Construction and Demolition at Williams College

by Desel Dorji and Hannah Dubb

Intro to C&D at Williams (run by the Planning, Design and Construction department)

We looked at the waste stream for C&D (construction and demolition) waste. This may include:

- Metal, wood, cardboard, concrete, and gypsum (i.e. drywall) from construction sites. There is a separate waste stream for hazardous/toxic materials.

-

- Deposited in onsite dumpsters (see flowchart)

- At Williams specifically: waste produced in the routine maintenance/renovation projects by Facilities (i.e. dorm furniture that’s being replaced).

- Deposited in dumpster at college waste shed.

- A small amount of municipal solid waste (MSW) that comes from project sites and offices

Capital vs. non-capital

At Williams, all construction projects are divided into two categories. Capital projects are those that cost upwards of $5 million, and non-capital projects refer to all those that fall under this figure. While the capital projects are considered in the context of the college’s master planning framework, the non-capital projects all compete for a pot of roughly $12 million dollars. Members of the college community can fill out a capital improvement request which will count as a non-capital project. These requests are reviewed yearly, and the PD&C places priority on those that involve safety concerns or accessibility issues.

Living Building Challenge & LEED

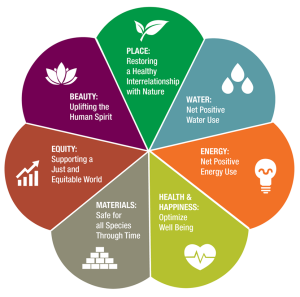

Currently, the college follows two main certification programmes. The first is the Living Building Challenge (LBC), which was created by the International Living Future Institute (ILFI), and the second is Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED), created by the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC). Projects costing more than $5.3 million are supposed to aim for at least LEED Gold certification. Both LEED and LBC provide a rating system for new buildings and construction projects in relation to impact on the environment.

The LBC petals (Source: Williams Class of ’66 Environmental Center)

LBC red list

ILFI created a document titled The Living Building Challenge (LBC) Red List, which it claims “represents the ‘worst in class’ materials, chemicals, and elements known to pose serious risks to human health and the greater ecosystem that are prevalent in the building products industry.” The list, which is available on its website, lists 5814 such materials, chemicals, and elements under 19 chemical classes which are expected to be phased out completely from construction.

Williams College Design Standards

The college has compiled a document that specifies the design standards by which each project is expected to abide by; as the standard states, “compliance with the Williams College Design Standards is mandatory for new projects, renovations, and ongoing maintenance”. It lists everything from which color chalkboards and brand of dry-erase boards must be purchased to specifications on the college’s heating operating standards and quality control of landscape development work. While it does not explicitly reference the LBC red list or other similar external guides, the PD&C suggests updates to this document based on its compliance in other projects with the LBC red list and other such standards.

Waste diversion

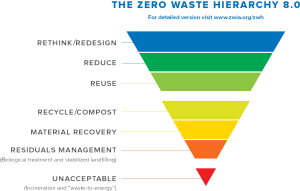

In construction and demolition (C&D) work, waste diversion refers to all the materials that are no longer needed on-site but are not sent to the landfill. Diversion rates are something that came up often in our conversations, a quantifiable measure of one’s sustainability efforts in C&D.

The Zero Waste Hierarchy, first shown to us by Mike Evans (source: Zero Waste International Alliance)

In our research, we spoke to:

- Julie Sniezek, a project manager in the Office of Planning, Design & Construction (PD&C) at Williams. She has been involved in multiple capital and non-capital projects, and the one we spoke most about was Fort Bradshaw, which was completed in 2021

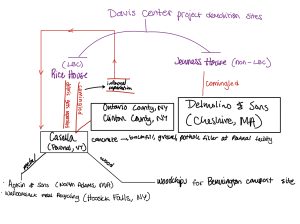

- Scott Henderson, a Williams senior project manager at PD&C in charge of the current Davis Center project

- Mike Evans, the Deputy Director of the Zilkha Center for Environmental Iniatives at Williams

- Ryan Dodge and Steven Chan, two employees of Consigli Construction (Williams’s contractor for the Davis Center project)

- Richard Smith, operations manager at a materials recovery facility (MRF) in Southern Vermont (the recipient of some Williams C&D waste, including some from the Davis Center project).

Defining Waste

A surprisingly complicated conversation that has come up in our class was how each of us seems to define waste differently. Here are five more definitions of waste that were offered to us in our interviews.

- Oxford English Dictionary (def. II.5.a.): Useless expenditure or consumption, squandering (of money, goods, time, effort, etc.).

- Scott and Richard’s definitions (as listed below) are interestingly rather different from what many of us in this class used when writing our “dreck diaries” (records of waste). Our classmates tended to record everything disposed of—whether in the compost, recycling, or trash—as wasted material. People thought they were wasting material insofar as the material could no longer be used by them, and their knowledge of diversion/non-diversion rates was limited.

- Richard, who has worked in the waste industry for many years, also provided a very succinct definition of waste as “something you throw away and forget about.” He recognised that ways of defining waste are up to the individual; after all, food waste that is easily discarded by some people (and subsequently forgotten about) can also be food “waste” that is diverted to compost.

- Scott: “Like right now we have two dumpsters. One I would consider waste. It’s just debris from general construction and there’s going to be bits and pieces, containers and things like that, that just can’t go anywhere except, unfortunately, the trash. Versus the other dumpster which right now is full of wood that will be recycled in some way.” (similar to Richard)

- When speaking to Julie, we were careful not to use the word waste because we identified in our preparation that we wanted to see in what contexts our interlocutors decided to use the word to understand the implications of their choices. In our conversation, however, the word waste came up only 4 times. 2 of these mentions of “waste” came from Julie, and the other 2 were mentioned by us in our questions to her. The first time she mentioned waste was in terms of demolition, as she noted that when demolishing you have to “knock a building down, scoop it all up, and throw it away to a commingled waste hauler.” This clearly delineates a specific type of waste, one that is determined by the method of disposal; only those materials that went into one specific hauler were labeled as “waste”, the rest of the products of demolition were referred to by their names because of the recognition that they could still be used.

Flow Chart

Waste stream for C&D materials at Williams

Compost piles covered in wood chips (Bennington, VT)

Human and environmental effects

Transporting the waste

As Richard told us (while acknowledging that there are a good number of people who are willing to transport waste): “The cleaner the material, typically, the more willing people [are] to…deliver that.”

Human labor is an intrinsic part of the waste disposal process. As we observed in our many field trips and interviews for the class, even more automated processes require human oversight. Non-diverted C&D eventually ends up mixed with municipal solid waste (MSW), yet by design Williams C&D is segregated from MSW both on its containment on campus and modes of transportation off campus. The ease with which people seemed to distinguish leftover construction materials from MSW or other such types of “waste” speaks to this impression of C&D waste as “cleaner.” Even in our class, there was a clear difference in the way we walked through the area in which the Castella MRF was sorting out its MSW and the area that contained piles of construction materials. However, C&D waste (even diverted materials) are not considered as clean as new materials, or materials that never carried the label of “waste.” For example, Scott Henderson remarked that if he were to try to give diverted material to the Habitat for Humanity store (as sometimes happens), he wouldn’t call the donation “waste”: “I’m sure we wouldn’t call it that. Because we’re trying to give it to someone.”

Part of this seems to be explainable when thinking about it in terms of affect theory. Affect implies that a visceral reaction is necessary for the formation of negative emotions such as disgust – no really visceral experience of C&D occurs, aside from safety/danger. Even the toxicity of materials is one gradually experienced, not an immediate sensorial experience. In other words, C&D materials are not offensive to our bodies in the same way that other types of waste are. C&D may be considered “cleaner” because it is not as odorous as, say, rotting food. However, it must be noted that a heavier odor making something more disgusting (“unclean”) is itself to a degree socially constructed. As William Ian Miller writes in The Anatomy of Disgust, “Emotions, even the most visceral, are richly social, cultural, and linguistic phenomena” (8). For example, consider that the asbestos in C&D debris may be much less unpleasant to inhale than the scent of a rotten egg but considerably more dangerous to someone’s health.

Handling waste (toxicity & non-toxicity, healthy & hazardous)

Julie identified that the school’s ethos towards sustainability is driven by two main concerns. The first is the more obvious environmental aspect of it, as the various material obtaining and disposal processes are scrutinised in terms of their impact on the earth and the ease with which one can dispose of it after it has been used. The second aspect, non-toxicity, relates to ideas of the health and safety of the students and provides an additional dimension to sustainability. In addition to making sure that the materials the school uses in construction are produced “ethically”, there is also a concern about how those materials will in turn affect the wellbeing of the people inhabiting these buildings, centring the argument for the need for sustainability around a lived, human, experience.

This toxic/non-toxic distinction was also present in our conversation with Scott, Mike, Ryan and Steven as we spoke about hazardous (or in other words toxic) materials. There was an apparent need for the Davis Center project to create a “healthy” environment, both in terms of the physical building being non-toxic, and also taking into consideration the experience of the people who would be using and inhabiting the building. One way that this “healthiness” is proposed to be achieved is through the policing and avoidance of “hazardous” materials.

This sentiment was expressed by Mike as we spoke about why LBC aligned more with Williams’ sustainability efforts:

“One of the petals is healthy building materials … that is thinking about the health of the workers, the health of the occupants of the building [and] the health of the planet. And so that is nice to be people-centred and human or earth and environment centred as well.” Scott reiterated this human-centred approach to sustainability, praising LBC because “it takes a very human approach to sustainability and construction.”

View of Davis Center site from the Williams livestream on the day we visited (11/4/22)

Gravel from crushed concrete at Richard’s MRF (Pownal, VT)

Takeaways

First, we noticed that there was something of a “bottom-up” system of C&D waste management at Williams. That is to say, most of the specific directions for this waste stream were formulated and communicated by organizations and college employees below the executive level (i.e. board of trustees, president of the college). This trend got more pronounced for non-capital (less expensive) projects. While executive Williams groups gave a lot of guidance on sustainable building practices like what materials to use, and general waste production was self-reported by waste haulers, there were no guidelines for the disposal or handling of C&D waste. We got this impression from our interviews as well as the Sustainable Building Guidelines on the Williams College website.

Second, multiple interviewees framed sustainable C&D practices in capitalistic terms. As shown above, the handling of C&D waste was largely dependent on the cost of the project producing it and the team paid to handle it. Furthermore, Scott spoke about the importance of C&D employees “buying in” to sustainable building initiatives and guidelines. In a similar vein, Richard framed WasteExpo (a place for product display & promotion) as an important space for communicating and connecting with others in the waste industry, particularly on the subject of waste diversion. However, a lot of this was underlined by very explicit concern for the members of the Williams College community who would be interacting in and with these structures. Each person we spoke to was first concerned for how their work would affect their communities and the people around them, and then thinking about how these efforts could make the least negative impact on the environment.