what they add up to. We know from Adorno’s papers that the friend in question was Siegfried Kracauer. If you’re reading that name for the first time, you could, just for now, think of him as the other Walter Benjamin, a second German-Jewish intellectual, close to Adorno, a good decade his senior, transfixed by popular culture in a way that Adorno manifestly was not, determined to remake thought around the experience of modern cities, and with a great many illuminating things to say about photography and film. (But then Adorno met Kracauer in his late teens, which means that in T.W.A.’s biography, he came first. Benjamin appears as a kind of second Kracauer. Also: You have to be able to imagine a Benjamin who was able to hold down a job at a major newspaper and who managed to make it out of France.)

Apparently one of the Patmos people told Kracauer that he was inauthentic. I’m sure you don’t need to be told that no-one was accusing him of being watered down to suit American tastes, like he was a corrupted version of Kracauer the way they cook it back home. The existentialist doctrine of “authenticity” tends to involve variations of the following claims:

-You need to know that you choose yourself, that you choose your identity, choose your way of living, choose your fundamental commitments. However you are, you weren’t just born that way.

-Equally, then, you need to be willing to own yourself — to be candid about your commitments and to take responsibility for your personhood, for your way of being in the world. The German word for “authenticity” — the one in Adorno’s original title — is Eigentlichkeit, which comes from the word eigen, which is the everyday adjective that designates something of one’s own: “I brought my own book.” “I brought mein eigenes Buch.” Its closest cognate in German is Eigentum, which means “property” — what you own. To be “authentic,” then, is to be your own person and to be willing to own the person that you are.

-If your fundamental commitments line up in some sense with those of your culture — and it is the hallmark of right-wing existentialism that it considers this always your best option — then the task in front of you is to be in some now fully committed way what up until now you had been unthinkingly. If you wake up at 17 and realize that you have been raised more or less as a Jew and that other people regard you as Jewish, then it is up to you to commit to your Judaism and to adopt it as a project. (And yes, equally: If you wake up at 17 and realize that you have been raised more or less as a Russian, then it is up to you to commit to your Russianness…) This is where the existentialist notion of “authenticity” rejoins vernacular concerns with race and ethnicity and bad Chinese food: You go from being an x to being a real x.

And then there’s this bit about “the Kierkegaardian leap.” That’s what English speakers usually refer to as a “leap of faith,” though Kierkegaard scholars love to point out that he never actually used that phrase. They also tend to object that the term, having first been invented by K’s Anglo-Saxon readers, then gets extracted from the ironies and pseudonymous obliquities of his writing and turned into some kitschy, blog-ready philosopheme — which is, of course, all the more reason for us to pay attention to it. The version that has come down to us mostly gets routed through the existentialist philosopher Karl Jaspers, who was one of the key figures in the Kierekegaard revival who will turn out to be one of Adorno’s prime targets in this book. It’s his version of the leap we need to know about here.

The first point to make about Jaspers is that he was a dualist: He thought that the human mind was bifurcated into two fundamentally different domains. Unlike many of his existentialist cousins, Jaspers had no objection to science and reason as such. They aren’t really the problem; they’re just grand as far as they go. There’s no reason to call into question what the scientists have figured out about non-human nature. Science will pass all but the most stringent epistemological tests. But if I say that they are grand as far as they go, then I am implying, of course, that they also have limitations. They can’t go just anywhere. Crucially, science and reason can’t tell us how to live — can’t tell us what to care about — can’t tell us what kind of people we want to be. I can become quite learned — I can bone up on string theory and evolutionary biology and the latest research into the Haitian Revolution — and I can reflect carefully on what I’ve learned. But none of this amassed knowledge can tell me what to do with my life. That’s the dualism: There are some problems, a great many problems, that we can approach with the tools of science; and there are other problems that we have to learn to think about in some fundamentally different way. For anyone interested in the history of philosophy, one of the more unusual features of Jaspers is that he thought of himself as a Kantian; he knew himself to be devising an existentialist Kantianism or to be offering Kierkegaardian answers to Kantian prompts. Kant’s first Critique vindicates science (and other types of empirical knowledge), while insisting that the mind will nonetheless press on, riskily, to some non-empirical notion of the world, the self (or soul or psyche), and God. Existentialism, then, picks up where science leaves off. What, after all, are we supposed to do about all those issues where science and knowledge can’t help? Maybe now’s the moment to pause to ask yourself: What is your basic orientation to the world? What other orientations would be possible? What are your fundamental commitments? Jaspers’s point — and this is how the “leap of faith” has often been understood — is that you are going to have to choose those commitments — some commitments, maybe an overriding commitment — and make your peace with your knowledge that this commitment is in some sense groundless: sorely under-justified. You’ve chosen *this* commitment; you could have chosen another. Jaspers has a lot to say about the dualism of science and commitment: about the danger of treating existential matters as matters of knowledge and the even graver danger of trying to duck those fundamental existential choices.

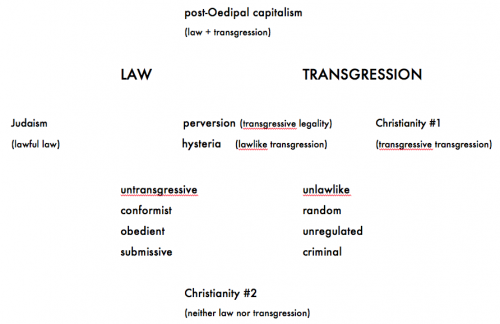

This last must be the accusation that was leveled against Kracauer, more or less: that he refused to grant that all convictions, including nominally secular ones, resemble religious belief; that he couldn’t bring himself to announce a commitment of a basically religious kind; that he thought maybe he could get by without commitments; that he was no leaper. Of course, Adorno also gives us — and implicitly endorses — Kracauer’s counterclaim: “He suspected that any religion that has been sworn to out of autonomous thinking would subordinate itself to the latter, and would negate itself as the absolute which by the light of its own concept it wants to be.” There are a few different issues that need to be teased out here. Adorno shares Kracauer’s exasperation with what looks like a contradiction in the existentialist position. To see this, we’ll need to bring into play the opposite of autonomy, which is heteronomy — the condition of being ruled from without — not giving-yourself-the-law, but having-the-law-imposed-upon-you. Adorno’s premise is plausible enough: He seems to think that religion is fundamentally an exercise in heteronomy, for which the Christian’s ordinary word is “revelation.” The law comes to the Christian from some external source: from the Catholic’s gradual training into Church tradition and discipline; from the scripturalist’s painstaking study of Holy Writ; from the spiritualist’s resolve to wait for God’s “leading.” Adorno’s point is that you can’t sincerely arrive at heteronomy non-dogmatically and via your own independent judgments. The existentialist gambit is to say that you can be a freethinker and still submit, and that your submission will not abrogate your status as a freethinker. And to this Adorno responds that if you retain a sense of yourself as a freethinker — if, following Jaspers, you never forget that you have chosen your commitments and could have chosen otherwise — then your commitment will always be provisional and indeed revocable and in that sense not really a commitment at all, certainly not an “absolute” one, one that you couldn’t imagine re-negotiating.

Of course, we can run the contradiction the other way. The heteronomy that the young existentialist agrees to mimic will require that he relinquish his freedom, punctually, over and over again, even as he tells himself that he is doing so freely. Existentialism thus resembles nothing so much as the voluntary servitude first described by La Boétie in the 1540s — or the condition that made Spinoza shudder, the confusion of people “who fight for their bondage as though it were their freedom.” Equally, we could think of this existentialism as a bizarre reversal in the history of Left Hegelianism. In the 1840s, Bauer and Feuerbach and others began arguing that religion was the very model of alienation: Humans had invented God; assigned to him their own most distinctive powers (the powers of spirit, of creation, their ability to make and remake their world); and then subordinated themselves to this distorted avatar of their own disavowed eminence. Left Hegelianism was obviously an invitation to drop the God-act; to recognize that God was a projection of the power of thinking human activity and so to affirm that power directly. The existentialists then arrived on the scene and took these arguments on board, only to say: That! Do that! Kneel to the god of your own making, even as you freely concede that this is what you are doing. Existentialism thus enshrines the alienation that it was supposedly designed to combat. It is the resolve to stay alienated even once you have gained insight into the sources of your alienation.

There’s another problem that follows on from this last and which Adorno has already insinuated at least twice: These early existentialists weren’t interested in any one religion, weren’t interested “in any specific doctrine.” So Jaspers says that we choose are commitments freely, and this will tend to imply that commitments are always plural — not that *I* will have multiple commitments, but that other plausible commitments were available and that I could have chosen differently and that I have to be prepared to let other people choose differently. Their choosing freely means they don’t have to choose as I do. This is Jaspers’s big innovation on Kierkegaard, who when all is said and done only had this one ardent version of Protestantism in mind. And though we might congratulate Jaspers for having figured out how to make Kierkegaardianism liberal, we might for that very reason fret that he has led us straight into the quagmire of multiple and contending Absolutes. We begin to sense the scope of the problem if we look again at Badiou, whose ethics is designed above all to undo liberal society’s general neutralization of commitment — its insistence that we not really believe what we claim to believe, or its grudging permission to believe anything we want provided we promise in advance never to do anything about it. Badiou, in other words, wants to teach members of a liberal society how to be fanatics again; he wants us to recover our lost capacity for militancy and Schwärmerei. The peculiar character of his argument, though, is that he is sticking up for fanaticism in general — for no particular fanaticism — and certainly not for communism specifically, which is what you might have thought he was after. And “fanaticism in general” is, of course, a broken-backed concept, a contradictory fusing of zeal and indifference: extreme and passionate dedication to a cause that doesn’t care anything about the cause. Badiou’s ethics thus incorporates the flaccidly noncommittal pluralism that it was designed to overcome, offering only a hollowed-out militancy remade on the model of its liberal enemy. Or to put the point more plainly: A genuinely religious person can’t care about religion in general, because he will be committed to the specific claims (rites, beliefs) of some particular religion. Particularity is built into the thing. Religion can only appear as “religion” to someone whose underlying premises are secular.