Elvira here. We recent graduates lost access to the Williams network in late June! Many thanks to Lydia for helping me circumvent the problem.

“Please don’t write that in your field notebook,” said Mike, one of the directors of the excavation, to my square supervisor Edward three weeks ago with casual aplomb. My square-mates and I had joined the rest of the team a few minutes earlier to begin a mid-season tour of the open digging areas on site, and Edward had just indicated what he and I were certain to be the curved wall in our square. Unbeknownst to the two of us, Mike hadn’t yet been consulted for his opinion on the relationship of this wall to the one we believed was its continuation in the square immediately south of ours. This director thought instead that our wall is positioned at a wide angle to the other and may be unrelated to it. He in any case invited us to exercise more caution before drawing a conclusion like the one Edward had shared.

How appropriate that, not long after posting about the benefit and even the necessity of desire to archaeology, I’d receive a striking reminder of the risk this feeling likewise carries. Mike highlighted not only the possibility that my square’s wall doesn’t join nearby features to form a monumental structure, but also the possibility that the wall’s very curvature is an illusion. Though I’d come to think of this curvature as self-evident, the blocks that would be most necessary to the curve’s articulation are in fact missing.

My little anecdote does something other than remind me, too. It illustrates the reality of what I described in my last post as the due rigor of good archeological inquiry. The engaged form of disagreement I witnessed among my directors is a messy, but integral part of this reality, a part often misrepresented in the scholarly literature where archaeological research is published. In this literature, the arguments of scholars with whom an author disagrees tend to be presented as mere foils for his conclusions rather than as shapers of the thinking that led to those conclusions.

For a student like me, whose basic form of intellectual engagement during the school year is the reading and discussion of precisely such writing, it’s been an immense pleasure to participate in something both as mentally absorbing and as experientially vivid as the dig at Omrit. It’s been no less of a pleasure to contextualize my work on the dig with visits to additional centers of historical significance around Israel. Below is a (mostly lighthearted) selection of photos from the team’s excursions during the last ten days of the season: the Biblical city of Hazor, the largest archaeological site in northern Israel, on June 23; the Herodian harbor and civic complex at Caesarea Maritima on June 24; the fortress and palace at Masada, also Herodian, on June 29; and Jerusalem on June 30. I’m deeply grateful to all the students, teachers, and others who made my time in this country unforgettable not once, but twice.

A view of the unexcavated part of the lower city of Hazor from an Iron Age defense tower at the edge of the upper city. I couldn’t resist the temptation to include a panoramic shot.

Team members entering the fortified upper city of Hazor through an Iron Age gate. The pavilion in the background protects a roughly contemporary administrative complex.

Members of the Williams crew in what survives of Herod the Great’s waterfront palace at Caesarea, with the modern resort town in the background. The brilliant blue belongs not only to the sky, of course, but also to the Mediterranean, that fundamental nurturer of the civilizations on which sites like Omrit shed light. From left to right, Elvira, Lydia, Prof. Rubin, Sharona, and Emily.

A candid shot of our digging companions from Carthage College in front of the Herodian hippodrome at Caesarea.

Lydia wearing a gelato-induced grin at the end of the team’s tour of Caesarea. Espresso, is that the flavor?

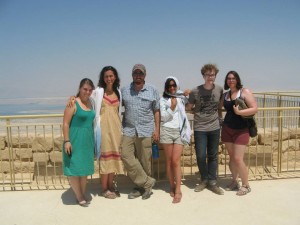

The majority of the Williams crew by the steps to the most spectacular part of Herod the Great’s palace at Masada, the mountaintop that was also the final refuge of Jews revolting against their Roman conquerors in the first century. From left to right, Sam, Sharona, Emily, Prof. Rubin, Lydia, and Elvira.

The same Ephs in what may have been a banquet hall of the Herodian palace at Masada, with the breathtakingly still Dead Sea in the background. Our smiles are stoic—the steps to these ruins are vertiginous, and the sun was merciless on the day of our visit.

From left to right, Amy, Lydia, and Elvira about to enter Jerusalem’s Old City through the sixteenth-century Damascus Gate. I confess that our childish excitement is as much for the bakery we’re about to hunt down as for the city’s monumental marvels.

Mission accomplished in the Old City! Williams students at Zalatimo, the unmarked shop where the eponymous family bakes an Arab pastry called mutabbaq (“folded” in Arabic) from a 150-year-old recipe. Connor and Amy are masking their eagerness to dig into the sugar-drenched layers of phyllo, while Elvira already seems nap-bound after a few sips of minty lemonade.

From left to right, Connor, Amy, Elvira, and Lydia in front of the Western Wall of the Old City’s Temple Mount. It’s fitting for the team’s season of sightseeing to have culminated at the most enduringly relevant piece of Herodian architecture in Israel, a structure that continues to be of supreme religious value to millions.