Blood, Sweat, and Tears: An Inside Look at Medical Waste at the College

Jack Marquardt and Kiara Royer

“For [something] to be considered true medical waste, if you went like this with it [he pretends to wring something out with his hands], and it dripped onto the floor — it would be blood or some other type of body fluid,” Health Services Administrator Bob McBain said. “If it was that much body fluid, then that’s considered medical waste.”

How do we define medical waste? Ever wonder where used needles go at the College? Where does gauze from football games end up? And how can we improve the treatment of medical waste after it leaves Williamstown? Keep reading to find out!

What is medical waste?

“Medical waste is a subset of wastes generated at health care facilities, such as hospitals, physicians’ offices, dental practices, blood banks, and veterinary hospitals/clinics, as well as medical research facilities and laboratories. Generally, medical waste is healthcare waste that that may be contaminated by blood, body fluids or other potentially infectious materials and is often referred to as regulated medical waste.” – United States Environmental Protection Agency

——————————————

“It’s abrasions, it’s lacerations, so it’s a lot of blood cleanup more than anything else…band aids, gauze, gloves that have touched any of that…So in terms of defining it, I don’t have a really clear definition for you, other than I know it when I see it — anything that comes in contact with bodily fluids, or waste we would classify as medical waste and dispose of it in those those containers.” – Rodd Lanoue, Director of Sports Medicine

“I can’t decide if medical waste should be thought of as gross and gooey or as clean and tidy. I feel like the Doctor’s office is always clean but I also feel like medical waste is probably as germy and unsanitary as you can get.” – Carter Anderson ’25

“Anything that needs to be thrown away after being used in some sort of medical setting — anything that can’t be reused.” – Gwyn McLear ’24

“Medical waste is unneeded byproducts of medical care.” – Omar Ahmad ’23

What does a lifecycle of a needle look like?

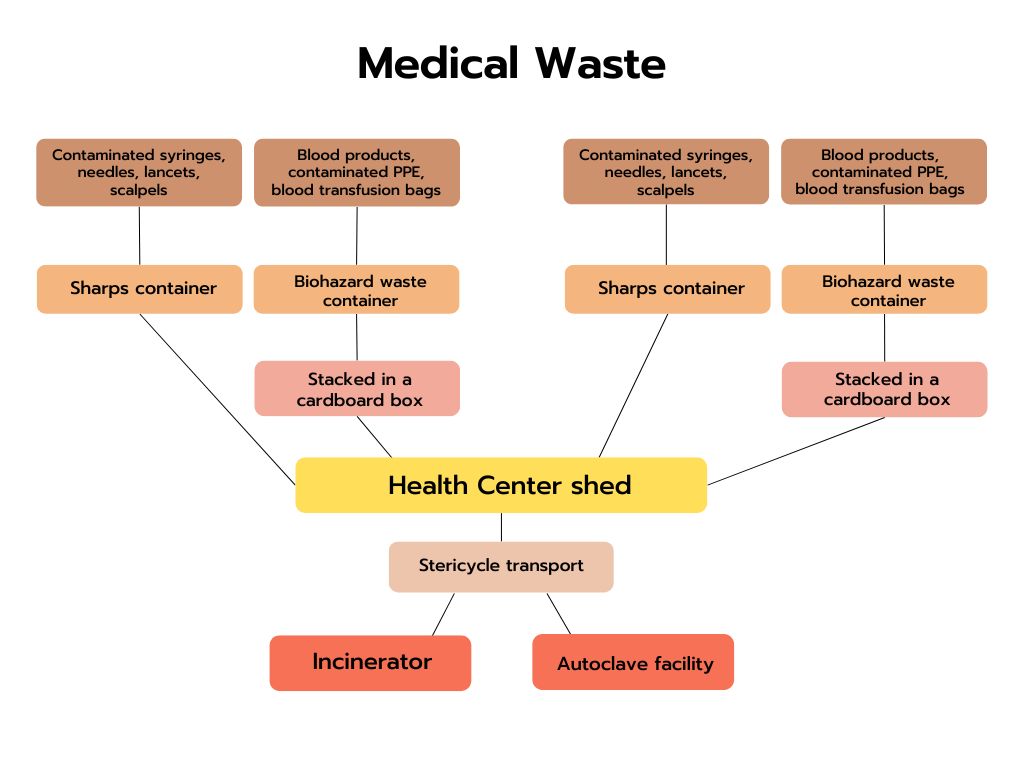

Let’s next follow the lifespan of a needle. A student arrives at the Health Center for an appointment. Wearing gloves, a nurse uses a single-use needle on the student and then disposes the needle in the sharps container, a red, puncture- and leak-resistant disposal receptacle located in every Health Center exam room.

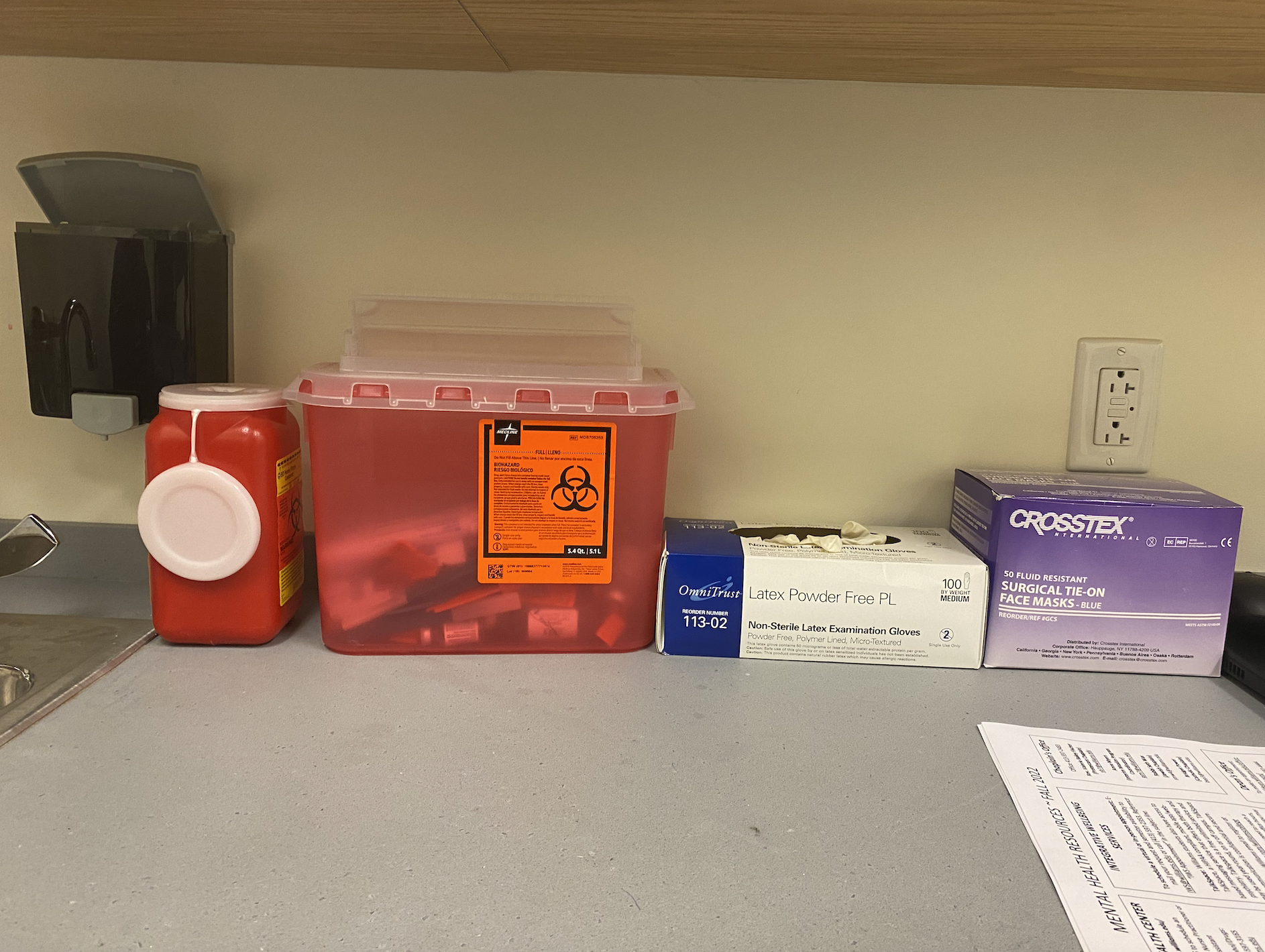

Every exam room at the Health Center and athletic training room has a sharps container for “sharps” materials.

A majority of the medical waste at the Health Center is “sharps, which is a needle that was put into somebody, and then it gets put away properly in a sharps container,” Bob McBain, Health Services Administrator at the Williams College Health Center, said.

Director of Sports Medicine Rodd Lanoue said that athletic training rooms also boast sharps containers. “We have a couple of different styles — there’s a skinnier, taller one that you can drop scalpels in or syringes very easily, and then we have a large one with a flip top door,” he said. “It’s kind of like when you’re mailing something, right, [and] you can’t like stick your hand in the FedEx box at the same time that you’re trying to push [an envelope] down.”

Besides the sharps containers, both the Health Center and the athletic training rooms also have collection containers for medical waste not considered to be “sharps.”

Every exam room at the Health Center and athletic training room also has a biohazard container.

“We have collection containers, which are the red biohazard certified cylindrical cans with biohazard bags in there [he points to one located behind us] that we would put anything that we deemed as medical waste, which, you know, include band aids, rubber gloves, gauze, all those soft types of things,” Lanoue said. “Used COVID tests was something else that we were disposing of in our biohazard waste. All of that goes into those classic red biohazard trash bags that are inside those containers.”

“When [the containers] seem to be getting full, and — full is one of those things where it’s medical waste, so you’re not sticking your foot in there to get the trash down,” Lanoue continued. “When they’re looking sort of full, right, like three quarters of the way full, that’s probably good enough. We seal with athletic tape, because we’re in the athletic training room.”

When both of these containers are full, a member of the Health Center will then bring the containers to an inconspicuous green shed located outside of the Health Center entrance. “It goes in a bag in a box,” McBain said. “It’s a highly regulated bag in a box.”

The Health Center shed holds filled waste disposal containers from the Health Center and athletic training rooms.

Lanoue said that although he has the option to call Campus Safety for transporting the containers from the athletic training rooms to the Health Center shed, he tends to use his own vehicle. When asked if he had any reservations in doing so, Lanoue said no. “Personally, I do not because the bags are sealed,” he said, further commenting that the brief transportation time and distance factors in.

What happens after the waste ends up at the shed?

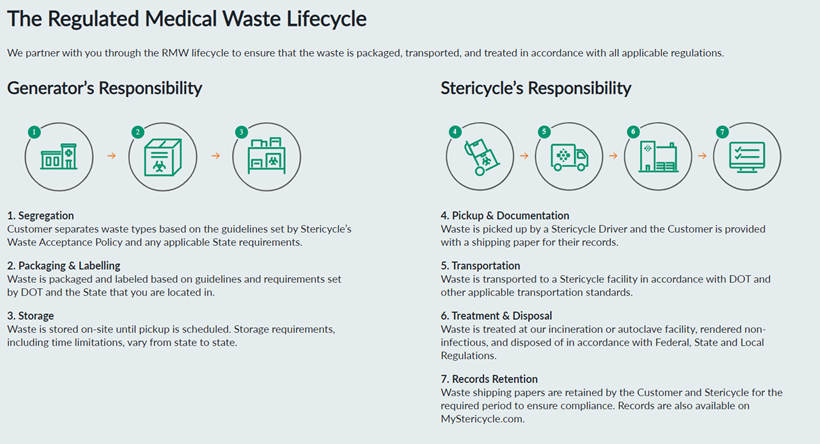

Stericycle, a national waste treatment company dedicated in disposing medical substances, then picks up the boxes from the Health Center shed four times a year for proper disposal. “There are all these stickers we put on [the boxes], so [Stericycle] knows what came from here, they know exactly where it came from,” McBain said. “They are tracking it to make sure that we’re not just taking this stuff to a dump and throwing it out, so it’s all tracked pretty well.” In total, Stericycle collects ~77 pounds of medical waste from Williams on an annual basis.

Stericycle is one of the largest medical waste management vendors in the world on both a waste processing and a revenue basis. Because of the stringent Federal and State regulations that it helps its clients adhere to, it is able to command high prices and has low turnover rate.

Stericycle has several mechanisms for safely treating and disposing of medical waste: autoclaving, incineration, landfill disposal, and recycling. Though it has access to all of these processes, autoclaving is its most frequent method for taking care of medical waste — accounting for 54% of its waste. We can safely assume that the majority of Williams’ medical waste is treated via autoclaving. We know this because autoclaving is considered to be the primary method used for “red bag waste” — gauze, bandages, needles, and gowns — the primary forms of waste that Williams deals with on a regular basis. (https://www.redbags.com/incineration-vs-autoclaving/)

While it is not perfect, autoclaving is relatively safe for the environment. This process involves the use of very hot steam to sterilize medical waste — a process capable of killing germs that cannot normally be harmed by simple boiling water. While it is not an appropriate choice for chemical waste, it is an environmentally and financially suitable option for Williams College’s purposes. Unlike autoclaving, incineration is an energy intensive process that often involves the burning of plastic — a process that can result in the release of toxic fumes. Given that incineration is typically reserved for more complex pieces of medical waste — such as trace chemotherapy waste and pathogenic samples — we can assume that the Williams Health Center does little to directly contribute to the negative externalities associated with incineration. However, labs that are ordered by the Health Center and then transported to Berkshire Health laboratories might end up being treated via incineration.

Takeaways

1. Interviews with non-medical professional Williams community members suggested that there is no standard consensus on the perceived definition of medical waste and its physical qualities. Some community members assumed that medical waste has the presentation of sterility while others assumed that it exuded the exact opposite. This might make sense though, as the term “medical waste” is expansive.

2. Though they are both code-adherent, the Health Center and the Athletic Department have different approaches to medical waste. The Health Center has a “higher bar” for classifying waste as “medical waste” and is less likely to classify bandages and used Covid tests as medical waste. Whereas, the Athletic Department is more likely to set a “low bar” for medical waste and to classify most items that come in contact with human skin/fluids as medical waste. These diverging approaches speak to the reality that individual department heads have different comfort levels with contents that come into contact with other human bodies.

Potential Next Steps

1. Explore the possibility of standardizing the definition and treatment of “medical waste” between the health center and athletic facilities.

2. Further explore Stericycle’s processing of medical waste and do a comparison analysis between other competitors.