The Twilight saga is a story with many threads. It tells the story of a love triangle between Bella Swan, a vampire named Edward Cullen, and a werewolf named Jacob Black. It tells a story of gender roles, as decisions about Bella’s well-being are often made by Edward and Jacob; not by her. It weaves together threads about abstinence, as Edward is afraid of having sex with Bella because if he doesn’t show restraint he could kill her. The saga even tells a story about Mormonism.

Operating in a manner that is sometimes more covert and often more insidious than these stories, however, is one about race. In “White,” Richard Dyer asserts that racial images pervade popular culture, even, or especially, where race seems unimportant. If Dyer’s argument is to be believed, then even though Twilight is not explicitly about race, it still tells a racial story and adjusts our attitudes towards it.

To assess Dyer’s claim, let’s examine how race is represented in three character types in the Twilight films: humans, vampires, and werewolves.

Cover art for Twilight

Humans

Twilight makes it hard not to be conscious of skin color from the opening minutes. As soon as Bella starts high school in Forks, Washington, she is subjected to the romantic and sexual advances of several boys. The advances made by these boys differ in tactics and in the response generated, and these differences parallel racial differences in the characters who make them.

A white character, Mike Newton, is always nervous around Bella and constantly fumbles over his words when he talks to her. Most of the time, when he gets the nerve to, say, ask Bella to prom, she simply blows him off. The one time she does accept his offer to go to a movie (on the condition that their friends can also come), Mike gets sick because the movie was too gory. With Mike gone, Jacob takes the opportunity to be forward about his feelings for Bella. It’s hard not to feel sorry for Mike in this case. He didn’t do anything wrong. The poor kid just lost his chance to get his girl.

The films picture different tactics that elicit different responses when a black student, Tyler Crowley hits on Bella. In one scene, Tyler runs up behind Bella at lunch and kisses her on the cheek; Bella responds with unmistakable annoyance. Tyler doesn’t ask her if she would like to be kissed, and he doesn’t seem phased by her annoyance. This kiss, between a black male and a white female, was sexual harassment.

Bella is visibly annoyed when Tyler kisses her on the cheek

Besides Tyler, the only other named black human in the saga is a man named J. Jenks, who makes fake IDs and passports. Black humans in Twilight commit crimes. One role of white humans in the series, then, is to hold black humans accountable for their actions. Bella’s father, Charlie, is a cop; it’s his job to arrest people like J. Jenks. And when Tyler kisses Bella on the cheek, Mike Newton is the one to chase him away.

Vampires

The vampires in the Twilight films are noted as having skin like porcelain or alabaster. An overwhelming majority of the vampires prior to Breaking Dawn are played by Caucasian actor. One exception is Laurent, who is played by a black actor (Edi Gathegi); however, Gategi wears makeup to lighten his natural skin tone. It seems that the act of being made into a vampire confers a special paleness or whiteness. This notion is strengthened by the color symbolism prevalent in the films: vampires are represented by white. Breaking Dawn extensively uses white and red to represent vampires and humans, respectively. When Bella is turned to a vampire in part one, the film shows her red blood vessels crystalizing and becoming white. Part two opens with several scenes that juxtapose white and red, like the dawn on a snowy mountain top. Vampires are extensively associated with whiteness in the films.

According to Dyer, white people are depicted as pure and god-like, and as transcending the body. He also notes that whiteness is fraught with paradoxes. If Dyer is correct, then we should be able to see these observations come to fruition in the Twilight films.

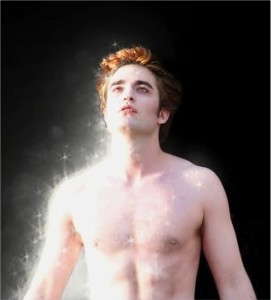

Vampires are often associated with god- or Christ-like qualities in the films. In the sunlight, their skin shimmers and sparkles. In the texts, Bella uses the word “angelic” to describe Edward when he shows her this (Wilson); Bella’s reaction in the film appears to capture the same awe Meyer describes in the books. Some vampires add to the Christ-like metaphor by resisting the temptation to feed on humans by instead feeding on animals. Edward’s father Carlisle even has the discipline to be a doctor, constantly tempted by human blood. In a similar manner, Jesus was constantly tempted to sin, but through immense discipline was able to avoid doing so. Furthermore, Edward and Bella never do more than kiss before they marry, in part because Edward doesn’t want to test his restraint and risk killing Bella, but also because he has somewhat traditional (read: Christian) morals, which champion abstinence. Christian morals are seen elsewhere in the series: in Breaking Dawn, Rosalie encourages Bella not to try and terminate her pregnancy despite the fact that it may kill her; she’s staunchly pro-life, a stance which has been associated with Christians by modern popular culture. There is a clear association between vampires, especially the Cullens, and Christianity and purity. Vampires also often transcend the body using special abilities. Edward can read others’ minds, and so his being extends to the minds of others. Alice can see the future, and so her awareness transcends time itself.

Edward’s skin shimmers in the sunlight

Dyer notes that whiteness is also paradoxical. As a color, whiteness is both the combination and the absence of all colors. The manifestation of this principle in race is messy and varied, allowing whiteness to appear pervasive and attainable for all. One example of paradox has already been explored: how can one be granted the ability to transcend the body by their skin color, a characteristic of the very body they transcend? There are other examples of paradox in Twilight; for example, despite their strong association with whiteness, vampires (unlike all other species in the series) can be doubly associated with blackness. This distinction serves to demarcate the good vampires (those like the Cullens who feed on animals) and bad vampires (those who feed on humans). While the Cullens and other “good” vampires are extensively associated with white, other vampires that feed on humans and are otherwise coded as bad are associated with blackness. The Volturi are one group of vampires that are associated to blackness in addition to whiteness. One way that blackness is coded into the Volturi is that they all wear black robes. Such blackness carries connotations of evil and corruption: the Volturi are depicted as the corrupt oligarchs of vampire-kind, who act in their own interests, and also feed on humans. In Breaking Dawn, they attempt to destroy the Cullen coven for having a half-vampire, half-human child. They justify their politics using a rhetoric of fear: humans for the first time have weapons capable of destroying vampires, so it is more important than ever to keep secret. Anything that produces uncertainty, then, must be destroyed.

The story of Laurent, the black vampire, adds to the vampires’ sense of paradox. Laurent is a friend to the Cullens: he travels to Forks in New Moon to warn them that one of the vampires in his own coven is coming to kill Bella. Despite his occasional goodness, Laurent also does things that are contrary to the characteristics that the saga idealizes in the Cullens. In addition to feeding on humans, Laurent is impulsive (in contrast to the restraint shown by vampires who feed on animals). In New Moon, he crosses Bella in the wilderness and after telling her of Victoria’s plan to kill her, he said he couldn’t resist the urge to do it himself. This led intervention by a werewolf, who killed Laurent. Later, at Bella and Edward’s wedding, one animal-feeding vampire tells Edward that “(Laurent) wanted to be like us.” Laurent, it seems, envied the restraint, the likeness to Christ, the whiteness embodied by the Cullens.

The effect of the double-association granted to vampires like the Volturi is that, while they are unmistakably associated with whiteness, they are not strictly confined to it. As such, the actions of one vampire can hardly be made to represent all vampires – if a vampire does evil, that’s blackness; not all vampires are like that. Other characters, like the werewolves, are not afforded such flexibility.

Werewolves

If whiteness represents likeness to Christ, transcending the body, and paradox, we expect the opposite to be true for blackness in Dyer’s model.

Sure enough, these associations with blackness are seen in the case of the werewolves. Werewolves are the natural enemies of vampires, and so there is plenty of juxtaposition between the two groups in the films. On the whole, the werewolves are thoroughly associated with darkness. They are without exception Quileute Indians, having copper skin and dark features. Sam Uley becomes a jet black werewolf, and Jacob’s last name is even Black.

With the associations between werewolves and darkness in mind, let’s examine how the associations with whiteness seen in the vampires are flipped for werewolves. In vampires, likeness to Christ equates to Christian morals and restraint, and werewolves possess neither of these things. Melissa Burkley points out in Psychology Today that Sam Uley (whose wolf form is jet black, furthering his association with blackness) is an especially immoral character. After learning of Bella’s pregnancy in Breaking Dawn, Sam decides that Bella and her unborn child must be killed for no other reason than that he doesn’t know what to expect from a half-vampire child. Note that Sam has the same response as the Volturi, who are characterized by the double association with white and black. Sam’s immorality is furthered by his history of domestic abuse. His wife, Emily, has a scarred face from one instance when he was angered and struck her (presumably in werewolf form). This particular instance of immorality also begins to illustrate the werewolves’ lack of restraint. Of course Sam didn’t intend to permanently scar his wife; he got upset and it just happened. Impulsivity in werewolves extends beyond Sam: it is inextricably linked to their nature. When Quileutes first transform into werewolves (usually in their late teens), they act erratically and sometimes lose control of their own actions. Just before Jake transforms for the first time, he nearly starts a fight with Mike Newton for no reason in particular. Werewolves, in their darkness, are immoral and impulsive.

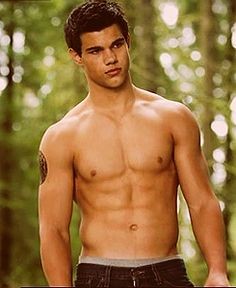

Furthermore, the films place a heavy emphasis on the bodies of the Quileutes. Bella greets Jacob in the beginning of New Moon: “Hey, muscles. You know, anabolic steroids are really bad for you.” Bella makes the viewer acutely aware of Jacob’s very muscular build, and the film builds on this by taking every opportunity to depict Jacob and the other young Quileutes with their shirts off. So the Quileutes’ bodies are sexualized in a way that the vampires’ bodies are not. Even though the Quileutes are shapeshifters and can literally escape their bodies, the films make an impressive effort to tie their identities to their bodies in the minds of the viewers. Ironically, vampires cannot escape their bodies in the same way as the Quileutes, but the films still lead the viewer to associate them with transcending the body.

Jacob’s body is often put on display for the viewers

___

While Twilight is not about race, it is still inundated with racial undertones. The racial story told by the saga associates whiteness and blackness with the characteristics Richard Dyer proposes in “White.” Given this, it is evident that race and racial associations are at play even in places where we wouldn’t expect to find them.

Sources:

Wilson, Natalie. “Got Vampire Privilege?: The Whiteness of Twilight.” SeducedByTwilight. WordPress, 2010.

Burkley, Melissa, PhD. “Is Twilight Prejudiced?: Is Racism a Major Theme in Twilight?” Psychology Today (2011).