Silver, Sludge, and Scraps: Art Waste at Williams College

Jackson Small and Martha Carlson

Introduction

The goal of our project was to explore the various streams of art waste at Williams College in an effort to figure out value of creative production and art-making versus its byproducts. We investigated three distinct artistic practices, photo development, printmaking, and oil painting, and the waste that each class produces. We interviewed professors, students, and other Williams College staff members to gather information about how waste is produced, how it is dealt with, and where it goes at leaving the college’s campus. Our project seeks to show the methods by which art waste in disposed of by the college, and to hopefully elucidate the value of materials left over after creation is finished by asking the question: what is art waste?

Drawing Studio and General Department Waste

Professor Frank Jackson, currently teaching ARTS 100 Beginning Drawing, described several avenues for materials leftover from studio classes at the college. He explains that in Beginning Drawing, “approximately half the class keeps leftover supplies, the unused supplies are kept as back-up for future classes, and used material, like opened charcoal, etc., is often collected and donated to local schools.” Some materials, such as the newsprint used in the print lab, are also transferred for use in other classes in the art building.

What about the material that simply can no longer be used?

Studio coordinator Megan Mazza , “Facilities take care of our regular recycling which usually contains a large amount of cardboard. We tend to reuse much of the cardboard for art projects when we can but anything left over gets recycled…When we have special items requiring special disposal, we usually reach out to Frank Pekarski (Manager of Safety and Environmental Compliance) or Heather Main (Environmental Project Specialist) for their expertise.”

Photo Lab

The Williams College photo lab may not be a space that many people may have heard of. Tucked into a back corner of the first floor of Spencer Art Building, the photo lab consists mainly of what is called a dark room, a small closet sized area where students can develop their film. Inside of the photo lab is a metal sink basin, a small work station, and various other equipment for developing film. The developing process involves certain chemicals to help make the photo appear on the film. The chemicals are generally non-toxic, although they will cause irritation if they come into contact with your skin, so students are encouraged to wash their hands as much as possible.

A step-by-step outline of the development process

One photography student, who requested to remain anonymous, described the process. She mentions a chemical called Photoflow, which seals the film so that there are no water spots on the finished product. She says that the recommended amount is 12 milliliters for one roll of film, and that students are asked to discard any excess Photoflow after they are finished developing the film, which can be dumped directly down the drain. Other chemicals used during the developing process, such as the Hypo-Clear, and the Fixer, can be returned to the bottle after the student is finished with them. “I think we return it to the bottle to save product,” the student said “but not as a precautionary measure of making sure they don’t go down the drain.”

Chemicals used during the development process

After the process of developing film is completed, there is the issue of dealing with the detritus. The student explained that two of the most common “means of excretion” are empty film rolls, and photo negatives. According to her, the empty film rolls can be deposited in the recycling bin, while the photo negatives are placed in a special trash can in the dark room. “…there’s a specific trash can we put the negatives in,” she says, “Maybe because they are saturated with chemicals?” The student claims that she wasn’t informed about where these excretion products go after she deposits them in the designated receptacles. “I have no idea. It’s interesting that we weren’t informed.” This student’s experience with the waste produced in the photo lab begs an important question: should the student body be better informed, or more involved, in where the waste they produce actually goes?

Work station in the dark room

Despite this, the student claims that most materials in the photo lab can be reused. “When we go to develop, all of the developing material, like the container you put it in, is reusable. You just rinse it off with water.” She explains that most students prefer taking their negatives with them, instead of placing them in the designated trash can; of course this is not the case for all students, but the student herself “wants to keep them because these are all things that I think we would want to take with us.”

Heather Main, Williams College Environmental Project Specialist, helped shed some light on another source of waste produced in the darkroom: silver. Since 2001, Williams College has been working with company Evolve to help dispose of the silver on a yearly basis. The process involves an Evolve person inspecting the buckets that receive darkroom liquid, checking the filter cartridge in which the silver gets captured, replacing the filter when it has reached capacity or letting it remain if it has not, and taking away the “minuscule amount” of captured silver. On Evolve, Main said, “They don’t cost us a fortune because they, in turn, get to sell the recovered silver as a commodity.” Post-silver capture that has passed through the filter will go down the drain, and eventually to the Williamstown Wastewater Treatment Plant for refinement.

Print Lab

The printmaking studio at the college is a meticulously organized space. Everything from tools to areas of the room to waste bins is labeled to make absolutely clear what is meant to be used where and for what purpose–as well as more specifically, how to clean it.

Signs above a work station in the print lab explaining how to properly clean and store ink tubes

The studio is non-toxic, but after speaking with a few students in Professor Alyssa Phoebus Mumtaz’s ARTS 235: Intaglio Printmaking class, it became clear that there are still a few things that students are told should not get on their hands. Intaglio printmaking involves etching into or biting into (with acid) a copper plate. There’s a large “acid and corrosive storage” cabinet against the back wall of the studio, as well as a designated sink area for using the acid, although very little acid ends up down the drain. The acid is reused over and over again.

Sink area in the print lab for working with acid

Printmaking technician Javier Robelo is working to find other ways to reuse materials. “What’s interesting about waste in a print shop space is, that…especially in my position, so much of it is finding out ways to reduce it, and…channeling, either extending the life of things or finding new ways to use them.” He went on to describe how scrap paper from trimming printing paper is saved in a bin to use as what are called “paper fingers,” which are used to pick up clean printing paper to protect it from ink.

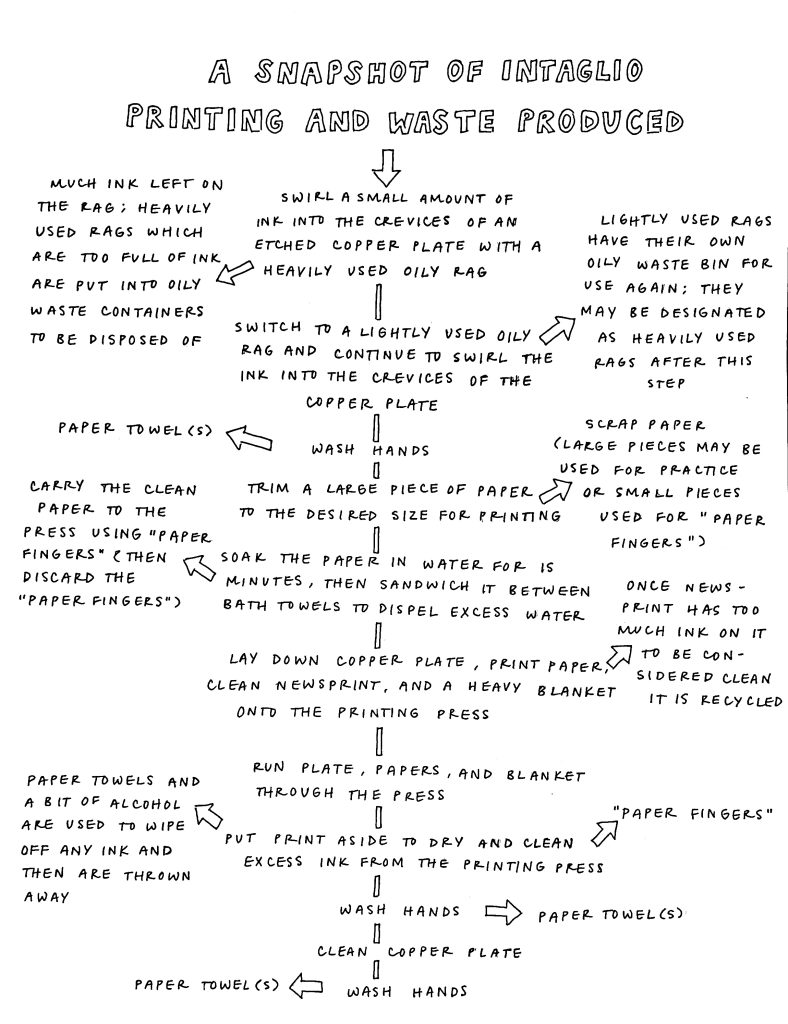

A rough outline of the section of the intaglio printmaking process that I was able to observe and take part in, as well as the various forms of waste produced

The newsprint used during the actual printing is also reused material. Professor Alyssa Mumtaz explained that it’s leftover from drawing classes in the building. She described how there is “a problem with over-ordering at the college [within the art department],” and she and Javier Robelo are working to use “what’s already here.”

Javier also frequently communicates with Heather Main and Frank Pekarski at the college’s waste center (commonly known as the Agway), and he is currently working with them to determine whether the oil-soaked rags that come from the print lab should be handled as hazardous waste. Javier is interested in possibly sending the rags out to be washed and returned but admits that there are limitations that come with being in a remote location such as Williamstown. “You don’t necessarily get access to the same industrial cleaning facilities that you get near an urban space or a city…so it is this question of like, what’s more feasible?”

Oily waste cans for lightly and heavily used rags.

Javier went on to speak more about the move toward non-toxic materials in the printlab. “In the past, intaglio printmaking has been taught using types of things that require a solvent. Now we are using water soluble inks, which you only need water and soap to wash…which just generally makes the space significantly healthier for the individuals printing and for the environment.”

Sign prominently displayed on the print lab wall.

An interesting aspect of art waste, however, is the level of quality that one can produce with certain materials. Regarding inks in printing, Javier explained, “There’s always this question of what can be, you know…what can be achieved with certain inks, against the other ones, but for an educational purpose…we think that this works.”

Oil Painting

The oil painting studio is located on the second floor of the Spencer Art Building. This open classroom with lots of natural light consists of 13 painting stations arranged in a circle. Each student has their own individual workstation, consisting of a small rolling desk, an easel, and a clear plastic palette for paint. In the middle of the circle is a table for communal tubes of paint. Each student is encouraged to take paint as needed, and return the tube to the table when finished. I just find that it produces so much waste at the end of the term,” says Binnie, “I would rather have all the paints in the middle of the room like they are right now.”

Gamblin is the brand of oil paints used in Professor Binnie’s class

Of course, students need an apparatus to paint with. When asked about the disposal of paint brushes, Binnie explained that much of the leftover materials are given to local art programs at the end of the semester: “…anything that’s open but still usable at the end of the term, I donate either to Buxton, or another high school program or just some other arts program that does oil painting.”

Paints are not the only materials that Professor’s Binnie’s class works with on a daily basis. The students regularly use a solvent called Gamsol, an odorless mineral spirit with a low toxicity used for thinning paint. Students also use this solvent to clean their brushes in between uses because Gamsol breaks down the oils in the paint. Each student gets two mason jars per semester to hold their Gamsol. “The pigment that remains in their brush will actually settle to the bottom and then it’ll all be clear so you can actually pour off the clear into your other mason jar,” says Binnie, “So you can kind of have this perpetual recycling process.”

Instruction sheet for how to dispose of solvents and oil paints

There are a few discarded materials in the studio that do need to be handled carefully. The use of Gamsol creates a byproduct that Professor Binnie refers to as “sludge,”which consists of all the paint oils that separate from the solvent and collect at the bottom of the jar. At the end of the semester, the sludge from the mason jars has to be deposited in the “sludge bucket” at the back of the art studio. Professor Frank Jackson explains that solvents in any kind of paint cannot be poured down the drain and are collected in catch basins. Whatever oil/solvent waste that is generated is collected in safety barrels, and picked up periodically, though I don’t know the exact schedule of that,” says Jackson, “as I said, it could be once a semester, or once a year, I just don’t know.”

“Sludge Bucket” in oil painting studio where the Gamsol and paint mixture is deposited

Professor Binnie is always thinking about how to make his classroom more sustainable, from reusable rags to conserving paint. However, a commitment to sustainability in the classroom opens the door for larger discussions on the value of historic art practices. Oil painting is a time-honored artistic tradition with continued relevance, but at a cost. In adhering to the historic practices, those working with oil paints will encounter some level of toxins contained within these “sacred materials.” As previously mentioned, the disposal of oil paints necessitates careful planning and attention, as opposed to other paints such as acrylic. However, by eliminating these materials from the classroom, the authenticity of the experience of oil painting would be lost. “What are you able to sacrifice versus what people expect from a painting class because people want to come and partake in this historic tradition that involves historic pigments?” says Binnie, on the topic. Binnie’s meditations on the value of oil painting versus the waste it produces calls attention to a new understanding within the art community of attention to sustainability, and allows artists to ask important questions about whether or not this sacrifices the authenticity of the medium in question.

Final Thoughts

During our investigation into art waste at Williams College, we realized that this type of refuse has its own distinct characteristics. By examining these several different artistic practices, and observing the waste that each produces, we were able to see that there is much overlap in how the college disposes of its art waste. Our investigation helped us gain a better understanding of how to think about what we define as the byproducts of making art. Art waste has a high potential for reuse, something that we found out while conducting our research. In this sense, what constitutes waste in an art context is very ambiguous. Paint not used on one canvas can be used on another, dirty rags can be reused until they are absolutely tattered, bits of paper trimmed off in art making processes can be reworked as scrap paper, etc. Although these avenues for creative reuse do exist, there are some materials that do have to be carefully disposed of after a single use, making the definition of art waste all the more complex. There is no right or wrong answer to what is represented in the use of the term art waste, just various arguments to be made about how much value to place of the byproducts of art creation at Williams College.