•1.

The only way I know how to make sense of the Iron Man sequel is to talk first about the original Godzilla, which is, in some complicated way, the later movie’s model and second precursor. Everyone knows that Godzilla had something to do with the nuclear bomb—that it was, like rocket-styled Chevys and bomb-expectant country gospel tunes, one of the key artifacts of atomic-age pop—but the point nonetheless needs to be clarified. So let yourself say the obvious: Without Hiroshima and Nagasaki there would have been no Godzilla. But then let me chime in that this is true in a way that is at once more straightforward and more complicated than you think.

A simple plot point gets us going: In Godzilla, the beast’s emergence is openly linked to nuclear testing in the Pacific. Nothing unusual there—variants on this conceit remained popular in horror movies throughout the ‘50s and ‘60s: that x-and-such a monster was caused by radiation. Usually, though, the idea had the character of a MacGuffin, a vacuous pseudo-explanation about which a given movie mostly didn’t care. And it turns out that this observation will hold for lots of different horror movies, in fact, and not just the radiated ones, since horror cinema has never been all that interested in what it is that makes its monsters walk: nuclear fallout, gypsy curses, chemical spills, ancient spells, passing comets, viruses, all of them more or less cursory and pretextual. This is what makes the ongoing debate among the fanboys over whether viral zombies are, because not technically dead, really zombies so inane, because in cinematic terms, back-from-the-crypt zombies and disease-bred zombies share pretty much everything but their pseudo-science, including the exponential logic of infection. Noting as much should make clear one of the things that is most unusual about Godzilla: It is one of those rare horror movies that really does care about origins. In lots of ways, it cares more about its atomic backstory than it does about the reptile’s morphology, which carries almost none of the former’s ideological charge. One way to start registering this point is to notice that the movie spends quite a long time allowing its characters to work through the nuclear explanation, showing Japanese people reacting to the news, following their debate about how to respond to this latest atomic threat. One man advocates keeping the information secret—not letting the world know that the country is still stalked by nuclear destruction—so as not to alarm Japan’s trading partners and political allies. The movie thereby registers the real Japan’s moment of nuclear repression or willed historical oblivion, its strenuous insistence, in the 1950s, on a Westernizing and post-atomic normalcy.

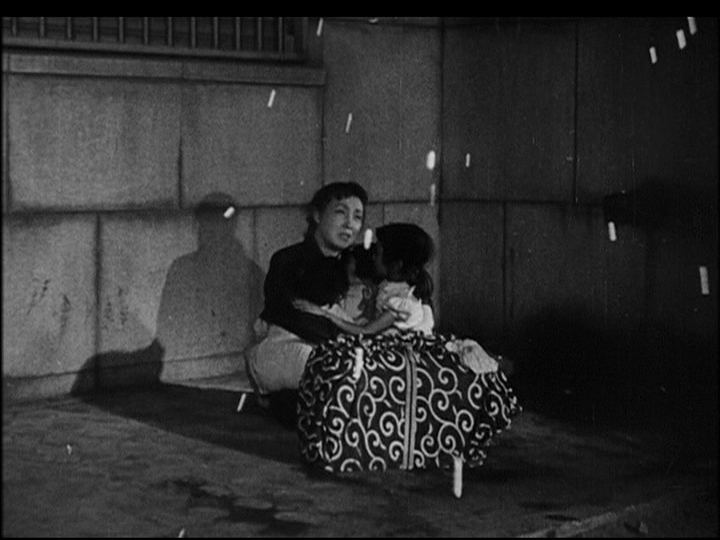

But then the movie itself serves to counter that very repression. The single most important thing about the monster is that he himself possesses the powers of nuclear destruction, and the movie’s most famous scenes are essentially one long re-staging of the Catastrophe: buildings tumble, entire cityscapes burn, medical workers check children with Geiger counters. When the monster breathes fire, the screen flashes and people shriek as they burst into flame. Refugees huddle. The movie seems determined, in some utterly straightforward way, to get on screen images from 1945, when this very directness would otherwise have been difficult just eight years after the war, setting out, as it were, to circumvent the psychic censorship that remained even after various official American bans had been lifted, performing the kind of end-run around repression that popular culture often undertakes—the service that stupid movies reliably perform for the political unconscious. The movie’s motivating fear, then, is easily named, which is simply that the bombs could hit again; that peace could evaporate; that it’s not over; eight years later and here we go again. The next time you hear someone say that horror movies traffic in “our fear of the unknown,” Godzilla is how you tell them that they’re wrong. When the movie came out, Nagasaki and Hiroshima weren’t even a decade back. Some people live in fear of the entirely known.

This is the sense in which the movie’s incorporation of its historical materials is almost alarmingly direct, without the intricacies and displacements that are otherwise the hallmark of allegory. And yet that allegory harbors a certain difficulty all the same. For Gojira, though unleashed by the atomic bomb, is not in fact a mutation, which is how you might have remembered the story. He seems, rather, to have been flushed out of some ecological hidey-hole when his coral reef got torched; he absorbed the bomb’s radiation and lived, like some indomitable and mountainous cockroach. But then what does it mean to turn the nuclear threat into a dinosaur or to let a prehistoric creature be the allegorical stand-in for the Enola Gay? This is all a little odd; odd first because it sutures together twentieth- century hyper-technology with something utterly primal; and odd, too, because the figure of the dinosaur—any dinosaur—calls to mind extinction, which in a nuclear movie means Our Possible Fate, but only if we think of the thunder lizard as a casualty (of a meteor, say, or volcanic gas from India) and not as the annihilating force. This peculiarity is evident in the movie in a small subplot concerning a paleontologist who doesn’t want the government to kill Godzilla; who wants time, rather, to study him, to work out how he has survived across the millennia. In one sense, this can be read as the movie’s meditation on “pure science,” in which the paleontologist appears as cousin to those real-world physicists who become fixated on the problem of fission in the abstract and don’t care that the nuclear winds are blowing across Nevada. And yet by allegorically making Godzilla a living creature, the movie generates a kind of eco-pathos for him that one couldn’t possibly feel for a warhead and indeed transfers to the Bomb itself some of the sympathy we might feel for its eventual species victims.

But then the movie also features a second scientist who also has marked affinities to Oppenheimer and Fermi, and it is with regards to him that the movie turns curious for real. The film’s inevitable question is: How can Gojira be defeated?—which we have to imagine also means something like: Can we imagine the overcoming of nuclear destruction? What is going to stop Japanese cities from burning again? And to this end, the film introduces a young physicist who has invented a fearsome technology, a small machine with the ability to suck all the oxygen from vast reaches of the ocean. He calls it an Oxygen Destroyer—and tellingly, he only ever says the words in English, even in the undubbed original, which phrasing associates the weapon with the US and so marks it as the-kind-of-infernal-device-the-Americans-might-have.

Here, then, is an unsurprising point: The movie features an unusually long debate about the ethics of using the machine—fifteen minutes that seem to have been scripted by the Union of Concerned Scientists. We can discern in this interlude a certain fantasy or thought experiment: a Japanese movie staging the debate that the Americans should have had with themselves and plainly didn’t. The local scientist, in fact, is determined not to hand over the technology—make a note of this, because that’s where Tony Stark comes in—and he seems to be modeling a moral relationship to science, a willingness to withhold destructive knowledge. In genre terms, this is rather fascinating: The physicist is plainly a Victor Frankenstein figure; the completely unexplained eye patch that he wears means that the movie wants us to see him as cracked and Gothic. But when he opens his mouth, he does not rave; he speaks instead with clarity, restraint, and concern, even as he stands there looking like a pirate in a lab coat. The mad scientist reflects on the ethics of technology and so crawls back from his genre-dictated insanity.

And now here’s the really surprising point: Having convincingly made the case for disarmament, the scientist then relents and agrees to press the death-button, and the movie mutates in an instant from an anti-nuclear broadside into an argued defense of mad science. I want to say this again, because I still don’t really believe it myself: The original Japanese Godzilla is not an anti-nuclear movie; it is in its own way entirely pro-bomb, rehearsing the agonized conversation over deploying such technology only to conclude that, yes, mass destruction is sometimes necessary to overcome threats that can’t be defeated by conventional armies.

But then it must be allowed that this decision is carefully framed and hedged. The scenario that the movie has identified has the character of an arms race or military competition or the structural compulsion to adopt the force of annihilation, and this is true because the readiest referent for “a threat that can’t be defeated by conventional military means” is itself nuclear weaponry. Godzilla is a stand in for the nukes, and so is the Oxygen Destroyer. The allegorical rebus reveals the same term on both sides of the equation. Dangerous technology can only be countered by dangerous technology. It’s the feeling one often gets watching Japanese movies or reading manga—that everything, once decoded, refers back to the bomb, every last robot and pixie and smurf. Hence the movie’s melancholy and its repetition compulsion: It is replaying images from war’s end because it can’t imagine a clear alternative in the present to the nuclear arsenal and is to that extent convinced that 1945 will ever be with us. It can’t imagine how to stand up to a nuclear power in a way that wouldn’t involve nuclear weapons.

So there is in the movie no authentically Japanese refusal of the atom. And yet Godzilla does nonetheless attempt a certain national solution: The scientist agrees that the weapon has to be used against Godzilla; but there is only one such device and he won’t share the blueprints; and then he dives into the ocean to confront Godzilla himself and refuses to resurface, thus ensuring that the oxygen destroyed will include his own. The movie, in other words, is trying to imagine the conditions in which a nuclear weapon could be used ethically, and its provisions are two: 1) That the weapon be utterly singular, not just single-use, since no bomb bangs twice, but irreproducible, incapable of being spread; and 2) that Oppenheimer be willing to strap himself to the bomb and ride it Kubrick-like to his own destruction. The notion that the Japanese have a more ethical relationship to destructive technology is thereby preserved in the movie, though in much modified form and not in the direction of a pacifism—just the contrary, rather—by resurrecting a few hallowed images from Japanese military history: the honor suicide, mostly. What the Manhattan Project lacked was the samurai code. The Japanese are more moral because they still have kamikaze.

•2.

It is important to keep Godzilla in front of us, because doing so is our best shot at noticing how fretful a movie Iron Man 2 really is, when we might otherwise mistake it for just another round of Downey-doing-his-thing: impish, blithe, getting by on muttery charm, a $200 million action movie with the cadences of screwball comedy—that’s what a lot of the critics said, and they were basically wrong. It’s the tone of the movie that the reviewers consistently bungled. “To find a comic-book hero who doesn’t agonize over his supergifts”—this is The New Yorker—“and would defend his constitutional right to get a kick out of them, is frankly a relief.” But nothing in Iron Man 2 breathes relief, and agony is in fact its prevailing mode, in a manner that is entirely at odds with the hero’s jive and patter, itself suspended for long stretches of the movie anyway. For Tony Stark is the Japanese scientist of the American Empire, the inventor who will not share his invention, the engineer who withholds the newest technology of death so that only he can command it: “You can’t have the suit. … I’m not giving you the suit. … You’re not getting the suit.” What the new movie shares with Godzilla is the notion that the perfect and ethical weapon would have to be entirely singular—there would literally only be one of them—and so would not be available for manufacture: a permanent prototype, forever in beta. Such is the importance of the many workshop scenes in both Iron Man installments, those oddly protracted sequences in which we watch our hero sketch and solder and glue. By investing the killer armor with artisanal qualities, as though ICBMs could be blacksmithed, they suggest that the weapon’s uniqueness could be maintained into the future, since it is the hallmark of any handcrafted object that it is in some strict sense unrepeatable. That’s a fantasy, yes, but it’s an unsettled one; unease is simply built into its scenario. The conceit of an unshareable weapon comes with a worry automatically attached, which is simply that one will become two. Arms proliferate, and then so do anxieties, in their wake.

It is this apprehension that Godzilla explores in its dialogue and that Iron Man 2 builds an entire plot around, which isn’t to say that the movies aren’t actually quite different. For the two Iron Men are both trying to imagine the imperial monopoly on violence, sovereignty at the level of the globe, force concentrated in American hands. This is the big difference between the old Japanese movie and its recent Hollywood counterparts, and it’s also why we can’t imagine Tony Stark heroically sacrificing himself—because imperial sovereignty requires that technological superiority be indefinitely preserved, on the understanding that it has desirable political effects, that it fosters order and lawfulness across the planet. Early on in the sequel, Tony calls this order by its proper name, which is the pax Americana. What’s remarkable, then, is that the movie can’t actually envision how the American peace is to be kept, even by its superhero and unofficial sovereign, to the point where either we have to think of IM2 as scrambling to keep its imperial fantasy running, and this in increasingly frantic and unconvincing ways, or we have to think of it as providing a spontaneous and unexpected dissent from that very fantasy.

Let’s just count the problems:

The most obvious threat in the movie is multipolarity, the simple idea that other actors in rival nations might have access to the suit and so might limit the American peacekeeper’s scope of action. Here the menace of a post-American world takes the form of Mickey Rourke’s Ivan Vanko, whose very body announces a Russia tattooed and resurgent, even as his mock-Ukrainian name smuggles into the movie memories of Dolph Lundgren and the Cold War inanities of Rocky IV. The Vanko-plot also provides the first good indication of just how nervous this movie is, because the Russian’s ability to improvise a pretty good facsimile of the Iron Man suit—to pirate, as it were, Tony Stark’s best handbag—means that the American is, in the movie’s own terms, just plain wrong, because he claims that other countries are years away from acquiring the technology, and they aren’t. The movie starts out from the premise that Tony Stark doesn’t fully understand the dangers of his own invention.

He understands some of them though, and from that perspective the movie is wary not only of foreign governments but also, and much more curiously, of the American one. This again goes back to a plot point: The people we most often see Tony Stark refusing to share the suit with are politicians and military officers. The anxiety here is in some sense easy to gloss, because it really is the Oxygen Destroyer all over again: Sharing the technology with the government would make it replicable and would put the design in the hands of the unreliable many. Indeed, to redesign the suit for combat would inevitably be to put it into mass production and so to make the weapon studiable by every battlefield scavenger and enemy spy. Committed to sovereignty at the level of the globe, the movie nonetheless resists centralization at the level of the nation—it doesn’t trust the U.S. government to inhabit its sovereignty well and worthily—which leaves it trying to conceive of an American imperialism without a strong American state. The empire can only perform its functions if there are private actors stronger than Washington.

That last point is going to have a certain type of reader crying Capitalism!—but you anarcho-socialists can just zip it, because the movie is every bit as wary of the market, which is, of course, the true vector of arms proliferation, the kindergarten classroom in which the nuclear flu spreads. It’s true that IM2 is a little muddy on this score, exaggerating an ambiguity that was already present in the first film. Initially, the movie fully commits to a vision of corporate rule and hence to a kind of Haliburton-speak: Tony boasts within the first ten minutes that Stark Industries has “successfully privatized world peace.” But the movie then shows him resigning from his own company and has him spend the balance of its running time fighting a rival arms manufacturer who wants his factories to start turning out suits in quantity, as though they were bike locks. Many of the newspaper critics complained that the movie was, in the usual manner of sequels, overstuffed or unwieldy; they accused the movie in particular of having too many villains. This makes the plot a little hard to keep up with, it’s true, but for once too-many-villains is very much the point, since Iron Man 2 is tracing out a certain problem, in the form of a network, whatever it is that connects the U.S. military to arms manufacturers to the foreign powers who also buy the Yankee guns. It is to this extent misleading to call Tony Stark a “supercapitalist,” as some of the reviews did, since he spends the entire film trying to keep his most important discovery off the market. The movie has as its center of gravity the notion that a certain class of objects should not become commodities.

But then—and here’s the real kicker—the movie doesn’t really trust Tony Stark either. If the first movie was telling a story about how a middle-aged playboy reinvented himself as a man of imperial purpose, then the sequel, which is careful to insert scenes of its superhero drunk, boastful, and reckless, is haunted by Tony’s bad behavior, hence by the possibility that the empire might backslide into loutishness. It’s a remarkable scene—the one in which Tony staggers around his Malibu house, suit on, visor up, laser-blasting holes into his own walls, recalling as it does, despite being set in civilian California, bad memories of some Manila bar, hooched-up sailors in port carrying their still loaded sidearms. The movie is thus able to internalize a dissenting view of US superpower, the perspective that colonized peoples have ever had of their occupiers, by allowing Iron Man to act out some of the American empire’s more minor crimes: U.S. soldiers taunting Iraqi children with bottled water; an American sergeant asking two uncomprehending Arab boys if they are going to grow up to be terrorist and gay.

So foreign powers can’t be trusted with the suit; and the US government can’t be trusted with the suit; and arms manufacturers can’t be trusted with the suit; and even Tony Stark probably can’t be trusted with the suit. A certain rift thus runs all the way through Iron Man 2. Visually, the movie continues to treat the suit as a techno-fetish or bucket full of whizbang, staging its best action scene in Monte Carlo and thereby ensuring we will spend the remainder of the movie seeing its hero as a kind of human Lamborghini. But in plot terms, the suit is less magic armor than monkey’s paw, a cursed object that produces more instability than it prevents. Iron Man 2 simply cannot work out a good relationship to its super-technology or to the dominion that such technology conveys.

…which isn’t to say that it doesn’t try. Its attempted solutions are two, one of which is easy to read but dumb, the other of which is much harder to specify—and also pretty dumb.

1) The business with Tony’s heart—the battery in his chest is poisoning him and he has to engineer a new one—is a tidy parable of recent oil politics and the search for renewable energy. The thing that fuels you will also kill you, and you will only survive if you can invent an alternate energy source. The idea is puzzling in many ways, all of which suggest how stuck the movie really is. First, Iron Man 2 tries to assure its audience that sovereignty has been restored to the American entrepreneur because in the battle for technological superiority he has acquired the next-generation model, the key to which is clean energy. This is something like the Obama-esque claim, endlessly repeated in the press over the last few years, that the US will maintain its global supremacy only if it can make (and patent) the breakthroughs that will lead the planet to renewable energy, if, that is, it can figure out how to run golf carts on eggshells and sewage plants on moonbeams. The movie’s version of the program is notable because it takes this run-of-the-mill futurism, which usually involves speculation about the American economy, and shifts it over into an openly military register, in the process laying bare the lethal dimensions of this green-capitalist fantasy, in which visions of ecological balance are yoked together with visions of permanent American ascendancy. But then this fantasy is hapless as it is lethal: the movie attempts a technological solution to its political problems having already conceded that technological monopolies of this kind cannot be preserved. Stranger still, Tony Stark only discovers clean energy because his dead father has left him its secret (in code!). American technological preeminence is thus framed as a passing of the generational baton, a paternal bequest, which invites us to think of sun- and wind-power not as an innovation—which is how we more typically conceive of it: the Solar Revolution—but as a simple extension of the past, a way of keeping the American Century going—and this from the position of 1974, the date on the message-bearing movie-within-the-movie that Papa Stark has left behind—a date here designated as the age of American hope … 1974 now, the year of Watergate and the oil crisis, with the Vietnam War long since turned sour and illegal. Iron Man 2 wants us to recapture the can-do spirit of the Nixon administration’s final months.

2) Late in the movie, Tony Stark says “I need a sidekick” and then addresses another character as “partner.” Lines such as these would require no comment in any other superhero movie, but in IM2 they announce a program, because the very word “partner” means that power is being shared, and if power is being shared, then Tony is no longer functioning as the classic sovereign. This gets us to the movie’s preferred solution, which is to provide Tony Stark with allies and collaborators, an extended support network, arriving in the form of cameos and subplots and independent action sequences, all of which contribute, no less than the multiple and redundant desperadoes, to the movie’s sense of overload. Scarlett Johansson is on hand, strangely doubling Gwyneth Paltrow, whose own role is nonetheless expanded and not diminished, and then Samuel L. Jackson appears out of nowhere, and Don Cheadle starts getting more lines. The movie is trying, in other words, to craft a situation in which the sovereign, the proprietor of the peace-creating superweapon, need not stand alone, in which he can count on others—buddies and semi-heroes—to back him up and keep him in check: a civil society of comic-book characters. But then perhaps “civil society” isn’t quite right, because the role of the state in this new justice league remains unclear to the end and is in fact adorned by a set a elaborate hedges and ambiguities. Let me just list the uncertainties:

a) Johansson and Jackson both play agents from something called SHIELD, but there is no way of knowing, on the basis of the movie alone, without separate consultation of Wikipedia or a fanboy, what kind of agency SHIELD is. Is it an independent superheroes’ union? Does the D stand for “department” or “division”? Division of what? The US government? The United Nations? Please tell me the H doesn’t stand for “Homeland.” When we learn that the organization is recruiting Iron Man, it’s impossible to say what it is he is being recruited to.

b) And then the movie rescinds this already unclear offer: SHIELD is not recruiting Iron Man after all, though it may occasionally consult with him in any additional sequels. So Tony is and isn’t aligned with an agency that may or may not be governmental.

c) In the movie’s final action sequence, Tony Stark fights alongside a lieutenant colonel from the air force, to whom he has in fact given a second suit, which is a clear sign that the movie has given up on trying to imagine non-proliferation and has gone over to devising scenarios in which shared technology is the solution instead. More: The last scene before the credits roll shows him receiving a medal from a senator at a government function. The movie comes surprisingly close, in other words, to drafting Iron Man into the US government—but then doesn’t. And this might suggest something like the “private-public partnership” that has been at the core of centrist political rhetoric for the last few decades, but that observation would be more convincing if Tony Stark were a properly corporate man, which he isn’t.

d) Even the basic meaning of the expanded cast is unclear. The network of allies could mean that sovereignty has been shared out and to some small degree decentralized, which would of course entirely change its character as sovereignty. Or it could mean that Iron Man is being worked back into some government-military command structure and thus reinserted back into a sovereignty higher than himself. And there is simply no way to tell.

This much I can say: There is no category of film more routinely scorned than the sequel. Sequels are formulaic, yes, and derivative and all but instantly shark-jumping—they import into film, at great expense, some of the worst instincts of network television—and they are of considerable analytic interest all the same—because whatever an original movie’s ideological accomplishment, a sequel will have to undo some portion of this if it is to have any story at all to tell, which means that even a moderately thoughtful follow-up will spontaneously have the character of self-interrogation or auto-critique. It will compulsively pick at whatever in the first movie’s ending was least convincing to begin with. The sequels that extend a hit movie into a franchise are also the agents of that movie’s unmaking. So the first Iron Man entry was as amiable a story about the American empire as Hollywood has yet produced. But Iron Man 2 speaks its doubts about American power and then can’t figure out how to get them unspoken. The film’s final sequence shows a terrorist strike on New York City—a big one, carried through to its ka-bam!, unprevented and set in motion by the arms race around the suit. But Downey kissed Paltrow, and you probably thought it was a happy ending.