Exploring the Food Waste Stream at Williams College

by Sabrina Churchwell and Maya Goldstein

“We’re [Williams College is] one little stop along the whole stream and, there’s a lot of people other than us, [who] either aren’t getting enough [food] or are being impacted by the waste and overconsumption or just our consumption [as Williams College] in general. How can we mitigate the impacts of our own consumption?” – Bekah Lindsay

We investigated the food waste stream at Williams College, with specific focus on Whitman’s Dining Hall. We gathered our information from multiple sources including: dining staff members, students involved in waste management, and multiple people involved in processing food waste once it leaves the dining halls. We had hoped to have a conversation with the head of dining at Williams College, but unfortunately due to scheduling, he was unable to meet with us.

Before we share our investigation’s findings, we wanted to acknowledge the incredible work being done by the dining staff workers and share our admiration for their hard work that keeps Williams students happy and nourished. The staff works tirelessly to ensure that students on campus have constant, delicious, and healthy food served with a smile and a good conversation!

Food Waste in the Whitman’s Kitchen

Through interviews with multiple Whitman’s staff members, we have concluded that there is a plethora of food waste & non-food waste streams that are generated in the kitchen. Food is wasted through a variety of ways in the process of cooking and food preparation. Our sources estimated that approximately 20lbs – 30lbs of food are wasted per meal (i.e. breakfast, lunch, and dinner.) That is a substantial amount of food waste!

Before being able to create solutions to reduce waste at the college, it is critical to be aware of the factors that are leading to excessive food waste. One source stressed the importance of being mindful while cooking and paying attention to the dishes at hand, as it is common to throw away food that has been over-cooked, burnt, or simply does not taste good. However, most of the food waste occurs at the end of mealtimes when the dining halls closes.

One source commented, “We are not allowed to reheat anything that is on the line after dining closes, so we have to throw everything away. Once it is on the line and students are touching it, we cannot use it again or reheat it.” This applies to all the fruit placed in baskets in the dining hall as well. Once the fruit is up for grabs, whatever remains unclaimed when dining closes must be thrown away due to risk of potential cross contamination. Imagine having to throw away countless perfectly good apples, oranges, and bananas just because they have been exposed to students. It is partially due to this policy that fruit and produce are some of the highest wasted food items in dining.

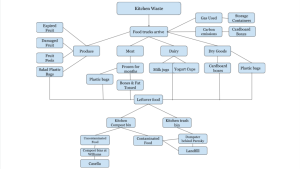

Our second interview subject commented, “There is so much waste, especially with the fruit. Most of the waste is just food, but there is also a lot of plastic and cups that get used and thrown away.” It is important to expand the scope of our research to encapsulate non-food waste produced in the kitchen, as well. The flow chart below reflects various non-food waste streams, such as plastic wrappers, cardboard boxes, storage containers, milk jugs, and yogurt cups that are all produced as a result of food preparation.

Food Waste by Students

The Sustainable Living Community is currently piloting a program of dorm kitchen composting run completely by students. Last year, upperclassmen dorms had composting that was picked up weekly by facilities. Unfortunately, that budget was not renewed for the 2022-2023 school year. So, students have taken matters into their own hands. The Sustainable Living Community members used money from the Residential Life Teams budget to purchase bins for all upperclassmen dorms. Weekly, volunteers go into each of the dorms and collect the compost. Of course, this is only a short-term solution. The goal of the student run composting is to provide data to the College that composting in upperclassmen dorms is not only worth it, but members of the SLC believe it may bring to light the fact that the college is violating the Massachusetts law, which was recently amended in November 2022. The law is a called the Commercial Food Material Disposal Ban, and it “bans the disposal of food and other organic wastes from businesses and institutions that generate more than one-half ton of these materials per week.” (Mass Gov)

We asked a handful of students how they felt about their relationship with their own food waste at Williams.

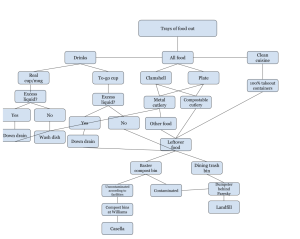

Jared Stiller, a sophomore at Williams College sat down with us to talk about his relationship with food waste at school. He said, “I feel that the likelihood of wasting food at Driscoll or Mission is substantially lower than at Whitman’s because you can return to get seconds if you want. Since at Whitman’s you are not allowed to go back in to get more food after your first plate, you load up your plate with too much food then end up throwing half away. The stomach is always bigger than the eyes.” Additionally, he commented that there is some general confusion about appropriate locations to compost food in the Whitman’s dining hall. He sited specifically the conveyor belt set up to leave dirty dishes and the unlabeled holes wherein students dispose of food. Are these receptacles for organic material only, or can non-food items be thrown there as well? The lack of clarity and proper labels inherently produces more waste while potentially jeopardizing the ability to compost successfully.

Jared Stiller, a sophomore at Williams College sat down with us to talk about his relationship with food waste at school. He said, “I feel that the likelihood of wasting food at Driscoll or Mission is substantially lower than at Whitman’s because you can return to get seconds if you want. Since at Whitman’s you are not allowed to go back in to get more food after your first plate, you load up your plate with too much food then end up throwing half away. The stomach is always bigger than the eyes.” Additionally, he commented that there is some general confusion about appropriate locations to compost food in the Whitman’s dining hall. He sited specifically the conveyor belt set up to leave dirty dishes and the unlabeled holes wherein students dispose of food. Are these receptacles for organic material only, or can non-food items be thrown there as well? The lack of clarity and proper labels inherently produces more waste while potentially jeopardizing the ability to compost successfully.

On the left you can see the individual compostable utensils Stanger refers to.

Emily Stanger had similar thoughts to Jared. She said “I think it is annoying because you can only go in there [Whitmans Dining Hall] once and so I either don’t get enough food because I don’t want to get too much and not eat it or I get too much because I don’t want to be hungry and then I throw it out.” She also said “it is better now that they are giving out compostable forks and knives separately but before when they gave the packet of fork/spoon/knife/napkin I would really just use one utensil and compost the rest.”

Nina Yankovic looked to solve the problems she saw in the waste in dining, proposing “Snar [Williams College late night snack bar] could have leftovers from dinner as a healthier option for people who missed dinner.”

Lauren Ryan also has troubles portioning, saying that it is hard to know what she thinks will taste good, so she takes a lot of options knowing that she will not eat everything. And, because she cannot go in another time, she takes full portions of each option.

Alternative Ways of Handling the Waste at Williams: WRAPS

One of the ways that Williams students work to minimize the waste stream produced by dining is through the club WRAPS. It stands for Williams Recovery of All Perishable Surplus, and they take food that was not consumed by students (the food mainly comes from Whitman’s Dining Hall), repackage the food, and bring it to local community organizations including Lewis House, Roots Teen Center, and YMCA North Adams.

We spoke with the club’s co-president, Bekah Lindsay. Lindsay is a sophomore at Williams, with a special interest in food justice. Bekah discussed the slight conundrum that she faces in her role. Her main role, as president of WRAPS, means that weekly she and a group of 5-7 other students repackage untouched trays of dining hall foods (as per ServSafe regulations) into meal containers. The dining staff put Those meals get frozen and delivered to partners around the community: Lewis House, the Wayfair Call Center, Mohawk Forests, and the Root Teen Center. She and the WRAPS organization has to navigate the push and pull of wanting to have food to give to local community groups, yet also understanding that this is ‘waste’ produced by dining, and ideally it shouldn’t exist in the first place.

Lindsay specifically highlighted this dilemma when she told me about the Lewis House, requesting that I keep an eye out for potential partners for them in case I come across any during my research. She said that the Lewis House unfortunately “somebody who used to help them procure a lot of meals dropped.” Which means they are now down 150 meals each week compared to previous weeks.

Lindsay also highlighted the flaws in her own organization–she said “one of the other things that we have to think about is how are we [as WRAPS] contributing the waste streams additionally.” One of the things she is thinking about when she says this is that the containers that they package the meals. They cannot be reusable because, as Lindsay says “those are just too hard to get back,” and they cannot be compostable, as they have to be able to hold up in the freezer for up to a month.

The Composting and Trash Process

Our investigation yielded concerning information regarding the composting process that occurs in Whitman’s dining hall. After speaking with multiple people who work in the dining hall, we learned that the composting process is not nearly as successful as it could be. One source said that the composting process “does not work at all,” while another source said, “it is maybe 50% successful, or even less”.

When asked if the current composting system is successful, one subject responded, “Not really. Maybe like 50% successful. I think the composting people come twice a week and they take 6-7 large containers of compost. But if it weighs more than 30 lbs per container they won’t take it. People also mix everything in with the compost, so then the entire bag has to be thrown away.”

In response to the same question, another subject commented, “If I could change anything about the dining process it would be that the workers respect the composting procedure. No one cares so the composting doesn’t work. We don’t really do it. Everyone throws everything in together. It is not kept separate like it should be. They throw the gloves and plastic and the clamshells all together with the food. It all gets thrown into one big dumpster. I’ve seen it. Do you think someone is going to sort through all that and pick out the stuff? No. They need to improve the system so it works.”

It appears the main explanation for the inefficiency of this process is a result of general negligence for the conduct required for proper composting. Our sources confirmed that a lot of non-food materials get tossed into designated composting bins, resulting in contaminated loads that cannot be processed by the company responsible for handling Williams’s waste.

“Oh, I love everything about the garbage business.I love the people. I love the customers. It’s a universal thing. I could have a customer on the line that was a CEO of a company. And then the next one was a struggling resident needing to have help to pay their bill. It’s just like this universal thing. And I liked the variety of it. I love the tangible impact of recycling, I love seeing the bales of cardboard being pulled out and bailed and set off to market. I love the truck equipment aspect of it. I’m still a truck driver and excavator operator at heart… I love the employees too. Insofar as they were some of the hardest working people out there that are driven by more than a paycheck for sure because if you want to be a truck driver, you can certainly pick a lot cleaner of a job than that.” – Trevor Mance“

Once food waste leaves Williams’ campus, its journey is far from over. The waste travels to Bennington, Vermont, at Casella’s composting facility where it breaks down for months. The food is placed in large mounds and then is processed at a high temperature for approximately three weeks, allowing its transformation into material that is sterile and pathogen free – the perfect fertilizer for gardens and parks.

Aerobic composting is the technique that Casella’s Bennington facility uses. This is a process of mixing the correct proportions of carbon (“the browns” and nitrogen (“the greens”), and providing the right amount of oxygen so that the natural bacterias and microbes eat and convert the solid organic material into soil, by breaking down the molecular bonds. As Trevor Mance explained in regards to his facility, “there’s no chemical additive, there’s nothing fancy. It’s just giving them that perfect environment.”

“It’s an industry that you never choose. But once you’re in it, you never leave it.”

-Trevor Mance

Proposed Solutions

Food waste is an international problem, yet in order to enact positive change and reduce food waste, we must begin the work in our local communities. With the help of our community members and the Williams administration, we can take great strides in living more sustainability as a college. As a result of our investigation, we have created a list of proposed solutions to combat food waste at Williams College.

- Abolishing the one-swipe policy in Whitman’s kitchen.

- Allowing dining staff to take left over food home after meals.

- Replacing the clamshell containers with reusable vegware or plastic alternatives.

- Expanding the WRAPS program to all three dining halls on campus.

- Bolstering the awareness surrounding the composting process and reinforcing its importance to students and staff.

The Unity of Garbage

Liker Mance’s quote above, we wanted to conclude by saying a few words about the unity of garbage. We are all implicated in the process of waste production, yet only some of us have to deal with its management. First, it is important to acknowledge with deep gratitude all the workers who are involved in this field and the composting process. As we can imagine (and have begun to understand through our field trips in our Waste & Value class), it can be a very grueling and challenging line of work that most people have little exposure to.

Everyone and everything on the planet plays a role in food waste–whether that be on the production side, the processing, or the post-consumer side. Yet, only a select number of us actually have to deal with managing it.

Let’s destigmatize waste management. Take ownership of the amount of waste you produce, and don’t be ashamed. Understand its impact, and try to minimize your future waste. We are not perfect, nor will we ever be. As we strive towards more minimal-waste lifestyles, it is important to be intentional about the policies and practices we use each and every day.

After all, garbage ties the world together.