Contemplating Contamination

Waste and Recycling at Williams College

By Marta Symkowick and Kaela Zarrillo

Introduction

Compost is organic matter, fit to be used as nutrients for plants. As stakeholders at Williams College throw away our food scraps and clamshell containers, this is what we envision our matter will become. Yet, animal bones, plastic forks, and metal knives that look like they came from Whitmans litter the massive piles of compost that make up the Casella Composting Facility, Bennington, Vermont. And these materials, especially plastic, do not escape the final product.

When the compost arrives at the facility, it is first run through a machine that sorts plastic and other types of trash, including plastic, out of the soil, according to Senior Business Development Manager at Casella Waste Systems Trevor Mance. However, not everything can be separated. Often the workers will pick out waste items from piles of compost that make up the wind row lined with piles of compost sits for two weeks. Compostable utensils are even more difficult because of their similar appearance to plastic utensils, and therefore, many plastic pieces remain in the final compost.

When we originally set out to pursue this project, we were interested in learning about Environmental Justice issues surrounding the use of the Hudson Falls Incinerator which is listed as the destination for end-of-life waste on the Williams College website. However, as we began to investigate further, we discovered that our waste management contractor Castella had not been sending waste to the location for some time. We also began to recognize the importance of contamination within waste management.

As Williams College pushes for zero waste, plastic waste often originates off-campus. However, after arriving, the waste is disposed of in several different ways, including paths created for this subset of refuse and also through unintended streams in the form of contamination.

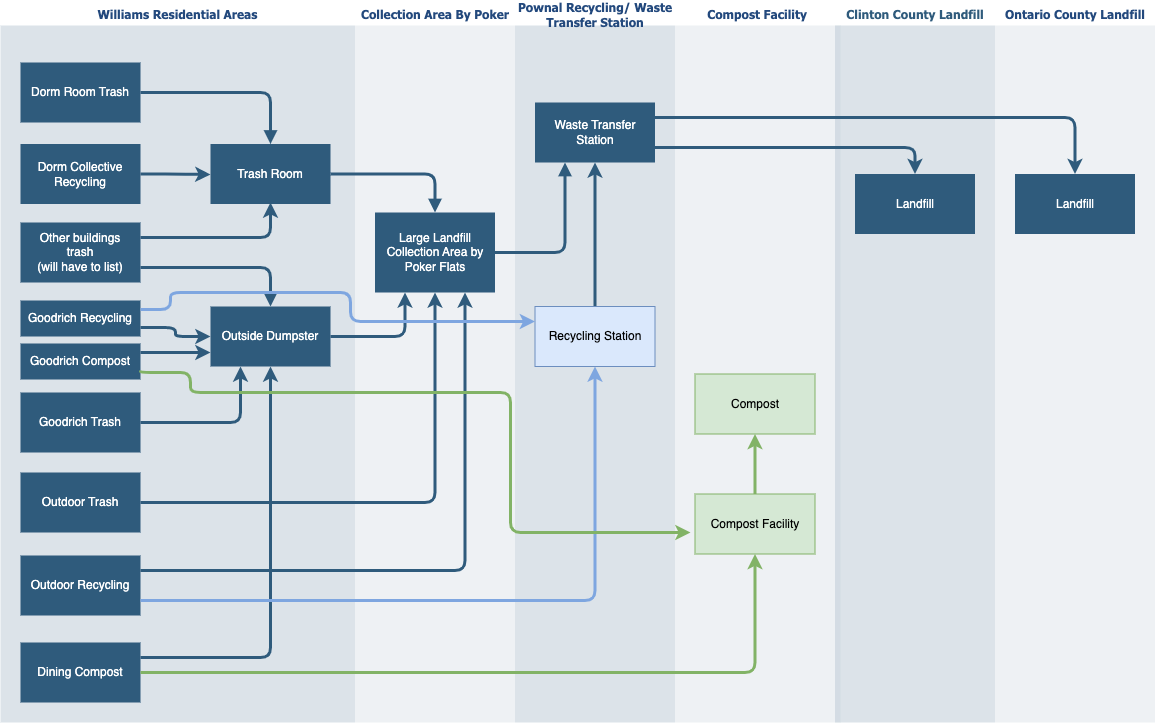

The flow chart illustrates the pathways of plastic waste, originating at Williams College. The dark blue arrows represent single-stream trash. The light blue and green arrows represent plastic waste in the form of contamination.

Williams College Residential Areas

Plastic waste at Williams College arrives from many different sources. No formal study contains data on where the main sources of plastic waste disposed of on campus come from. However, most individuals interviewed agreed that most of the waste originates off-campus. Pat Klugman, one of the two Zero Waste Interns at the Zilkha Center last summer, said their original thought was dining. “But then I thought about it, and dining doesn’t produce that much plastic,” he said. “I would say the overconsumption of Amazon, etc., from students, probably is the biggest source of plastic on campus. Because then that is just what is in the trash in their dorms.”

The other Zero Waste intern, Charlotte Luke, listed campus events that contain food, like club meetings and department get-togethers. She also reflected that she believed most plastic originates off campus, citing the plastic to-go containers from different restaurants. However, wrappers and plastic bottles from vending machines are also a major source of plastic waste, according to a member of a residential custodian that collects waste from individual bins within buildings and transfers them to waste rooms.

Designated places for trash disposal, including bins, are all over campus. The trash from dorm rooms and most other indoor locations, including Sawyer Library, is first taken to trash rooms, often found in building basements, by the different residential custodians, according to the custodian. A separate custodial team then transports the trash to the Williams College Collection Station.

Overall, this initial collection of trash is relatively straightforward. However, the member a residential custodial team reflected that there are actions that students can take. “I guess the biggest thing would just be like, if you’re throwing bottles or cups and stuff make sure they’re emptied first before they go in,” they said. “[The bottles] often end up upside down and then it sinks to the bottom of the bins and gets all over the floor.”

Yet, plastic waste does not only end up in the trash. Many of the individuals interviewed mentioned contamination within recycling streams, although to varying degrees. The residential custodian mentioned that they only had to throw away recycling due to contamination once or twice per week. While a conversation with a member of the outdoor recycling and team yielded a nine out of 10 contamination rate.

Plastic waste also contaminates compost. Klugman also works at Goodrich, and part of their job is taking out the compost. “Nine times out of 10 when I’m bringing the compost, either I dig my hands in, or I just put it in the trash,” they said. “People also thought you could just put the entire bag of compost into the dumpster, but it’s all contained in a plastic bag so you have to dump it. And people just didn’t know that.”

Pat also reflected on why the contamination rate is so high. “I do not think there is enough education on this campus surrounding what is recyclable or not,” he said. “Education is a larger issue that I don’t think was really included within the bin standardization position project, although I’m looking back on that, and it should have been. Maybe moving forward it could be for whoever students are zero-waste right now.”

Recycling at Casella’s transfer station in Pownal, VT.

Williams College Collection Station

Trash is transported from the trash rooms and cans it accumulates in across campus. Assuming they end up in the trash, the (compostable) plastic utensils along with plastic waste from Amazon, food packages, and to-go boxes from dining halls and Spring Street businesses will be taken from the trash rooms in plastic bags to the waste shed we visited during our first field trip of the semester. While we had initially expected the area where all of the trash ends up to smell just as sharp, sour, and sickly sweet as the trash rooms they came from or the trucks that transported the trash bags there, it was surprisingly neutral. Everything is extremely organized, with compost being placed in bins with wood chips over top, e-waste and hazardous waste under cover of the waste shed that gives the area its name, and trash and recycling bags placed in large dumpsters at the back of the lot. This area is primarily for compost or recyclables, but if either is contaminated with too much trash (notably, if the recycling has too much dining hall waste – clamshells or compostable silverware) it is thrown away with the rest of Williams municipal solid waste.

In a conversation with Ricky Harrington, he discussed the specific introduction of recyclables and plastics to municipal solid waste due to contamination – usually caused by students or staff throwing trash into recycling bins. “ …the contamination rate is low. So I think last year, our contamination rate was 3%. And on average, Brian from Casella says 5% is the national average. So we’re below the national, we’re doing really well as far as that goes. And that’s with a lot of challenges like with the masks always ending up in there and those clamshells. So, I think we’re doing really well.” The only information verifying this contamination rate comes from a sparse email sent to Ricky Harrington from Brian Mattes at Casella: “We talked with our manager at the transfer station on that and your material is excellent as far as contamination rate 5% or less”.

Pile of municipal solid waste at Casella’s transfer station in Pownal, VT.

Pownal Recycling/Waste Transfer Station

All of the municipal solid waste is transported to the Casella transfer station in Pownal, VT that we visited a couple of weeks into the semester. It is transported there by Scott Smith and has been for, give or take, thirty years. The transfer station is also notably contained. After driving over a small platform that weighs trucks as they come in to deliver trash and recycling, you can enter a small warehouse-like building that houses the waste. The smell at first isn’t bad, it mainly smells like damp cardboard, with maybe a few whiffs of a sharper trash smell hitting you occasionally. This first room is where recycling is packaged into cubes tied up with metal strands to be more easily transported. The room in the back is where the trash is dealt with. It is LOUD with the sounds of machinery and the occasional explosion of a crushed milk jug hitting your ears. The smell here is much more pungent – imagine a dorm trash room’s smell multiplied five times over, with much more complex sour and strong odors. It is from here that Williams’ trash is mixed with trash from all over the surrounding area and is transported to one of two landfills – Ontario County Landfill and Clinton County Landfill.

After speaking with Richard Smith of Casella, we learned that only a small percentage of Casella’s total waste comes from Williams College – 6% to be exact. Smith “estimate[s] about <10% recycling/plastics comes in with household trash.” However, there is no specific data regarding this since “it all gets processed as trash.”

Unfortunately, no one we spoke to at the college seems to know much about the landfills at all. Miscommunications have led many people to believe that Williams’ trash is sent to an incinerator in Hudson Falls, NY. However, this was discontinued.

Casella garbage truck unloading municipal solid waste at Casella’s transfer station in Pownal, VT.

Moving municipal solid waste into a smaller area.

Clinton County Landfill

Some of the college’s waste goes to Clinton County Landfill. It is located in Morrisonville, NY, and is 170 miles away from the college. It covers 70 acres and operates as a “Gas-to-Energy” landfill, meaning it collects and destroys methane emitted from the waste collected there. This is a sustainable option for landfills.

We had hoped to get first-hand information from the Clinton County Landfill but faced great difficulty getting in contact with them.

Ontario County Landfill

A percentage of our waste goes to Ontario County Landfill, located 234 miles away in Stanley, NY. Ontario County Landfill is a 389-acre development.

The New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) just fined the landfill $500,000 for Air and Water Quality Violations From 2015 to 2022 in November of 2022. $250,000 will be paid to the city of Geneva for an Environmental Benefit Project, $220,000 will be paid to the state, and $30,000 will be suspended.

In the department’s press release, NYSDEC Commissioner Basil Seggos said, “This enforcement action holds the parties responsible for years of violations and will invest in the community and Seneca Lake by directing a portion of the settlement to the city of Geneva to install a biofiltration system to treat odorous air at the solids handling system.”

We have also tried to contact the facility, however, they have thus far been unresponsive as well.

In Conclusion

Our project did not go at all how we expected it to. After initially setting out to investigate the Hudson Falls incinerator and coming to a dead end, we had to restructure our entire project. However, seeking information towards where our waste actually went – the two landfills – proved to be extremely difficult as well. We instead decided to grapple with the issue of contamination. As waste is defined as “Matter Out of Place” by Mary Douglas, it is ironic to discover that even within the waste stream itself, contamination exists and even more surprising to discover the varying sources of information surrounding this contamination. Thus, information regarding waste at Williams should be much more transparent for students, as well as for everyone involved in the waste disposal process.