When our translator impressed upon us that Nishiki Weaving represents the pinnacle of weaving not only in Japan but also in the world, I couldn’t imagine what makes it so special, and I wasn’t sure what to expect from our tour. But after seeing the textiles and talking with various people involved in the process of creating a Nishiki textile, I now have a much better sense of what makes Nishiki a class of its own, similar to but also far elevated above brocade.

After walking into the gallery of the Nishiki Koho Tatsumura Company, I found myself captivated by hanging textiles on display. As I moved forward and backward and from side to side in front of them, the light reflected off of them in ways that made the textiles seemed to come to life. The richly colored threads shimmered and seemed to dance with light, and each angle revealed new colors and details. I was amazed by the layers of thread that gave the textiles a 3D appearance. Some of the textiles were fairly abstract, but rather than being inaccessible, this abstraction served to make them mesmerizingly mysterious and multivalent, as if layer upon layer of meaning had been intertwined with the layers of thread.

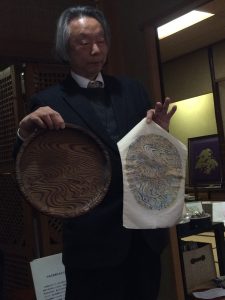

Tatsumura-san also showed us examples of different textures that they’d created to mimic natural patterns and textures in nature. I loved that they drew inspiration from daily life and from nature, and their beautiful textiles made me appreciate those everyday patterns and textures in new ways.

Tatsumura-san, the future successor and 4th generation of the Tatsumura weaving business, explained his company’s philosophy and gave us a tour of the weaving area. Being in the loom room felt like being inside the brain of a 19th century inventor.

I turned in slow circles, trying to get my bearings amidst the layered rows of thread, shelves of shuttles, and the maze of wooden beams that rose up and seemed to intersect at every possible angle above my head, draped by rectangular, wooden ‘punch cards’ with various arrangements of holes. My ears were met by an unfamiliar chorus of sounds coming from one of the looms that was being operated – the creaking of the wooden pedals, the rattling of the punch cards moving above the loom in a big loop, and the soft thumping of the wooden block pressing each newly woven thread into the fabric.

With the help of Tatsumura-san’s explanations, I began to orient myself and get a better sense of how these Jacquard Looms worked, but I still had a hard time wrapping my head around it. After our tour, however, Tatsumura-san let each of us try weaving on one of the most simple looms, and the hands-on experience really helped me understand the whole process a lot better, in particular the shuttle works and how the warp and weft come together. After I’d gotten into the rhythm – press the right pedal, pass the shuttle under the raised warp (vertical thread), pull the weft (horizontal) tight, release the pedal, tap in the thread, press the left pedal, pass the shuttle through, etc -, it was a surprisingly soothing experience. It was also very gratifying to watch the little piece of fabric in front of me grow slightly longer with each pass of the shuttle until I had created a small fabric sample that I could take home.

While others were taking their turns on the looms, we watched a video that also helped explain the weaving process. One thing that fascinated me was the way in which gold (or silver) is added to the textiles. Gold leaf is applied to washi paper that is then stacked and cut into extremely thin strips (about .6mm thick). These paper strips can then be woven into the textile directly or wrapped around silver thread to make a gold leaf thread. Hearing about this process made me realize how many things I had taken for granted about textiles. I’d admired the gold and silver thread only an hour before, but I hadn’t thought about how it was made; I guess I’d just assumed that it could be dyed that way or something.

My appreciation for the Nishiki textiles only continued to increase over the course of the day, as my understanding of the amount of work and the level of attention that goes into them grew. For example, when I thought about textiles before today, I typically thought about the time intensive process of weaving (i.e. it takes a master 8 hours/day to weave 15 cm of textile), but I didn’t ever think about all of the other steps involved in the process, before weaving can even begin. One such step is pattern making, which is the intermediate step between concept and production. We met with a pattern maker, whose job it is to translate a 2D painting into a 3D woven work of art, and he explained the many steps involved in this line of work, which is so complicated that it took several rounds of explanation, questions, answers, and demonstrations for us to even understand the most basic level of what he does. Knowing how to do it and being able to do it is, of course, an entirely different level of difficulty.

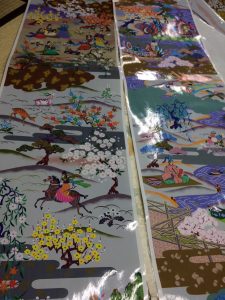

A pattern for an obi without repetition

Essentially, every single intersection between the warp and weft has to be planned and coded. First, the design has to be drawn out on graph paper, with each box receiving a different color, then this is analyzed and translated to a code for the punch cards, with one card representing one line of one color of thread and the holes in the card indicating where the horizontal colored thread needs to go over or under the vertical thread. This gets increasingly complicated with more colors. For example, a textile with 13 colors will need a 13 punch cards (one for each color) for every single row of thread. This means that the pattern unit for a multi-colored textile can easily have 9,000-10,000 punch cards for just a few feet of fabric. If the textile is one without a repeated pattern, it might have as many as 80,000 – 100,000 punch cards. I honestly thought I’d misheard or misunderstood when I first learned this. I’m still trying to wrap my mind around how time and work-intensive the whole process is. Even the process of dying the silk is, as we learned from our visit to two dyers, quite challenging, requiring patience, skilled trial and error, and good color instincts.

Ultimately, the remarkable and perhaps even more mind-boggling fact is that we only got tiny a glimpse of the steps and people involved. From start to finish, more than 70 specialists are involved in the process of making a Nishiki textile. What I found so inspiring about this is the fact that these people are not working for individual glory or fame but for the sake of the technique and the art itself. The person who dyes the silk or cuts the gold leaf into strips might not ever get to see how his/her work is reflected in the finished product, yet he/she believes in it, has the vision to imagine the final product, trusts in the other specialists to take over the next step. These artisans are investing together in a final product, and the result is unparalleled, far beyond something that any one person could achieve alone.