Historical Background of Nishijin Weaving

Since 794 when Emperor Kammu set up Kyoto to be the site of the imperial capital, weavers flocked to be near the imperial palace. Silk weaving was brought over to Japan and Korea by the Hata family, who gained influence from the massive amount of land that they owned. The silk weaving technique was incorporated by the Office of Weaving through which all imperial orders were made.

During the Onin Wars (1467-1477) weavers that worked under the imperial palace and in Kyoto proper fled until the fighting abated and the city could once against be inhabited safely. They returned to set up their shops in Nishijin, a district of Kyoto.

The weaving industry grew to be the largest industry in Kyoto during the Genroku era (1688-1704), but suffered serious setbacks. In the Edo (1615-1868) period, the price of silk yarn rose when overseas trade began to flourish. In the Meiji (1868-1912) period, the capital moved to Tokyo and Kyoto based weavers had to compete. So, Nishijin weavers were sent to France and Austria to advance their own weaving and were introduced to the jacquard power loom that enabled mass production. The long standing history of weaving within Nishijin has made it the center of production for high quality textiles within Japan.

Technical Background

- Warp – The threads on a loom that go over and under. These are the threads that make up the foundation for the woven piece. The weft threads are woven through these threads.

- Weft – The thread that is passed through strands of warp thread in order to weave a design.

- Shuttle – Tool that holds the spool of weft thread in order for weavers to slide the weft through strands of warp threads.

Shuttle with blue weft thread atop a loom. Credit to Trapunto

Jacquard Loom

Developed in France c. 1804, by Joseph-Marie Jacquard, the jacquard loom is an improvement on the original looms & punch card process. The Jacquard loom uses punch cards that designate which strands of the warp must lift in order to slide the shuttle through to create the design. The design is imprinted on punch cards that are read by the loom.

A jacquard loom and its punch cards used by Koho Tatsumura Corp.

Cultural Background

Other than its historical connections, weaving is the primary method of creating traditional Japanese dress. Kimono, obi, and noh costumes are all created through weaving. Wearing these beautifully woven garments were a symbol of status because of how time consuming and expensive they were to make. The patterns on the garments were representative of what was important to the Japanese people. Certain animals, flowers and shapes stood to mean prosperity, long life, peace, love and honesty. Geometric shapes were reserved for ‘manly men’ while softer, more round shapes were reserved for females. A mix between the two could mean a woman who was more masculine, or a man who was more feminine.

A noh costume.

Koho Tatsumura Corp.

Background on Tatsumura

Tatsumura Art Textiles and Koho Tatsumura Corp. are now two separately running companies, but the background of textiles within the Tatsumura family is important to understanding the prestige amongst their works.

Grandfather of current Koho Tatsumura Corp. head Tatsumura Koho, Tatsumura Heizo (1876-1962), worked in currency exchange, his family’s business, until the death of his grandfather when Tatsumura was 16. The business started to go into decline and he decided to go into the textile and kimono industry. He first worked in sales before moving onto becoming an independent kimono manufacturer. By age 30, he had patented two weaving techniques called Takanami-Ori (高浪織) and Koukechi-Ori (纐纈織). With the introduction of the jacquard loom, Tatsumura Heizo saw the possibility for new weaving techniques to be created and his innovation led to the creation of amazing brocade art, whose style was copied by other manufacturers. Tatsumura Heizo’s innovations during this period led to his company’s designs becoming the gold standard for weaving during the time. He also started restoration work of ancient fabrics and textiles that earned him national recognition.

Nishiki Weaving

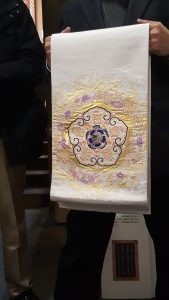

The group met with Tatsumura Amane, the successor to Koho Tatsumura Corp., the pinnacle company in Nishijin weaving that specifically works on the Nishiki technique. Nishiki weaving(錦織 )is weaving done with real gold and silver thread. The silk thread is either wrapped around washi paper laden with sheets of gold foil, or the foil itself is set out by a gold craftsman onto trays and then cut by another craftsman who turns the sheet into strings of gold that are spun into thread. The process is extremely precise because exposure to different elements can change the color of the gold and the color of the gold thread matters just as much as the dyed silk that is used alongside it. Tatsumura Amane and his father have created beautiful pieces of artwork and clothing using Nishiki weaving, bring fame back to this ancient technique.

Obi created by Tatsumura

Golden thread on one of the looms.

Besides their creations, Koho Tatsumura Corp. also works on the reconstruction of ancient textile fragments. In doing so, the fragments are analyzed heavily and research is compiled to understand through what loom and through what technique, using what colors and thread was the original created. The company has involved loom craftsmen within their endeavors to help re-create the looms that made the fragments. Koho Tatsumura Corp. owns re-created looms from both the Nara (710-794) and Heian (794-1185) periods.

Pattern Planning

Tatsumura Amane was kind enough to take the group to visit craftsmen that his company employs when creating a piece. This is called bungyou – a collaborative system for the process of weaving 1 work.

The first part of the weaving process is design and that job goes to the Ozasa Studio. Ozasa and his team work on consultation with the client and preparing a design that fits the vision of what is trying to be woven. That initial design is then painstakingly colored; sometimes using paint to emboss the image and create a more realistic feel to the final product. Once the design is in agreement with the client’s budget for colors and the amount of thread that need to be used, the design is then mapped on much larger pieces of paper. The mapped designed looks akin to graph paper where each line and point on the page corresponds to tracking the use of the colors and the pattern within each line. Afterward, a member of Ozasa’s team works on translating the mapped design to punch cards for the loom to use later. The punch cards keep track of soshiki – where warp and weft threads meet. For one design, whether or not it repeats, can use around 4000 to 40,000 punch cards. There are also 3 types of punch card layouts: 400, 600 and 900. The greater the layouts for the cards, the finer the thread that is being handled. 400 is the basic layout used for Nishijin weaving.

Patterns by Ozasa.

Silk Dyeing

During the visit to Kyoto, Tatsumura Amane introduced the group to the Okamoto Brothers. Two brothers ran this silk dyeing operation that has been in business for more than 150 years. The dyeing process, for them, takes sheer skill and the knowledge of how to mix colors by eyesight rather than through the use of precise measurements.

To start the dyeing process, boil the requested batches of silk yarn to rid the batch of any extra oils or debris. This allows for the colors to stick to the yarn easily once they are dyed. Large bundles of the thread are then dunked into an oil heated vat of dye and constantly rotated using a large metal hanger-like tool. The brothers receive a sample of the color that they need to match from their client and the dyer changes the color of the vat accordingly. Two metal poles protrude over the top of the vat, from one hangs the bundles of silk currently being dyed and the other is used to rest the wet yarn as the dyer squeezes the extra water and dye from the yarn to check how close the color matches the sample. Once the color is achieved, the yarn is coated in fixing agents that prevent the colors from running or changing. Then they are hung to dry for about 1 to 2 days before being wrapped again to send back to the client.

Works Consulted

da Cruz, Frank. “The Jacquard Loom.” Columbia University Computing History. 20 Jan. 2008. <http://www.columbia.edu/cu/computinghistory/jacquard.html>

Junkerman, John, Osamu Kaneko. The Traditional Crafts of Japan. Vol 1., Diamond Inc., Tokyo, 1992.

“Kimono Symbol Meanings.” Hunted and Stuffed. <http://www.huntedandstuffed.com/pages/kimono-symbol-meanings>

“Nishiki: The Beauty of Nishiki.” Textile Fine Arts of Tatsumura Koho. <http://www.koho-nishiki.com/en/about/>

“About Heizo 1st Tatsumura.” Tatsumura Art Textiles. 2006.<https://www.tatsumuraarttextiles.com/about/tatsumura_heizoh.html>

—–

Loom & Shuttle Image Source: https://trapunto.wordpress.com/2010/03/28/weaving-on-my-table-loom/