The idea of the white savior is simple: a white, typically privileged character helps the non-white characters in their struggle and by doing this, he/she becomes a morally enlightened human. Take The Blind Side, for example. Leigh Anne Tuohy (Sandra Bullock) is an white upper class woman, bored with her daily routine as a suburban mother and socialite, who rediscovers meaning in her life when she adopts a homeless black boy, Michael (Quinton Aaron), and helps him succeed as a student and athlete. Or look at The Help, which tells the story of Skeeter (Emma Stone), a girl of the Southern Debutante class, who wishes to pursue her career as a writer, and in doing this, allows the voices of the black housemaids to be heard. These characters are often presented in blaringly obvious ways; Leigh Anne Tuohy is rich and white, Michael Oher is poor and black. But the white savior can exist in subtler forms. Now I will diverge from the mainstream white savior archetype and discuss a more peculiar form, in which the saviors are no longer superior to, but rather identify with those they save.

Whether you have or have not seen Hairspray (2007), you probably associate it with its eccentric costumes, fun songs, and dances, all of which are based on the culture of Baltimore in 1962. The movie tells the story of Tracy Turnblad, an overweight, white, high school girl. Her dream is to dance on the Corny Collins Show, a local TV show that features “nice white kids” who dance and sing to the latest hits. One day, Tracy decides to pursue her dream and audition for the show, but she is rudely rejected by Velma Von Tussle, the snobby manager and mother of the show’s star performer, when she says, “And so my dear, so short and stout, you’ll never be in so we’re kicking you out!”. Right off the bat, the viewer sides with Tracy as the underdog. That same day in detention, Tracy meets and befriends a group of black kids (Seaweed and his friends), who are infatuated by her confidence and stylish dance moves. They tell her, “you one of us” since she fits with their crowd. Seaweed and his friends later face an identical rejection when Von Tussle tells them that Negro Day (the one day per month when they are allowed to perform) is officially over. Tracy and Seaweed (and his friends) have similar struggles, experiences, and dreams to perform on the Corny Collins Show. Though each briefly get the chance to perform, both face discrimination and cannot pursue their dreams because of physical appearance.

Tracy (right) and her best friend, Penny, dance to the Corny Collins Show.

Seaweed and his friends dance in detention.

Given everything I have discussed about this movie so far, (this being very little), it is easy to think that the issue with this particular type of white saviorism requires less attention than the more typical type, since Tracy is depicted as equal to, rather than superior to, the black people. I will tell you why this idea is wrong, but first let me ask this question: to what extent can society’s criticism of bodies (commonly known as fat shaming) be viewed with equal importance as the issues of racism and segregation? This seems especially egregious in Baltimore, a city that still today faces immense racial separation and socioeconomic divides. I cannot imagine putting fat shaming into the same category as segregation and racism, given their historical significance and impact on our nation. The movie, Hairspray (2007) diminishes the importance of the segregation faced by the black characters by comparing them to the problems Tracy faces as an overweight person.

The initial interaction between Tracy and Seaweed and his friends takes place in detention. Tracy enters the room and is immediately taken by the smooth moves of the kids around her. When she joins in, she is warmly received by the group, who all clap after she puts on a little solo. Contrastingly, when Link Larkin, the Corny Collins Show’s lead singer and heartthrob, attempts to join in, he is given the cold shoulder. The movie equates Tracy and the black characters by situating them both in detention, and then reinforces that exclusively Tracy is one of them when Link is outwardly rejected. Following Tracy’s brief fame on the Corny Collins Show, the detention room suddenly transforms into the coolest room on campus. When Penny, Tracy’s friend, appears at the door, Tracy casually says, “She’s with me” the way a rock star would give a friend access to the VIP section. She makes detention, a previously negatively connoted space, a hip place for her new friends to hang out in and feel good about. This scene enforces that Tracy can be compared to the black characters because of their similarities.

After detention lets out, Seaweed and Tracy dance while Link watches.

A similar trend appears later on in the movie. Tracy, in her role as white savior and agent for change suggests “If we can’t dance, let’s march” to Maybelle (Seaweed’s mother). Soon thereafter, a non-violent march processes through the streets of Baltimore. Tracy, with her “Integration Not Segregation” sign in hand, leads the pack until they meet face to face with the Baltimore Police. They cannot proceed, but Tracy will not back down without a fight. When the police officer turns his back on the protesters, Tracy hits him on the back with her sign. The police officer then threatens to “take the whole lot in”, and the scene erupts into violence.

Seaweed, Maybelle, and Tracy lead the march.

Now I am coming closer to making my point. The movie reinforces over again the depiction of Tracy as an ally to the black characters. So, it is believable that Tracy would actively participate in the march, stand at its forefront, and even hit a police officer for a cause she believes in. But in presenting Tracy in this way, Hairspray gives the impression that Tracy, because of her struggles as an “outsider”, truly can identify with the black characters and their struggle with racism. However, this is wrong. She is not an outsider just because she is overweight, even though the movie portrays her as such. The fact that she is white and will never experience what a black person experienced in Baltimore in 1962 brings me to my point that Hairspray trivializes the real struggles that people faced in their fight for civil rights when Tracy, who is also presented as facing social discrimination, effortlessly unites people and creates change for civil rights.

That a march for civil rights could have been led by a teenage girl as easily as Tracy did in the movie, or that protesters could have escaped police arrest and violence as easily as Tracy and others did in this movie, brings me to my next point, which concerns the misrepresentation of Baltimore in the 1960s.

In the “Welcome to The 60s” scene, Tracy drags her hermit mother out of their house for the first time in ten years. To Edna’s surprise, the whole world has changed for the better! The scene is full of vivid colors, action shots, and lots of sparkles. The 1950s did not cater to the plus size woman, but the 1960s do! Edna walks out of a dress shop in a pink sequined dress, a dramatic contrast to the drab clothing she previously wore. The scene implies that the coming decade will bring a new and improved version of everyone and everything. But the song misrepresents the reality of life in Baltimore in the 1960s, and puts an idealized, white washed version on display instead. The Dynamites, three beautiful black female performers, ironically sing, “take your old-fashioned fears, and just throw them away”, and “the future’s got a million roads for you to choose.” In reality, black people had a lot to fear in the coming decade; the Riot of 1968 brought on deeper racial divides, police violence, and anything but “a million roads for you to choose” from. The movie’s representation of Baltimore in the 1960s shows what a white girl might see in her own idealized future, but ignorantly overlooks the fact that this was not at all the case for black people, which is ironic considering the story is supposed to be about racial integration.

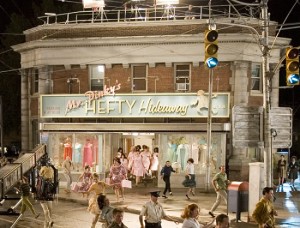

Tracy and her mother, Edna, walk out of Mr. Pinky’s Hefty Hideaway in their new pink sequined dresses.

Performers on the Corny Collins Show are now integrated.

The final scene, “You Can’t Stop The Beat” really hits home my final point. The characters, all different colors and sizes, come together on The Corny Collins Show in the grande finale. Tracy and her black friends have succeeded! But what exactly have they succeeded in? Throughout the movie, Tracy wishes for her own right, and for the right of black people to perform on television, but in obtaining this goal, the group becomes homogenized to the white way of doing things. After performing solo, Little Inez wins “Miss Hairspray”, a traditionally white prize and status. The integrated group of dancers perform to “You Can’t Stop The Beat”, a song that views the future with immense optimism for all people. But the song is white-sounding, especially when compared to “Big, Blonde and Beautiful” or “Now Run and Tell That”, both of which are performed by black characters in the movie, and both of which also have a traditionally black, soulful sound. So, Tracy triumphs in the successful integration of the Corny Collins Show, but Hairspray the movie ultimately enforces the idea that the white way is the right way.