The Waste Stream of Lab Animals

By Amaya Smith and Sebastian Job

Introduction

We examined the waste streams produced by animal experimentation in the science department at Williams College because we were interested in the ethical and moral dilemma of working with living beings that are raised to be experimented on and then killed. We wanted to understand the route that mice, which are the main vertebrates, and flies, the main invertebrates experimented on at the college, take to get to campus. Where do they go after the science department no longer has use for them? We interviewed one student (Shania) who experiments on mice as a resident assistant in the Neuropsychology department, a professor who conducts research on Drosophila (fruit flies), and the Science Center Manager and Safety Officer who oversees much of the department and experimentation.

In our pursuit to discover the waste streams of mice and flies, we discovered that there were strict access rules and secrecy surrounding the vertebrate animal colony. We were denied interviews from a number of sources because they did not feel comfortable disclosing information to students who were not directly involved in animal experimentation. Part of the reason we do not have any original pictures in this site is because we were not given permission to look at the animal colony which holds the eventual waste product, the mice. Nonetheless, through the discussions and interviews held, we learned how at nearly every stage of the animals life, as dictated by their usage, there was an opportunity to produce waste. We were surprised to learn that it was not as simple as experimentation and then disposal, but rather was a complex network that had the opportunity to produce waste every step of the way. The format of the page consists of two flow charts, one for flies and one for mice, as they followed different paths arriving to and leaving campus. We have compiled specific quotations of interest and organized them via the generalized steps of acquisition, raising/breeding, experimentation, and disposal. The organization of the sections illustrate common areas where waste was generated throughout the study as detailed by our interlocutors. Finally there is a conclusion that addresses limitations of our study and attempts to answer the question: Is this practice wasteful?

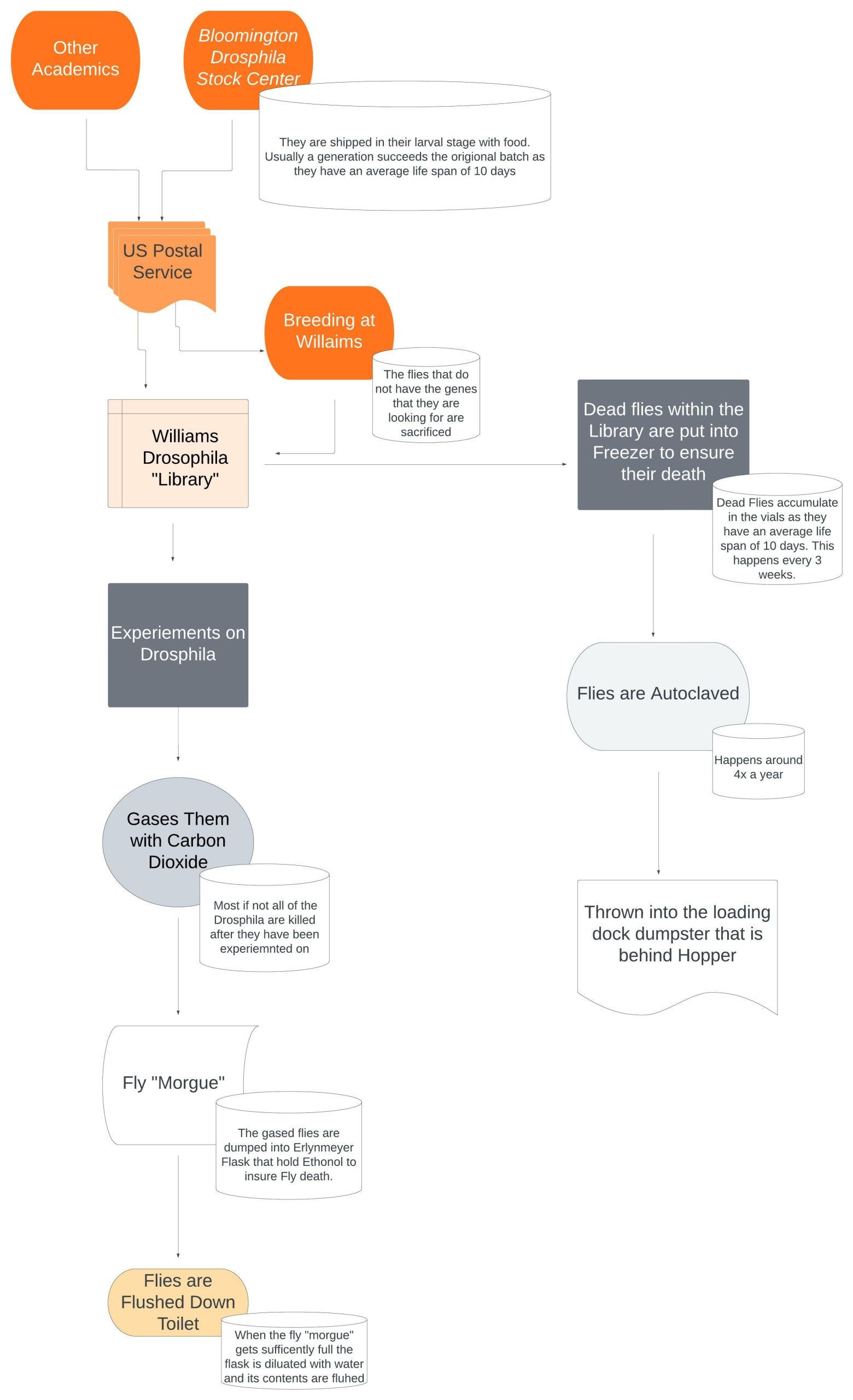

Waste Stream Flow Chart for Fruit Flies

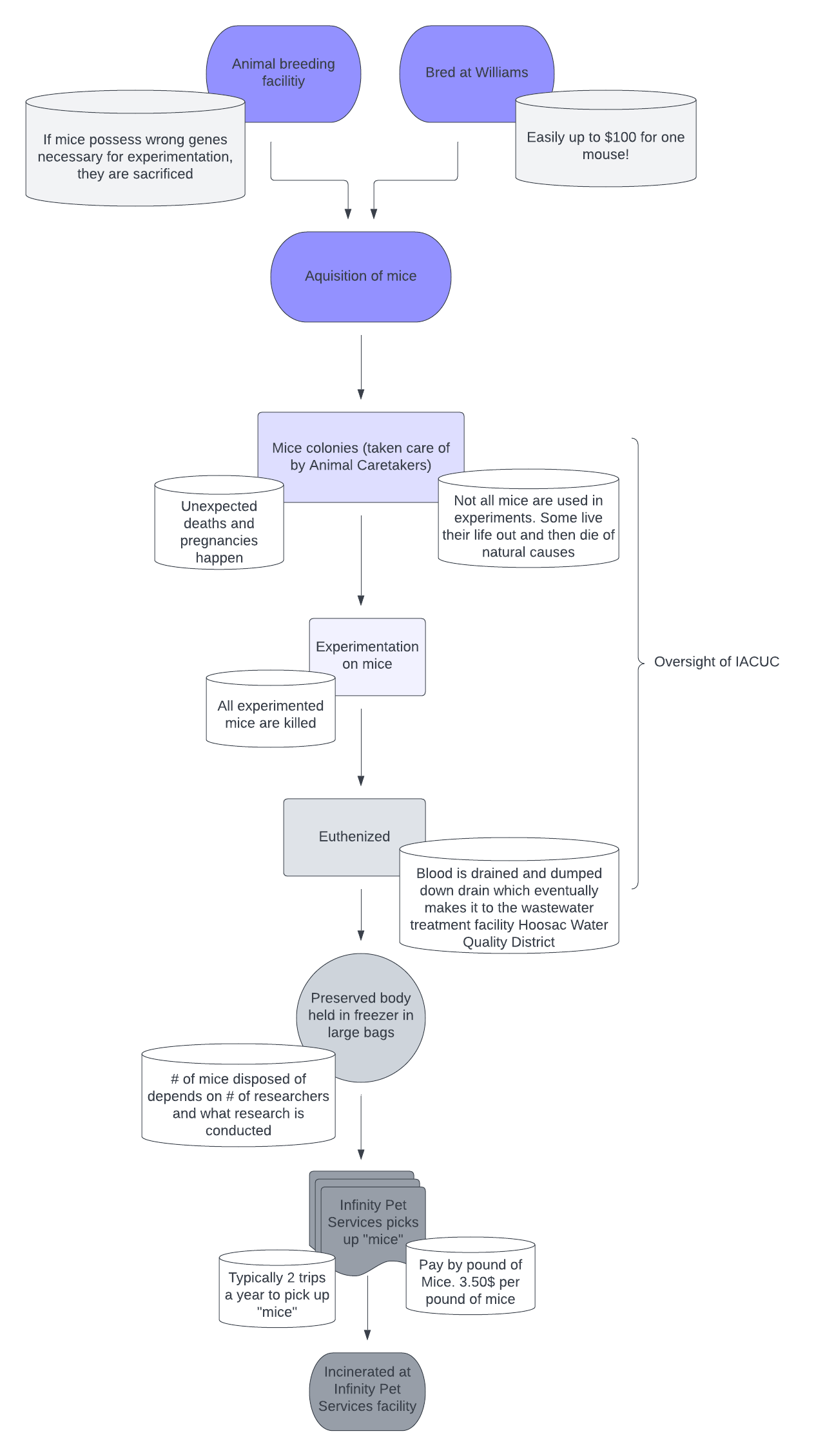

Waste Stream Flow Chart for Mice

Acquiring

The first step of understanding the lab animal waste stream is to look at where it starts before it is considered waste. The Williams College Science department gets their mice from facilities in New England that can breed them in a more controlled and careful way than the college can. They purchase the mice based on the genes needed for that particular experiment. The fruit flies used in the fly experimentation are bought from Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center which was likened to the experience of picking up books from a library.

When asking how much do the mice usually cost the Science Center Manager responded; “You could easily spend 100 dollars on a single mouse. A hundred dollars on a single mouse…You can easily spend that much. It depends on the animal and what trait it’s being bred for.” – Norm Bell

On the acquisition of flies: “So basically, I can call or email the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center and say, ‘Hey, I would like this, this, this, and this.’ So it’s like going to the library and picking up books. It’s literally that simple. And then in the mail, through the US Postal Service, I get a little box with little vials with cornmeal and food and fruit flies, and then they grow and they’re shipped through the mail.” – Biology Professor who oversaw fly experimentation

Raising and Breeding

Once the science center has the animals, they are usually bred within the facility. Many times scientists are searching and breeding for specific genes for an experiment. When the animals are bred but do not have the right genes, they are usually killed as they only have so much room within the science department for animals.

The Science Center Manager shared how they get most of the mice that they experiment on: “Most of our research does not require that level of care (compared to that of what a mouse breeding facility could give) so we breed mice in the (Williams) facility. We are careful about that, we cross them in a certain way so that they are still the same type of mouse, we can buy it from a facility and breed it once it gets here. That is mostly what we do. There are discussions in IACUC about how often we breed them, how many animals we have at any given time, what we do with unwanted animals… you know how many animals we are using in research. So you know, all of these questions are asked in the beginning of the study. [We need to know] all of the animals we need to have to make it a robust study so that we can publish it, that is kinda our goal.” – Norm Bell

On how the process of breeding flies can be self-regenerative and sustaining: “But the really important thing for the stocks is… it’s the fact that they’re the ones that they’re mating and reproducing and then producing their progeny on the plate. So those are the ones who are probably going to see the next generation. And that’s what I keep alive for generation and generation in these little vials.” – Professor who oversaw experimentation on flies

“We have our own breeder mice. Sometimes if we need a litter, I don’t know it is called a litter for mice, but if we need some baby mice for a new experiment, we put a male and a female together in a cage and they breed. If we need hybrid mice, the cross between the 1-29-S1 and the black 6 we breed them together and make hybrid mice. We observe them and their behavior and phenotype. We also see what genes the mice have and we do genotyping. We take samples from their fur and take a punch out of their ear, we pierce their ear and take a skin sample that we send to a genotyping facility. They tell us what genes they have because sometimes we need certain genes for certain experiments.” – Shania

Experimenting

Scientist handling mouse

Williams works with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) to make sure that the process leading up to and the experiments are abiding by ethical rules of animal experimentation. Only Vertebrate experimentation is monitored by IACUC. Invertebrate experimentation is less (or not at all) monitored compared to vertebrate experimentation which provides insight into how the type of animal informs its value and worthiness to live.

“The flies are very different from the mice, we have an IACUC committee here, the institutional animal care committee composed of faculty who work with animals. We have a consultant veterinarian, we have a person from the community and then there are two people within the college who are not associated with this, so I sit in on that, I don’t have a say but I sit in on it as a representative of the science center, and someone in the administrative that sits in and represents the college. IACUC is specifically for vertebrates only; it includes fish, frogs, birds, and any animal work that is done off campus. In the spring they collect tadpoles, they have to submit an IACUC proposal: how do we collect them safely and humanely and what do we do with the animals when we are done with them. Flies are not vertebrates; there are not many guardrails working with invertebrates. Works with leashes but they eat snails, we raise both leeches and snails. Again and because they are not a vertebrate, and this is a decision that was made at a higher level, and may not be biologically sound thinking, but the tendency is to think of them as lower animals who we don’t have to worry about as much, and that is one of some debate.”- Norm Bell

The Biology Professor who oversaw experimentation on flies spoke on why it is easier to experiment with flies compared to mice or other invertebrates: “I mean, so there’s less oversight with flies[in comparison to mice work]… How do you balance the loss of life or suffering if you’re particularly trying to understand pain or some pathologies?”

Disposal

Autoclaving

Eventually, the animals were unsettlingly classified as a waste product. Once experimented on, these animals are almost always killed. The mice’s lives were described as only being useful in experimentation. Therefore, as its use value ends, so does its life. This classification was even visible in the mice’s titles; the scientists describe the white mice as 1-29-S1 and the black ones as Black 6 to differentiate the strain of mouse, and what they are best to be used for.

Many times the killing of the animals was described as ‘sacrificing’. It is the preferred term among scientists because it signifies that their lives were put to an equally or more important use. However, we thought it was interesting that such terminology was also used to describe killing animals that had not been experimented on.

“At the end of use, you know the animals can live for a while and sometimes they are bred and they live their lives in the facility and they may live for some period of time and never get used and then they get..(Long pause) sacrificed at some point. There are protocols for determining when and how that happens. It is all done humanely and euthanized and stuff like that. Then they go into the freezer. Once they are in the freezer they accumulate in there for some period of time until the freezer starts to fill up, and we have a facility that we send them out to for incineration. That is done once or twice a year, something like that, it is not very frequent. It is actually the same facility they send pets to get cremated.” – Norm Bell

“ So disposing of flies, we have this thing called a fly morgue… it’s essentially an erlenmeyer flask… we knock them out with CO2 gas. So we make a selection and the ones that we don’t use… and they fall down into the ethanol. And so they were already asleep when we knocked them out with CO2 and now they’re essentially drowned… It’s probably like tens of thousands of flies. But when this gets to a big jar of dead flies, essentially what I do is I fill it up with water and then we dispose of it by flushing it down the toilet, basically, because it’s all just organic matter… If there are old bottles that are no longer generating flies and things like that, we have a very specific procedure of putting them in these big plastic bags. I freeze them first just to make sure that everybody croaks… I think it’s every three weeks we are culling a bunch of old bottles and old vials. So those go in the freezer first to kind of kill any living flies that are left, and then we autoclave and then throw it in the dumpster.” – Professor who oversaw the experimentation of flies

Conclusion

As mentioned in the introduction, our studies faced a serious challenge in who was willing to discuss their experimentation with us. We did not anticipate the strange secrecy and gatekeeping that became a hallmark of our ethnographic research. The language that our interlocutors used was also very interesting. Most framed the killing of animals as “sacrifice,” which suggests how they view their work as a necessary evil. To have trustworthy results, one needs a large sample size, which necessarily dictates, in the case of experimentation on animals, a large loss of life. Yet in attempting to determine if this practice was wasteful, we found ourselves missing key information. For example, none of our interlocutors were able to provide us with specific, concrete numbers for the amount of waste produced in their field. Nobody who was willing to talk with us could give us rough estimates on the number of animals tested, or even the number within the animal colony at the time. In this regard, it is difficult to ascertain the extent to which this practice was wasteful, as if we accept the experimentation and killing of animals as a necessary evil, then naturally the question becomes: Do we need to kill as many as we do? Yet, we were unable to learn how many are killed, besides the vague quantity of “a lot.” To an extent, we must therefore be reliant upon the college and the IACUC, which oversees the use of vertebrate animals in experimentation, in determining the utility and ethics of such experimentation. So then, is experimentation on animals a wasteful practice? If you view such research as innately cruel and unjust, then definitely. If you view this experimentation as necessary for furthering the human condition, so long as experimentation is not performed unnecessarily, then we have not accessed enough data to answer. This is where we land.